ZOOMING IN: Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Muslim Pacifist

Born in 1890 in the Northwest Frontier Province of colonial India, Abdul Ghaffar Khan hailed from a well-

As a boy, Khan attended a British mission school, which he credited with instilling in him a sense of service to his people. He later turned down a chance to enter an elite military unit of the Indian army when he learned that he would be required to defer to British officers junior to him in rank. His mother opposed his own plan to study in an English university, and so he turned instead to the “service of God and humanity.” In practice, this initially meant social reform and educational advancement within Pathan villages, but in the increasingly nationalist environment of early twentieth-

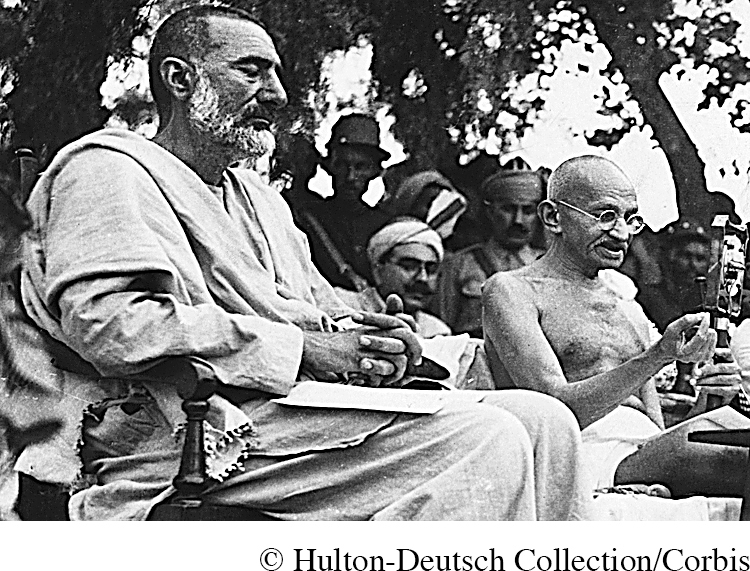

Deeply impressed with Gandhi’s message of nonviolent protest, in 1929 Abdul Khan established the Khudai Khidmatgar, or “Servants of God,” movement in his home region. Committed to nonviolence, social reform, the unity of the Pathan people, and the independence of India, the Khudai Khidmatgar soon became affiliated with the Indian National Congress, led by Gandhi, which was the leading nationalist organization in the country. During the 1930s and early 1940s, Abdul Khan’s movement gained a substantial following in the Frontier Province, becoming the dominant political force in the area. Moreover, it largely adhered to its nonviolent creed in the face of severe British oppression and even massacres. In the process, Abdul Khan acquired a prominent place beside Gandhi in the Congress Party and an almost legendary status in his own Frontier region. His imposing six-

It was a remarkable achievement. Gandhi’s close associate Jawaharlal Nehru later wrote that both he and Gandhi were astonished that “Abdul Gaffar Khan made his turbulent and quarrelsome people accept peaceful methods of political action, involving enormous suffering.”9 In large measure, this had happened because Abdul Khan was able to root nonviolence in both Islam and Pathan culture. In fact, he had come to nonviolence well before meeting Gandhi, seeing it as necessary for overcoming the incessant feuding of his Pathan people. The Prophet Muhammad’s mission, he declared, was “to free the oppressed, to feed the poor, and to clothe the naked.”10 Nonviolent struggle was a form of jihad, or Islamic holy war, and the suffering it generated was a kind of martyrdom. Furthermore, he linked nonviolent struggle to Pathan male virtues of honor, bravery, and strength.

By the mid-

Despite his deep disappointment about partition and the immense violence that accompanied it, Abdul Khan declared his allegiance to Pakistan. But neither he nor his Servants of God followers could gain the trust of the new Pakistani authorities, who refused to recognize their role as freedom fighters in the struggle against colonial rule. His long opposition to the creation of Pakistan made his patriotism suspect; his advocacy of Pathan unity raised fears that he was fostering the secession of that region; and his political liberalism and criticism of Pakistani military governments generated suspicions that he was a communist. Thus he was repeatedly imprisoned in Pakistan and in conditions far worse than he had experienced in British jails. He viewed Pakistan as a British effort at divide and rule, “so that the Hindus and the Muslims might forever be at war and forget that they were brothers.”11

Until his death in 1988 at the age of ninety-

Questions: Why do you think Abdul Khan is generally unknown? Where does he fit in the larger history of the twentieth century?