ZOOMING IN: Mozambique: Civil War and Reconciliation

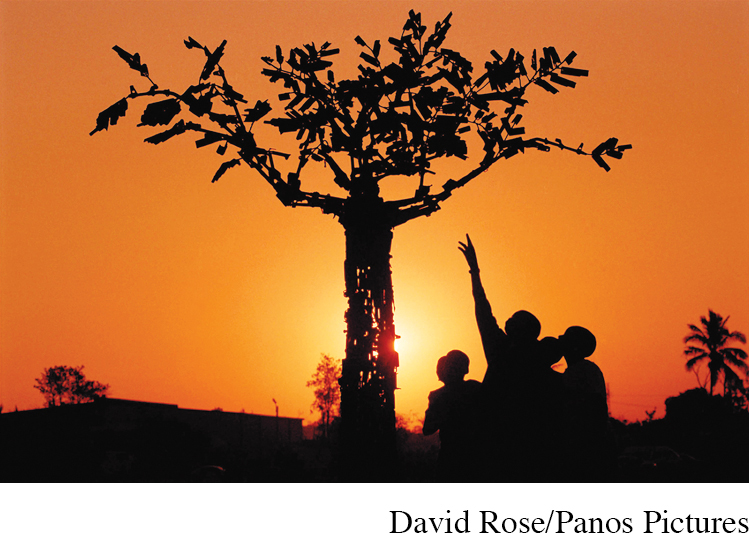

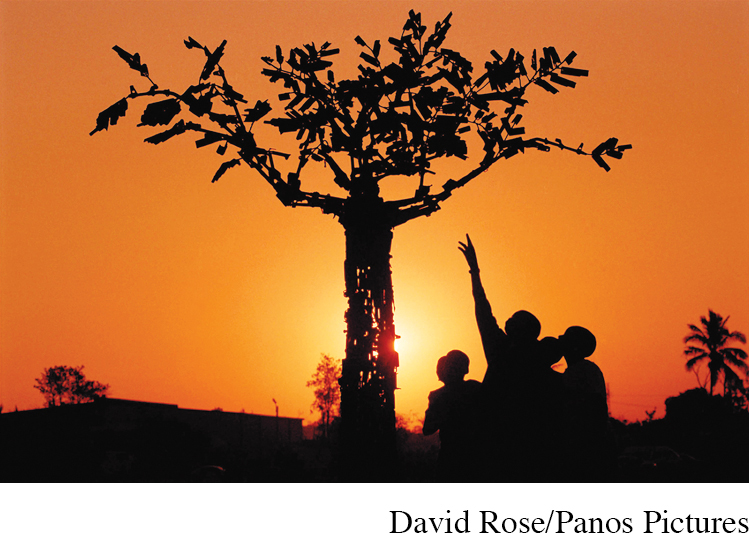

The Tree of Life in Mozambique in 2005. photo: David Rose/Panos Pictures

In the decades after independence, many Asian and African countries experienced bitter civil wars—Nigeria, Rwanda, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, and Burma among others. As their conflicts ended, these countries have faced the issue of reconciliation among former enemies who often hated, despised, and feared one another. Such has been the case in Mozambique, a Portuguese colony in southeastern Africa, which achieved its independence in 1975, after a ten-year armed struggle led by a party called the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO).

Mozambique’s newly independent government, controlled by FRELIMO, came to power in a single-party Marxist-oriented state with strong support from the communist world. Some of its policies—a socialist agenda, dismissal of many traditional chiefs, imprisonment of opponents in “reeducation” camps, forced resettlement of scattered farmers in communal villages—soon antagonized many people. Opposition came together as the Mozambique National Resistance (RENAMO) and found support from the threatened white-ruled regimes in neighboring Rhodesia and South Africa. As weapons from many sources flowed into the country, a terrible civil war erupted in 1977, lasting fifteen years. Altogether, 1 million or more people were killed and another 5 million were displaced, accounting for nearly half the country’s population. On both sides, it was a brutal conflict, with RENAMO especially employing systematic mass killings, rape, and mutilation as a tactic of war. By the end of the 1980s, the military stalemate in Mozambique, coupled with the collapse of white rule in southern Africa and the abandonment of communism in the Soviet Union and China, provided conditions for negotiations, an end to the fighting, and finally a new constitution. In the early 1990s, Mozambique emerged as a democratic, multiparty, market-oriented democracy, and since then the nation has held regular elections every five years.

RENAMO supporters have participated in those elections, and some of their fighters have been integrated into Mozambique’s military forces. But the Mozambican government has not initiated any large-scale process to deal with the enormous abuse and trauma that so many people experienced. State authorities authorized a general amnesty for all crimes committed during the civil war, but they expressed no official recognition of the suffering involved or compassion for the victims. Nothing similar to South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission emerged in Mozambique. The government, Christian churches, and local chiefs alike urged forgiveness without revenge, but offered little to deal with the emotional scars and social conflicts that the civil war had generated. It was, critics charged, “reconciliation without truth.” Indirectly, however, by acknowledging the legitimacy of customary institutions and practices, which FRELIMO had earlier tried to destroy, the government made it possible for local initiatives to operate within a traditional setting.

One of these initiatives involved the spirits of dead soldiers, known as gamba, who returned to possess particular individuals. Traditional healers created rituals designed to appease these spirits. Such ceremonies brought alienated people together, reminded them of the violence of the civil war, elicited confessions of wrongdoing, and set appropriate compensations. In these encounters, local people, whose families and communities were often torn apart by the war, found a way to confront the past and to experience some reconciliation within a culturally familiar setting.

Yet another remarkable private initiative of reconciliation with the past involved young people, many of whom had been forced to participate in the civil war as teenagers. In partnership with the Christian Council of Mozambique, they created a “transforming weapons into tools” project, which sought to collect and destroy some of the millions of weapons left over from the civil war. Animated by the biblical “swords into plowshares” notion, this project invited people to exchange their weapons for tools, such as sewing machines, hoes, plows, bicycles, and construction material. Hundreds of thousands of weapons, perhaps millions, were turned in. One village that recovered a very large number of weapons received a tractor in return. The weapons were then taken apart and turned over to Mozambican artists, who fashioned them into remarkable sculptures—chairs, trees, animals, musical instruments, bicycles, human figures, and more.

Among the most memorable of those sculptures was a Tree of Life, some ten feet tall and weighing 1,000 pounds, accompanied by birds and animals, all made from pieces of dismantled weapons. The symbolism of weapons transformed into objects of comfort or inspiration allowed people to confront the past, while evoking some sense of hope and possibility from the tragedy of the civil war. There was irony too in this project. The Tree of Life was commissioned by and displayed in the British Museum, thus returning to Europe some of the weapons that originated in Europe to fuel the civil war in Mozambique.

Questions: What common features do these various reconciliation efforts share, and how do they differ? What possible responses to them can you imagine?