Education

For an important minority, it was the acquisition of Western education, obtained through missionary or government schools, that generated a new identity. To many European colonizers, education was a means of “uplifting native races,” a paternalistic obligation of the superior to the inferior. To previously illiterate people, the knowledge of reading and writing of any kind often suggested an almost magical power. Within the colonial setting, it could mean an escape from some of the most onerous obligations of living under European control, such as forced labor. More positively, it meant access to better-paying positions in government bureaucracies, mission organizations, or business firms and to the exciting imported goods that their salaries could buy. Moreover, education often provided social mobility and elite status within their own communities and an opportunity to achieve, or at least approach, equality with whites in racially defined societies. An African man from colonial Kenya described an encounter he had as a boy in 1938 with a relative who was a teacher in a mission school:

Aged about 25, he seems to me like a young god with his smart clothes and shoes, his watch, and a beautiful bicycle. I worshipped in particular his bicycle that day and decided that I must somehow get myself one. As he talked with us, it seemed to me that the secret of his riches came from his education, his knowledge of reading and writing, and that it was essential for me to obtain this power.26

What impact did Western education have on colonial societies?

Many such people ardently embraced European culture, dressing in European clothes, speaking French or English, building European-style houses, getting married in long white dresses, and otherwise emulating European ways. Some of the early Western-educated Bengalis from northeastern India boasted about dreaming in English and deliberately ate beef, to the consternation of their elders. In a well-known poem titled “A Prayer for Peace,” Léopold Senghor, a highly educated West African writer and political leader, enumerated the many crimes of colonialism and yet confessed, “I have a great weakness for France.” Asian and African colonial societies now had a new cultural divide: between the small numbers who had mastered to varying degrees the ways of their rulers and the vast majority who had not. Literate Christians in the East African kingdom of Buganda referred with contempt to their “pagan” neighbors as “those who do not read.”

