Experiments with Culture: The Role of Islam in Turkey and Iran

Map 22.4 Iran, Turkey, and the Middle East Among the great contrasts of a very diverse Middle East has been between Turkey, the most secular and Western-oriented country of the region, and Iran, home to the most sustained Islamic revolution in the area.

The quest for economic development represented the embrace of an emerging global culture of modernity with its scientific outlook, its technological achievements, and its focus on material values. Developing countries were also exposed to the changing culture of the West, including feminism, rock and rap, sexual permissiveness, consumerism, and democracy. But the peoples of the Global South had inherited cultural patterns from the more distant past as well. A common issue all across the developing world involved the uneasy relationship between these older traditions and the more recent outlooks associated with modernity and the West. How should traditional African “medicine men” relate to modern hospitals? What happens to Confucian-based family values when confronted with the urban and commercial growth of recent Chinese history? Such tensions provided the raw material for a series of cultural experiments in the twentieth century, and nowhere were they more consequential than in the Islamic world. No single answer emerged to the question of how Islam and modernity should relate to each other, but the experiences of Turkey and Iran illustrate two quite different approaches to this fundamental issue (see Map 22.4). (See Working with Evidence: Contending for Islam for more on this topic.)

In what ways did cultural revolutions in Turkey and Iran reflect different understandings of the role of Islam in modern societies?

In the aftermath of World War I, modern Turkey emerged from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire, led by an energetic general, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (ATT-a-turk) (1881–1938), who fought off British, French, Italian, and Greek efforts to dismember what was left of the old empire. Often compared to Peter the Great in Russia (see “ Russians and Empire” in Chapter 13), Atatürk then sought to transform his country into a modern, secular, and national state. Such ambitions were not entirely new, for they built upon the efforts of nineteenth-century Ottoman reformers, who, like Atatürk, greatly admired European Enlightenment thinking and sought to bring its benefits to their country.

To Atatürk and his followers, to become modern meant “to enter European civilization completely.” They believed that this required totally removing Islam from public life and relegating it to the personal and private realm. Atatürk argued, “Islam will be elevated, if it will cease to be a political instrument.” In fact, he sought to broaden access to the religion by translating the Quran into Turkish and issuing the call to prayer in Turkish rather than Arabic.

Atatürk largely ended, however, the direct political role of Islam. The old sultan, or ruler, of the Ottoman Empire, whose position had long been sanctified by Islamic tradition, was deposed as Turkey became a republic. Furthermore, the caliphate, by which Ottoman sultans had claimed leadership of the entire Islamic world, was abolished, although in fact it had atrophied to the point of having almost no real authority outside of Turkey. All Sufi organizations, sacred tombs, and religious schools were closed and outlawed, and a number of religious titles abolished. Islamic courts were likewise dissolved, while secular law codes, modeled on those of Europe, replaced the sharia. In history textbooks, pre-Islamic Turkish culture was celebrated as the foundation for all ancient civilizations. The Arabic script in which the Turkish language had long been written was exchanged for a new Western-style alphabet that made literacy much easier but rendered centuries of Ottoman culture inaccessible to these newly literate people. (See Working with Evidence, Source 22.1, for an example of Atatürk’s thinking.)

The most visible symbols of Atatürk’s revolutionary program occurred in the realm of dress. Turkish men were ordered to abandon the traditional headdress known as the fez and to wear brimmed hats. Atatürk proclaimed:

A civilized, international dress is worthy and appropriate for our nation, and we will wear it. Boots or shoes on our feet, trousers on our legs, shirt and tie, jacket and waistcoat—and of course, to complete these, a cover with a brim on our heads.15

