Industry and Empire

Behind much of Europe’s nineteenth-

Change

In what ways did the Industrial Revolution shape the character of nineteenth-

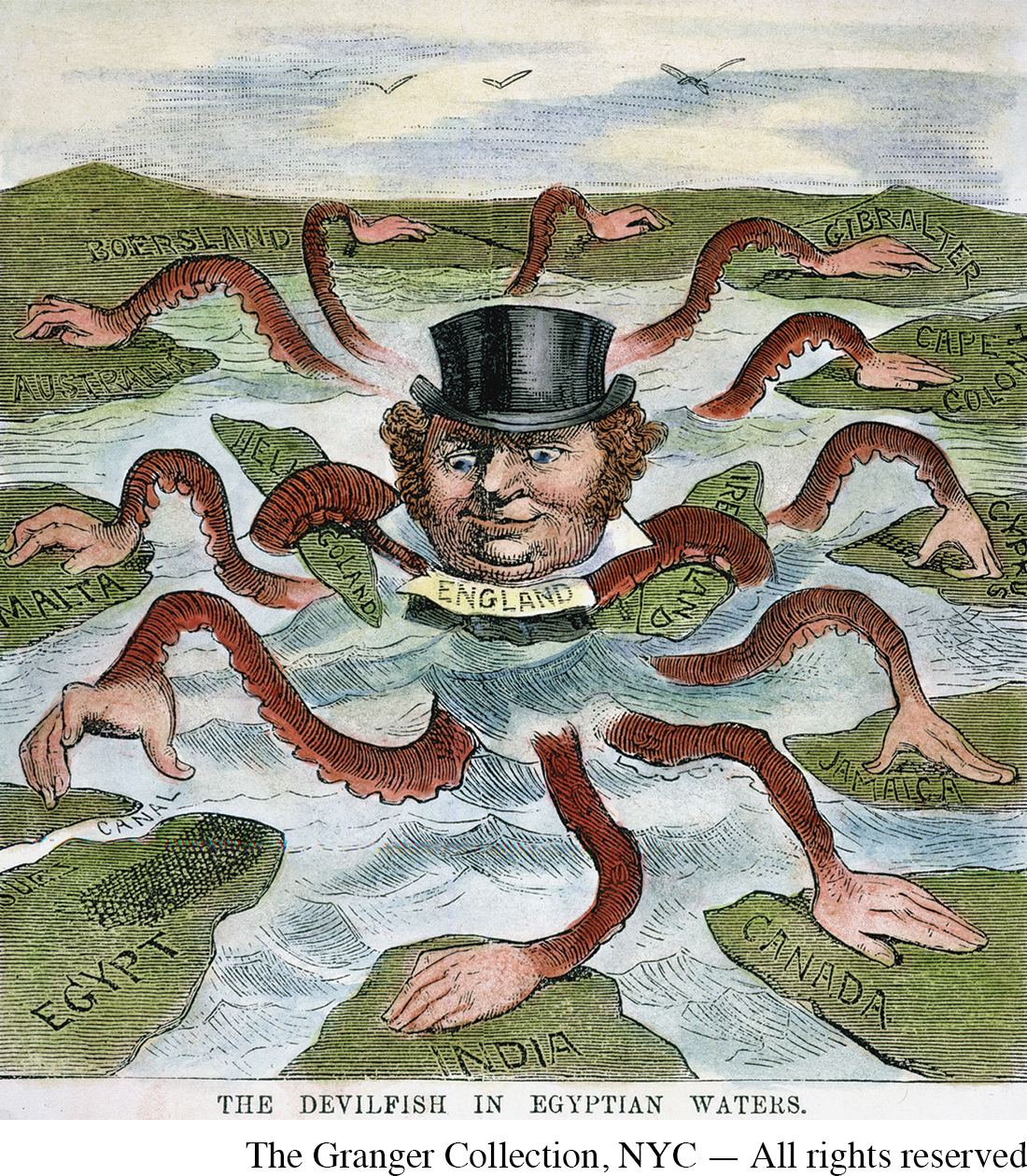

Furthermore, Europe needed to sell its own products. One of the peculiarities of industrial capitalism was that it periodically produced more manufactured goods than its own people could afford to buy. By 1840, for example, Britain was exporting 60 percent of its cotton-

Much the same could be said for capital, for European investors often found it more profitable to invest their money abroad than at home. Between 1910 and 1913, Britain was sending about half of its savings overseas as foreign investment. In 1914, it had some 3.7 billion pounds sterling invested abroad, about equally divided between Europe, North America, and Australia on the one hand and Asia, Africa, and Latin America on the other.