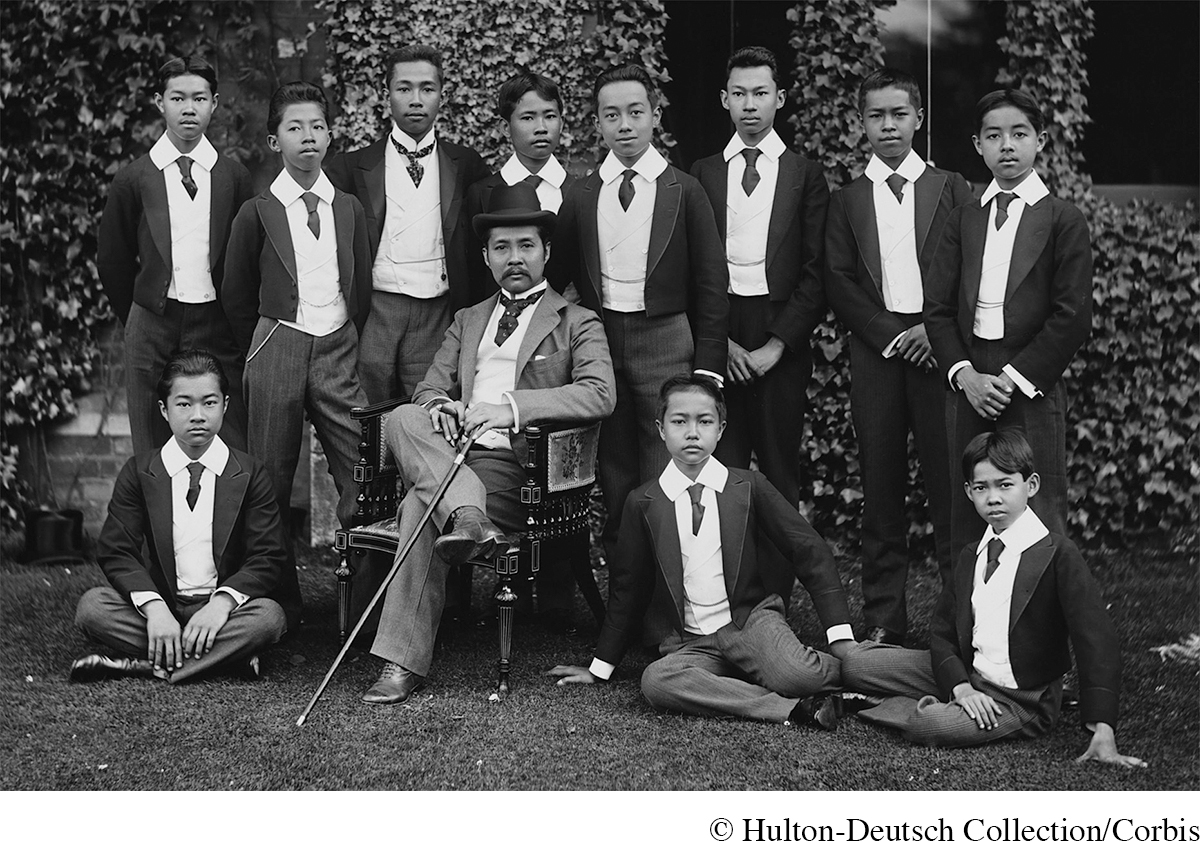

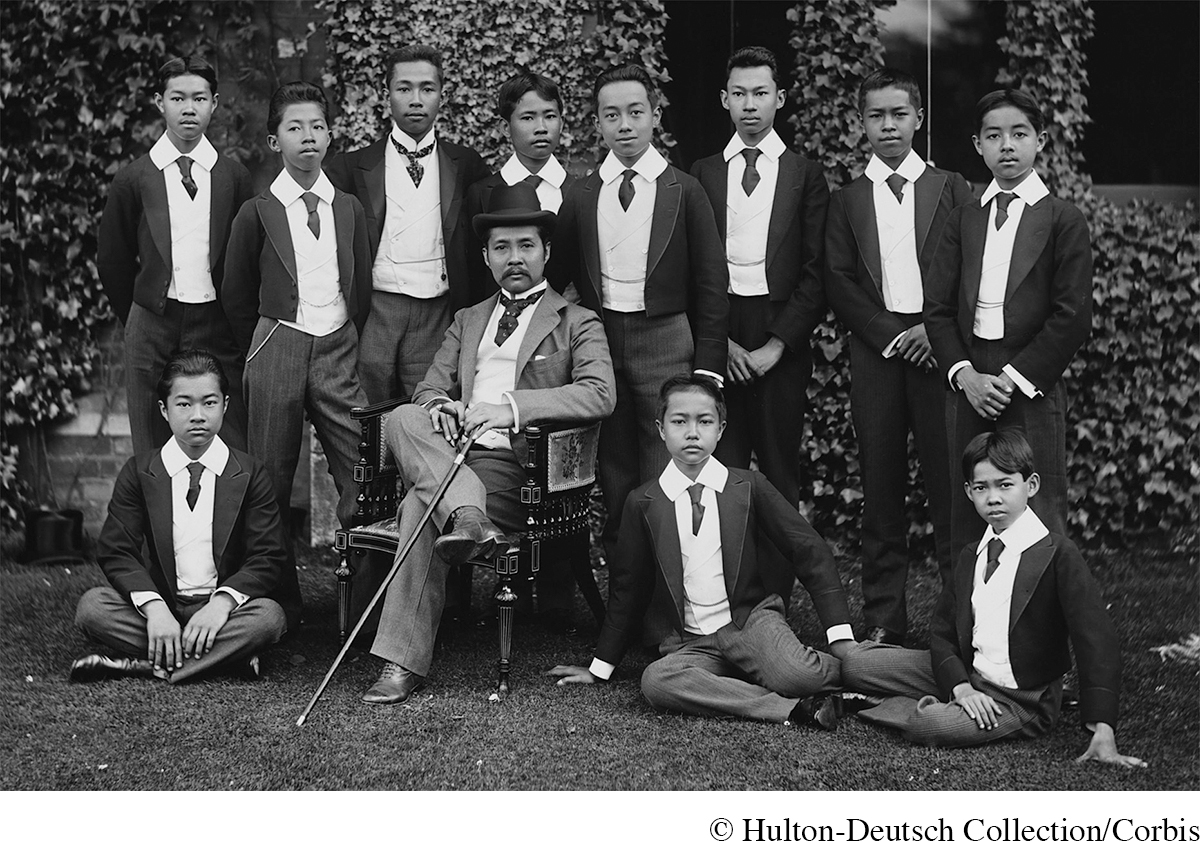

The Educated Elite Throughout the Afro-Asian world of the nineteenth century, the European presence generated a small group of people who enthusiastically embraced the culture and lifestyle of Europe. Here King Chulalongkorn of Siam poses with the crown prince and other young students, all of them impeccably garbed in European clothing. (© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis)

Many among the Western-educated elite saw themselves as a modernizing vanguard, leading the regeneration of their societies in association with colonial authorities. For them, at least initially, the colonial enterprise was full of promise for a better future. The Vietnamese teacher and nationalist Nguyen Thai Hoc, while awaiting execution in 1930 by the French for his revolutionary activities, wrote about his earlier hopes: “At the beginning, I had thought to cooperate with the French in Indochina in order to serve my compatriots, my country, and my people, particularly in the areas of cultural and economic development.”27 Senghor too wrote wistfully about an earlier time when “we could have lived in harmony [with Europeans].”

In nineteenth-century India, Western-educated men organized a variety of reform societies, which drew inspiration from the classic texts of Hinduism while seeking a renewed Indian culture that was free of idolatry, caste restrictions, and other “errors” that had entered Indian life over the centuries. Much of this reform effort centered on improving the status of women. Thus reformers campaigned against sati, the ban on remarriage of widows, female infanticide, and child marriages, while advocating women’s education and property rights. For a time, some of these Indian reformers saw themselves working in tandem with British colonial authorities. One of them, Keshub Chunder Sen (1838–1884), spoke to his fellow Indians in 1877: “You are bound to be loyal to the British government that came to your rescue, as God’s ambassador, when your country was sunk in ignorance and superstition…. India in her present fallen condition seems destined to sit at the feet of England for many long years, to learn western art and science.”28 Such fond hopes for the modernization or renewal of Asian and African societies within a colonial framework would be bitterly disappointed. Europeans generally declined to treat their Asian and African subjects—even those with a Western education—as equal partners in the enterprise of renewal. The frequent denigration of their cultures as primitive, backward, uncivilized, or savage certainly rankled, particularly among the well educated. “My people of Africa,” wrote the West African intellectual James Aggrey in the 1920s, “we were created in the image of God, but men have made us think that we are chickens, and we still think we are; but we are eagles. Stretch forth your wings and fly.”29 In the long run, the educated classes in colonial societies everywhere found European rule far more of an obstacle to their countries’ development than a means of achieving it. Turning decisively against a now-despised foreign imperialism, they led the many struggles for independence that came to fruition in the second half of the twentieth century.