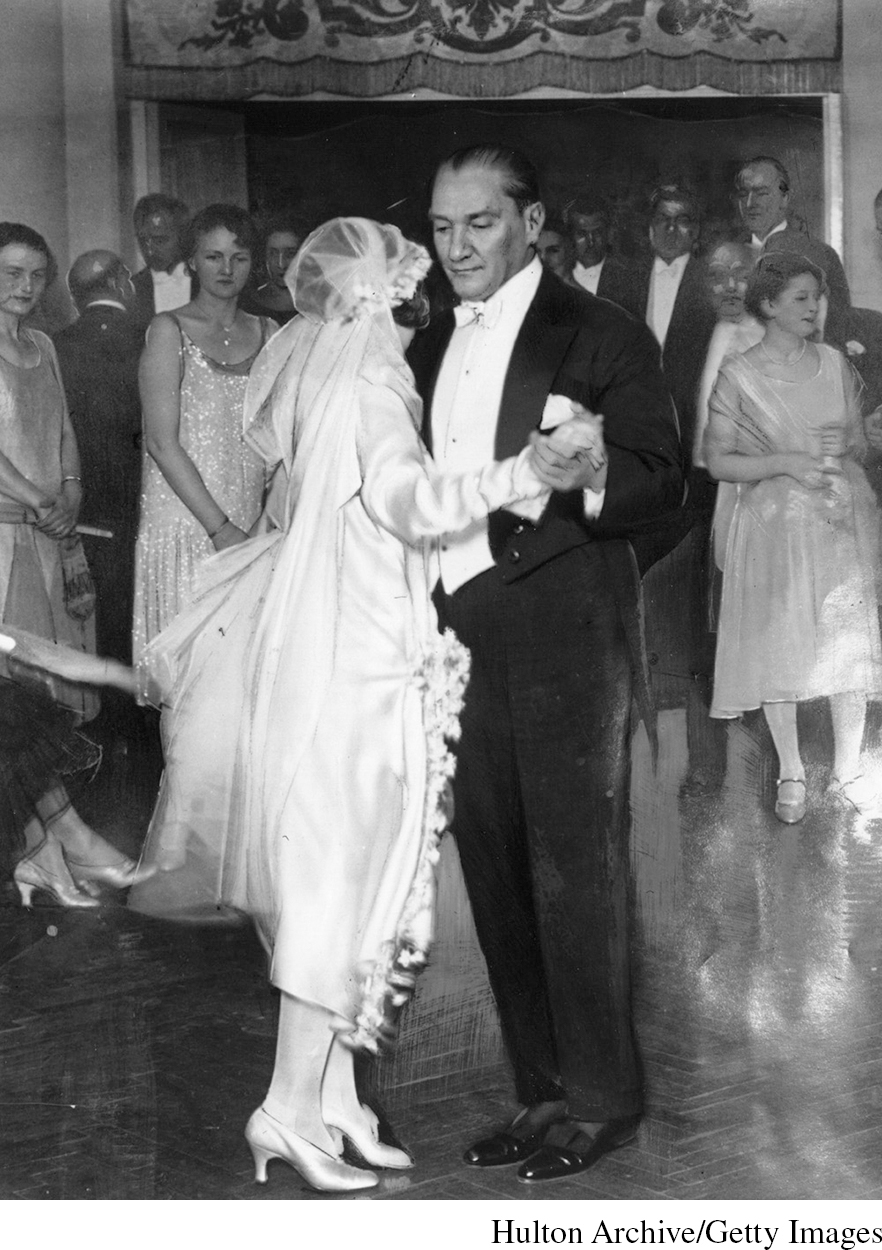

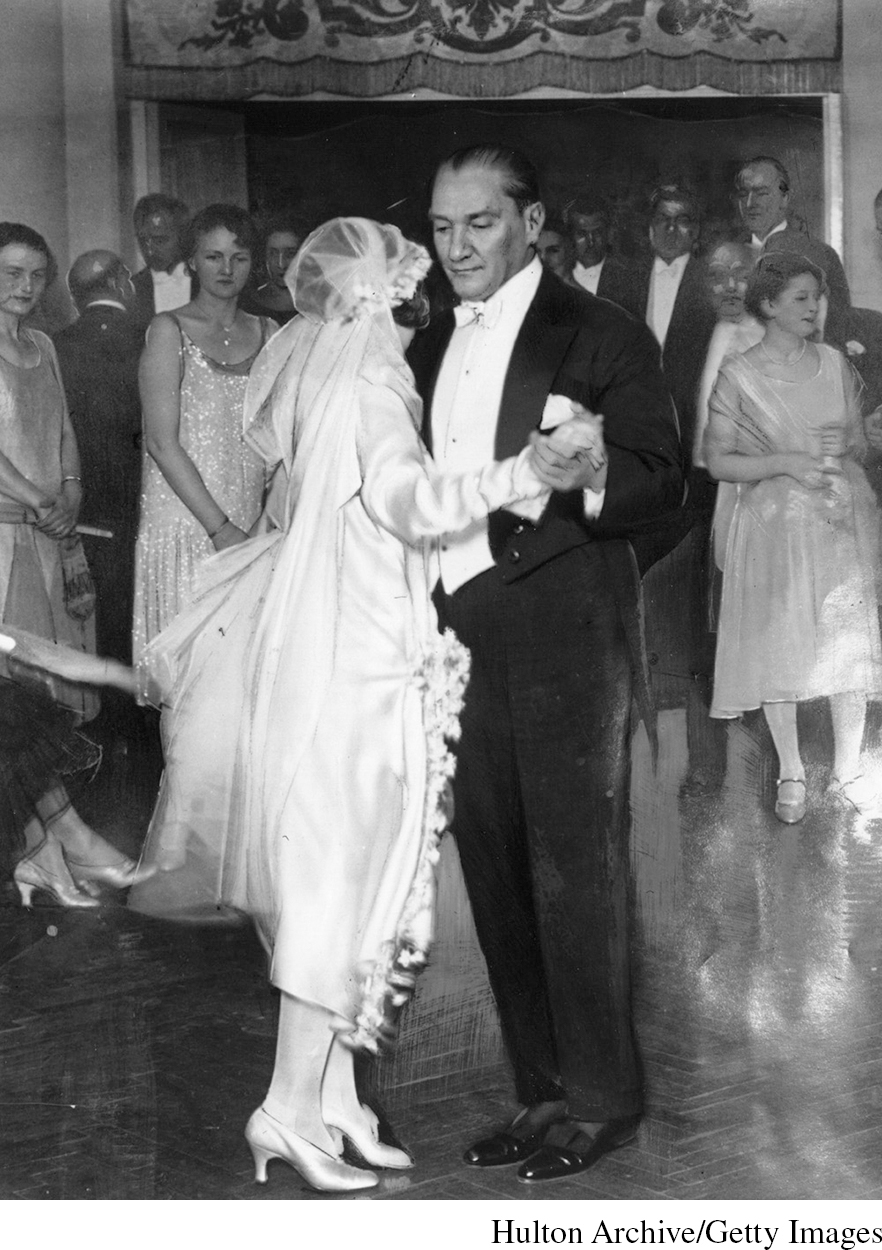

Westernization in Turkey Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of modern Turkey, often appeared in public in elegant European dress, symbolizing for his people a sharp break with traditional Islamic ways of living. Here he is dancing with his adopted daughter at her high-society wedding in 1929. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Although women were not forbidden to wear the veil, many elite women abandoned it and set the tone for feminine fashion in Turkey.

In Atatürk’s view, the emancipation of women was a cornerstone of the new Turkey. In a much-quoted speech, he declared:

If henceforward the women do not share in the social life of the nation, we shall never attain to our full development. We shall remain irremediably backward, incapable of treating on equal terms with the civilizations of the West.16

Thus polygamy was abolished; women were granted equal rights in divorce, inheritance, and child custody; and in 1934 Turkish women gained the right to vote and hold public office, a full decade before French women gained that right. Public beaches were now opened to women as well. As in the early Soviet Union, this was a state-directed feminism, responsive to Atatürk’s views, rather than reflecting popular demands from women themselves.

