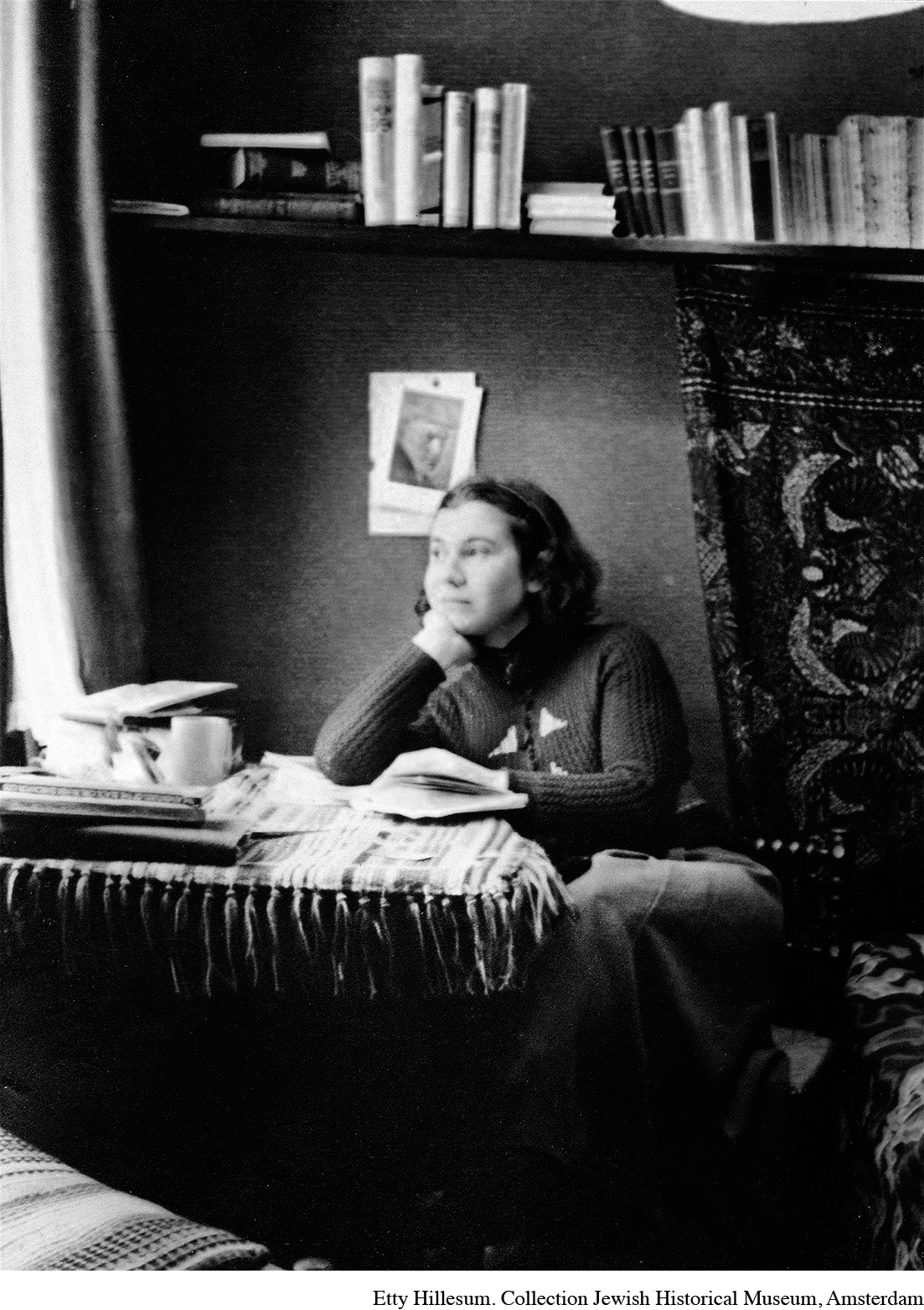

ZOOMING IN: Etty Hillesum, Witness to the Holocaust

Not often can historians penetrate the inner worlds of the people they study. But in the letters and diary of Etty Hillesum, a young Dutch Jewish woman caught up in the Nazi occupation of her country during the early 1940s, we can catch a glimpse of her expanding interior life even as her external circumstances contracted sharply amid the unfolding of the Holocaust.8

Born in 1914, Etty was the daughter of a Dutch academic father and a Russian-

Etty initially reacted to these events with hatred and depression. She wrote, “I am suddenly beside myself with anger, cursing and swearing at the Germans,” and was even upset with a German woman living in her house who had no connections whatever with the Nazis. “They are out to destroy us completely,” she wrote on July 3, 1942. “Today I am filled with despair.” Over time, however, her perspective changed. “I really see no other solution than to turn inward and to root out all the rottenness there.” One day, with the “sound of fire, shooting, bombs” raging outside, Etty listened to a Bach recording and wrote: “I know and share the many sorrows a human being can experience, but I do not cling to them; they pass through me, like life itself, as a broad eternal stream … and life continues…. If you have given sorrow the space that its gentle origins demand, then you may say that life is beautiful and so rich … that it makes you want to believe in God.”

Meanwhile, Etty had fallen deeply in love with her fifty-

Eventually, Etty found herself in Westerbork, a transit camp for Dutch Jews awaiting transport to the east and almost certain death. Friends had offered to hide her, but Etty insisted on voluntarily entering the camp, where she operated as an unofficial social worker and sought to become the “thinking heart of the barracks.” In the camp, panic erupted regularly as new waves of Jews were transported east. Babies screamed as they were awakened to board the trains. “The misery here is really indescribable,” she wrote in mid-

Even there, however, Etty’s emerging inner life found expression. “Late at night …,” she wrote, “I often walk with a spring in my step along the barbed wire. And then time and again, it soars straight from my heart … the feeling that life is glorious and magnificent and that one day we shall be building a whole new world. Against every new outrage and every fresh horror, we shall put up one more piece of love and goodness, drawing strength from within ourselves. We may suffer, but we must not succumb.”

Etty’s transport came on September 7, 1943, when she, her parents, and a brother boarded a train for Auschwitz. Her parents were gassed immediately upon arrival, and Etty followed on November 30. Her last known writing was a postcard tossed from the train as it departed Westerbork. It read in part: “I am sitting on my rucksack in the middle of a full freight car. Father, mother, and Mischa [her brother] are a few cars behind…. We left the camp singing.”

Etty Hillesum’s public life, like that of most people, left little outward mark on the world she briefly inhabited, except for the small circle of her friends and family. But the record of her inner life, miraculously preserved, remains among the greatest spiritual testaments to emerge from the horrors of the Nazi era, a tribute to the possibilities of human transformation, even amid the most horrendous of circumstances.

Questions: In what ways did Etty experience the Nazi phenomenon? How might you assess Etty’s interior response to the Nazis? Was it a “triumph of the human spirit” or an evasion of the responsibility to resist evil more directly?