Wealthy Europeans also saw social benefits to foreign markets, which served to keep Europe’s factories humming and its workers employed. The English imperialist Cecil Rhodes confided his fears to a friend in the late nineteenth century:

Yesterday I attended a meeting of the unemployed in London and having listened to the wild speeches which were nothing more than a scream for bread, I returned home convinced more than ever of the importance of imperialism…. In order to save the 40 million inhabitants of the United Kingdom from a murderous civil war, the colonial politicians must open up new areas to absorb the excess population and create new markets for the products of the mines and factories…. The British Empire is a matter of bread and butter. If you wish to avoid civil war, then you must become an imperialist.2

Thus imperialism promised to solve the class conflicts of an industrializing society while avoiding revolution or the serious redistribution of wealth.

But what made imperialism so broadly popular in Europe, especially in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, was the growth of mass nationalism. By 1871, the unification of Italy and Germany made Europe’s already-

If the industrial era made overseas expansion more desirable or even urgent, it also provided new means for achieving those goals. Steam-

Industrialization also occasioned a marked change in the way Europeans perceived themselves and others. In earlier centuries, Europeans had defined others largely in religious terms. “They” were heathen; “we” were Christian. Even as they held on to this sense of religious superiority, Europeans nonetheless adopted many of the ideas and techniques of more advanced societies. They held many aspects of Chinese and Indian civilization in high regard; they freely mixed and mingled with Asian and African elites and often married their women; some even saw more technologically simple peoples as “noble savages.”

Change

What contributed to changing European views of Asians and Africans in the nineteenth century?

With the advent of the industrial age, however, Europeans developed a secular arrogance that fused with or in some cases replaced their notions of religious superiority. They had, after all, unlocked the secrets of nature, created a society of unprecedented wealth, and used both to produce unsurpassed military power. These became the criteria by which Europeans judged both themselves and the rest of the world.

By such standards, it is not surprising that their opinions of other cultures dropped sharply. The Chinese, who had been highly praised in the eighteenth century, were reduced in the nineteenth century to the image of “John Chinaman”—weak, cunning, obstinately conservative, and, in large numbers, a distinct threat, represented by the “yellow peril” in late nineteenth-

Peoples of Pacific Oceania and elsewhere could be regarded as “big children,” who lived “closer to nature” than their civilized counterparts and correspondingly distant from the high culture with which Europeans congratulated themselves. Upon visiting Tahiti in 1768, the French explorer Bougainville concluded: “I thought I was walking in the Garden of Eden.”3 Such views could be mobilized to criticize the artificiality and materialism of modern European life, but they could also serve to justify the conquest of people who were, apparently, doing little to improve what nature had granted them. Writing in 1854, a European settler in Australia declared: “The question comes to this; which has the better right—