These reforms represented a “cultural revolution” unique in the Islamic world of the time, and they were imposed against considerable opposition. After Atatürk’s death in 1938, some of them were diluted or rescinded. The call to prayer returned to the traditional Arabic in 1950, and various political groups urged a greater role for Islam in the public arena. Since 2002, a moderate Islamic party has governed the country, while the political role of the military, long the chief defender of Turkish secularism, has diminished. By 2010, an earlier prohibition on women wearing headscarves in universities had largely ended. Nevertheless, the secularism of Atatürk persisted for many Turks and provided a major element in large-scale protests against the government in 2013. But elsewhere in the Islamic world, other solutions to the question of Islam and modernity took shape.

A very different answer emerged in Iran in the final quarter of the twentieth century. That country seemed an unlikely place for an Islamic revolution. Under the government of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (r. 1941–1979), Iran had undertaken what many saw as a quite successful and largely secular modernization effort. The country had great wealth in oil, a powerful military, a well-educated elite, and a solid alliance with the United States. Furthermore, the shah’s so-called White Revolution, intended to promote the country’s modernization, had redistributed land to many of Iran’s impoverished peasants, granted women the right to vote, invested substantially in rural health care and education, initiated a number of industrial projects, and offered workers a share in the profits of those industries. But beneath the surface of apparent success, discontent and resentment were brewing. Traditional small-scale merchants felt threatened by an explosion of imported Western goods and by competition from large businesses. Religious leaders, the ulama, were offended by state control of religious institutions and by secular education programs that bypassed Islamic schools. Educated professionals found Iran’s reliance on the West disturbing. Rural migrants to the country’s growing cities, especially Tehran, faced rising costs and uncertain employment.

A repressive and often-brutal government allowed little outlet for such grievances. Thus opposition to the shah’s regime came to center on the country’s many mosques, where Iran’s Shia religious leaders invoked memories of earlier persecution and martyrdom as they mobilized that opposition and called for the shah’s removal. The emerging leader of that movement was the high-ranking Shia cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini (ko-MAY-nee) (1902–1989), who in 1979 returned from long exile in Paris to great acclaim. By then, massive urban demonstrations, strikes, and defections from the military had eroded support for the shah, who abdicated the throne and left the country.

What followed was also a cultural revolution, but one that moved in precisely the opposite direction from that of Atatürk’s Turkey—toward, rather than away from, the Islamization of public life. The new government defined itself as an Islamic republic, with an elected parliament and a constitution, but in practice conservative Islamic clerics, headed by Khomeini, exercised dominant power. A Council of Guardians, composed of leading legal scholars, was empowered to interpret the constitution, to supervise elections, and to review legislation—all designed to ensure compatibility with a particular vision of Islam. Opposition to the new regime was harshly crushed, with some 1,800 executions in 1981 alone for those regarded as “waging war against God.”17

Khomeini believed that the purpose of government was to apply the law of Allah as expressed in the sharia. Thus all judges now had to be competent in Islamic law, and those lacking that qualification were dismissed. The secular law codes under which the shah’s government had operated were discarded in favor of those based solely on Islamic precedents. Islamization likewise profoundly affected the domain of education and culture. In June 1980, the new government closed some 200 universities and colleges for two years while textbooks, curricula, and faculty were “purified” of un-Islamic influences. Elementary and secondary schools, largely secular under the shah, now gave priority to religious instruction and the teaching of Arabic, even as about 40,000 teachers lost their jobs for lack of sufficient Islamic piety. Pre-Islamic Persian literature and history were now out of favor, while the history of Islam and Iran’s revolution predominated in schools and the mass media. Western loan words were purged from the Farsi language and replaced by their Arabic equivalents.

