Introduction to Chapter 17

CHAPTER 17

Revolutions of Industrialization

1750–

Explaining the Industrial Revolution

Why Europe?

Why Britain?

The First Industrial Society

The British Aristocracy

The Middle Classes

The Laboring Classes

Social Protest

Europeans in Motion

Variations on a Theme: Industrialization in the United States and Russia

The United States: Industrialization without Socialism

Russia: Industrialization and Revolution

The Industrial Revolution and Latin America in the Nineteenth Century

After Independence in Latin America

Facing the World Economy

Becoming like Europe?

Reflections: History and Horse Races

Zooming In: Ellen Johnston, Factory Worker and Poet

Zooming In: The English Luddites and Machine Breaking

Working with Evidence: Voices of European Socialism

“Industrialization is, I am afraid, going to be a curse for mankind…. God forbid that India should ever take to industrialism after the manner of the West. The economic imperialism of a single tiny island kingdom (England) is today [1928] keeping the world in chains. If an entire nation of 300 millions took to similar economic exploitation, it would strip the world bare like locusts…. Industrialization on a mass scale will necessarily lead to passive or active exploitation of the villagers…. The machine produces much too fast.”1

Such were the views of the famous Indian nationalist and spiritual leader Mahatma Gandhi, who subsequently led his country to independence from British colonial rule by 1947, only to be assassinated a few months later. However, few people anywhere have agreed with the heroic Indian figure’s views on industrialization. Since its beginning in Great Britain in the late eighteenth century, the idea of industrialization, if not always its reality, has been embraced in every kind of society, both for the wealth it generates and for the power it conveys. Even Gandhi’s own country, once it achieved its independence, largely abandoned its founding father’s vision of small-

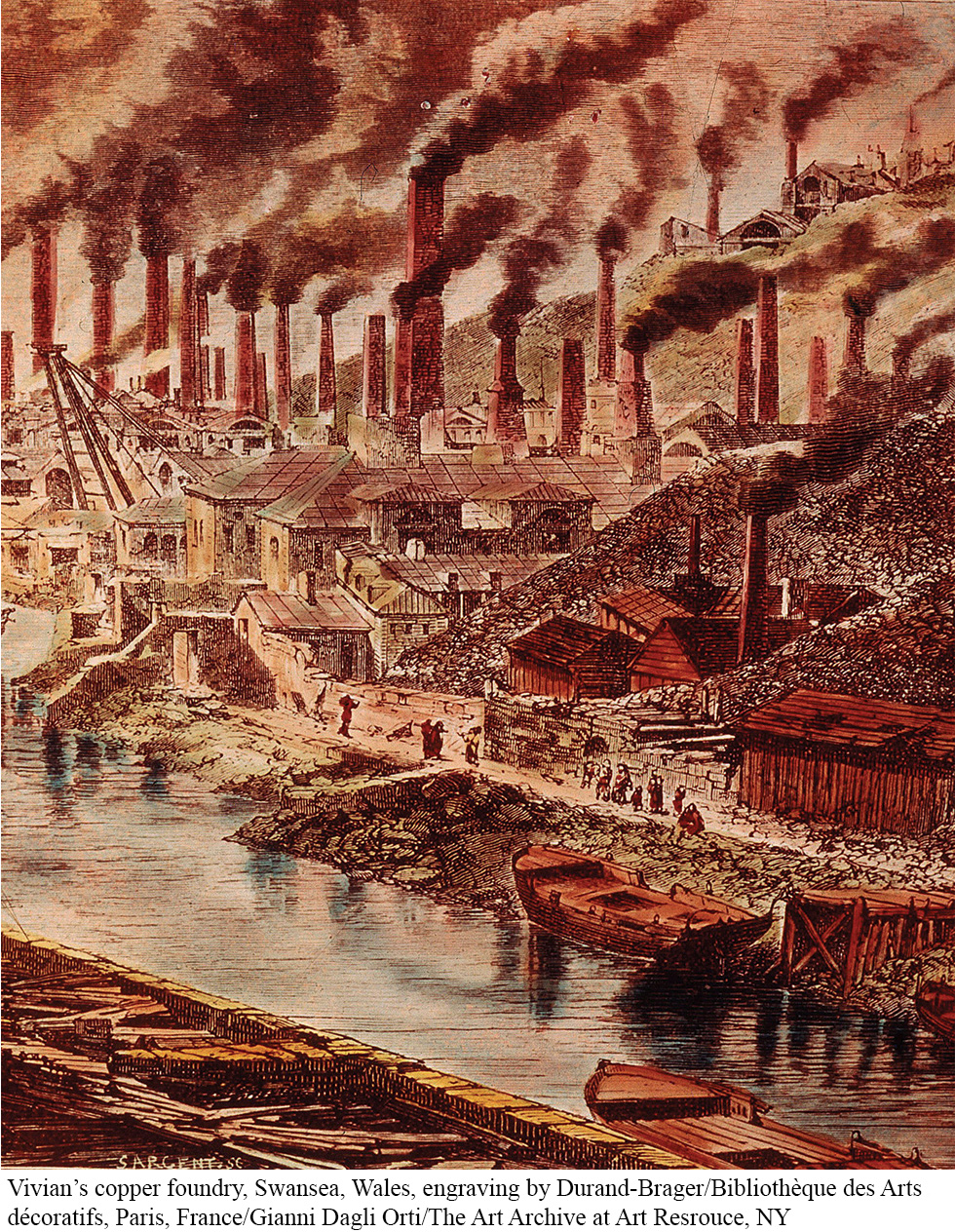

No element of Europe’s modern transformation held a greater significance for the history of humankind than the Industrial Revolution, which took place initially in the century and a half between 1750 and 1900. It drew on the Scientific Revolution and accompanied the unfolding legacy of the French Revolution to utterly transform European society and to propel Europe into a temporary position of global dominance. Not since the breakthrough of the Agricultural Revolution some 12,000 years ago had human ways of life been so fundamentally altered. Also transformed was the human relationship to the natural world as our species learned to access energy resources derived from outside of the biosphere—

In any long-

| A MAP OF TIME | |

|---|---|

| 1712 | Early steam engine in Britain |

| 1780s | Beginning of British Industrial Revolution |

| 1812 | Locomotives first used to haul coal in England |

| 1832 | Reform Bill gives vote to middle- |

| 1848 | Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto |

| 1850s | Beginning of railroad building in Argentina, Cuba, Chile, Brazil |

| 1861 | Freeing of serfs in Russia |

| 1864– |

First International socialist organization in Europe |

| After 1865 | Rapid growth of U.S. industrialization |

| After 1868 | Takeoff of Japanese industrialization |

| 1869 | Opening of transcontinental railroad across United States |

| 1871 | Unification of Germany |

| 1889– |

Second International socialist organization in Europe |

| 1890s | Rapid growth of Russian industrialization |

| 1891– |

Building of trans- |

| 1905 | Failed revolution in Russia |

| 1910– |

Mexican Revolution |

| 1917 | Russian Revolution |

SEEKING THE MAIN POINT

In what ways did the Industrial Revolution mark a sharp break with the past? In what ways did it continue earlier patterns?