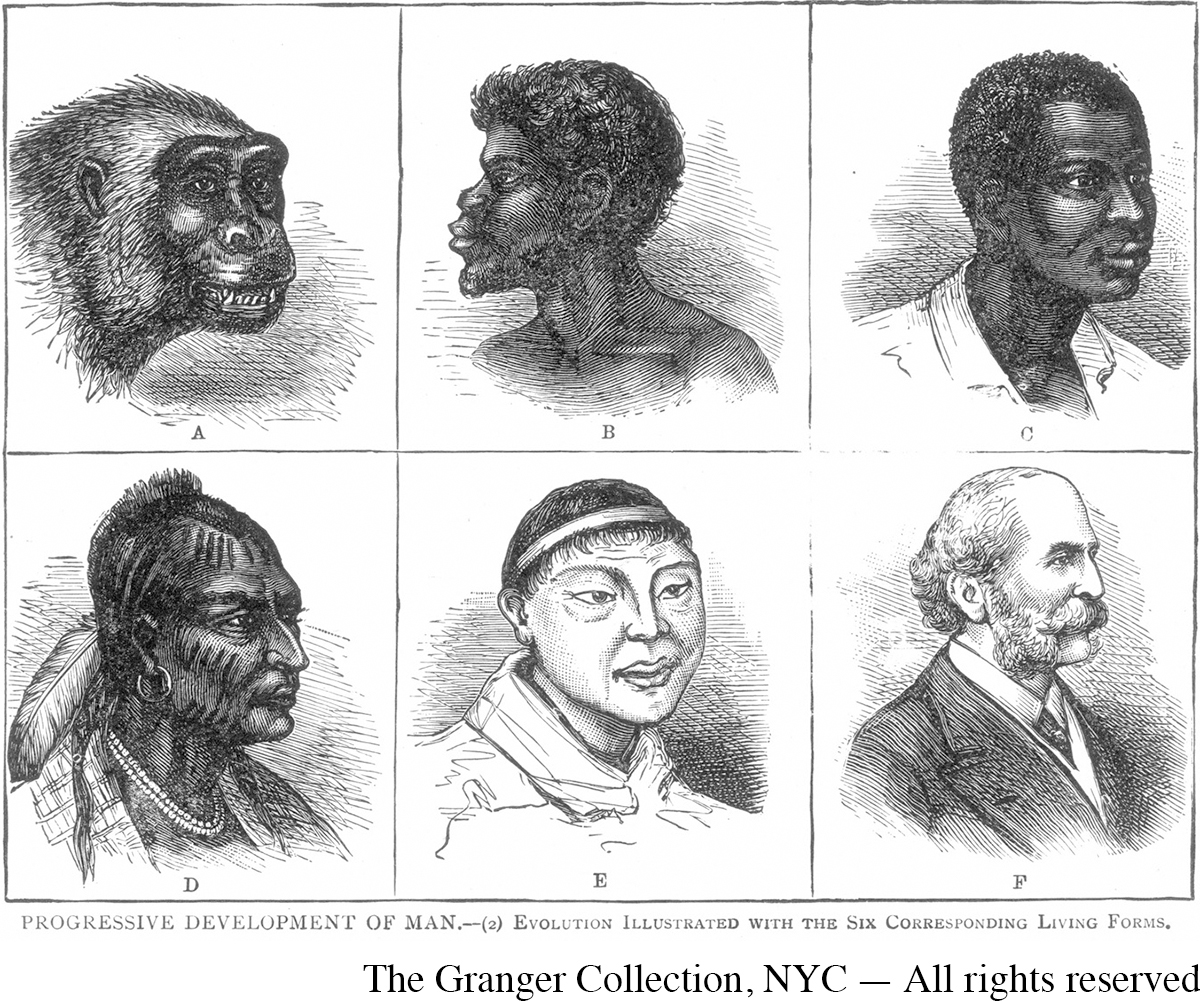

Increasingly, Europeans viewed the culture and achievements of Asian and African peoples through the prism of a new kind of racism, expressed now in terms of modern science. Although physical differences had often been a basis of fear or dislike, in the nineteenth century Europeans increasingly used the prestige and apparatus of science to support their racial preferences and prejudices. Phrenologists, craniologists, and sometimes physicians used allegedly scientific methods and numerous instruments to classify the size and shape of human skulls and concluded, not surprisingly, that those of whites were larger and therefore more advanced. Nineteenth-

These ideas influenced how Europeans viewed their own global expansion. Almost everyone saw it as inevitable, a natural outgrowth of a superior civilization. For many, though, this viewpoint was tempered with a genuine, if condescending, sense of responsibility to the “weaker races” that Europe was fated to dominate. “Superior races have a right, because they have a duty,” declared the French politician Jules Ferry in 1883. “They have the duty to civilize the inferior races.”6 That “civilizing mission” included bringing Christianity to the heathen, good government to disordered lands, work discipline and production for the market to “lazy natives,” a measure of education to the ignorant and illiterate, clothing to the naked, and health care to the sick, all while suppressing “native customs” that ran counter to Western ways of living. In European thinking, this was “progress” and “civilization.”

A harsher side to the ideology of imperialism derived from an effort to apply, or perhaps misapply, the evolutionary thinking of Charles Darwin to an understanding of human societies. The key concept of this “social Darwinism,” though not necessarily shared by Darwin himself, was “the survival of the fittest,” suggesting that European dominance inevitably involved the displacement or destruction of backward peoples or “unfit” races. Referring to native peoples of Australia, a European bishop declared:

Everyone who knows a little about aboriginal races is aware that those races which are of a low type mentally and who are at the same time weak in constitution rapidly die out when their country comes to be occupied by a different race much more rigorous, robust, and pushing than themselves.7

Such views made imperialism, war, and aggression seem both natural and progressive, for they were predicated on the notion that weeding out “weaker” peoples of the world would allow the “stronger” to flourish. These were some of the ideas with which industrializing and increasingly powerful Europeans confronted the peoples of Asia and Africa in the nineteenth century.