As in Turkey, the role of women became a touchstone of this Islamic cultural revolution. By 1983, all women were required to wear the modest head-to-toe covering known as hijab, a regulation enforced by roving groups of militants, or “revolutionary guards.” Those found with “bad hijab” were subject to harassment and sometimes lashings or imprisonment. Sexual segregation was imposed in schools, parks, beaches, and public transportation. The legal age of marriage for girls, set at eighteen under the shah, was reduced to nine with parental consent and thirteen, later raised to fifteen, without it. Married women could no longer file for divorce or attend school. Yet, despite such restrictions, many women supported the revolution and over the next several decades found far greater opportunities for employment and higher education than before. By the early twenty-first century, almost 60 percent of university students were women. And women’s right to vote remained intact.

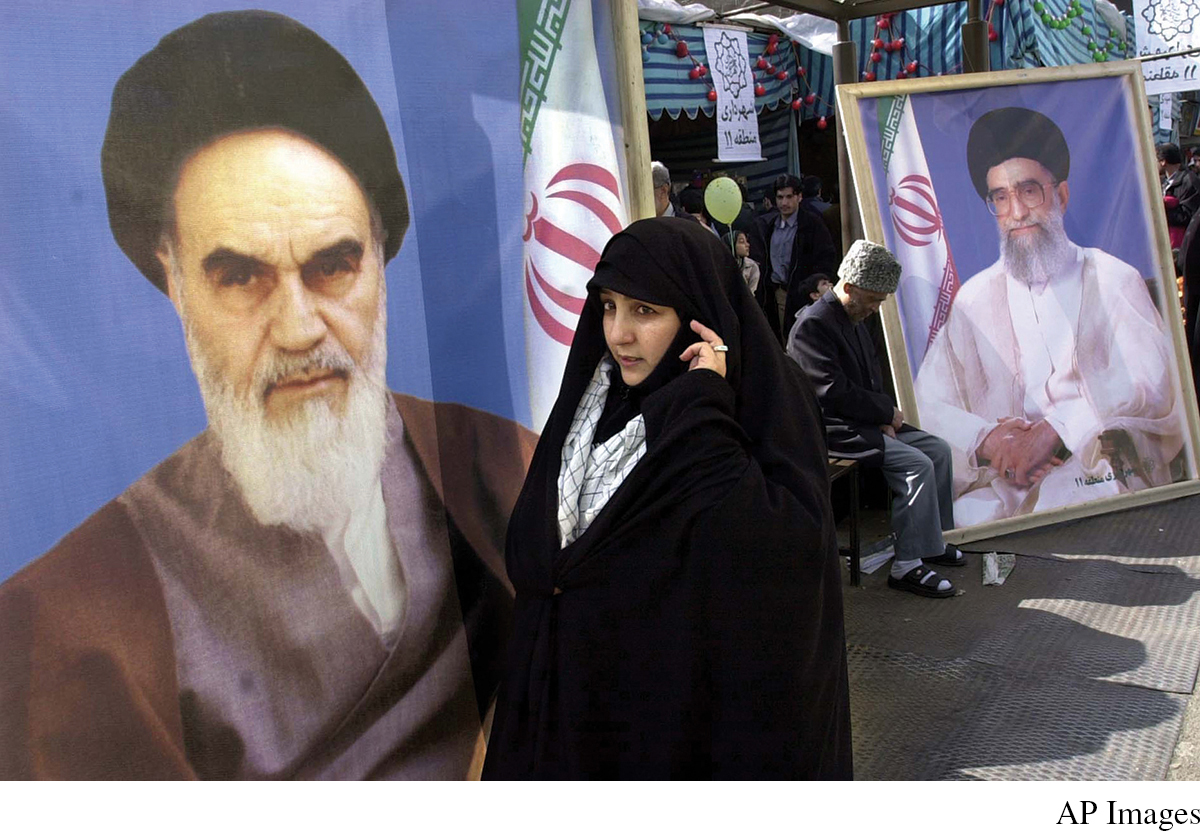

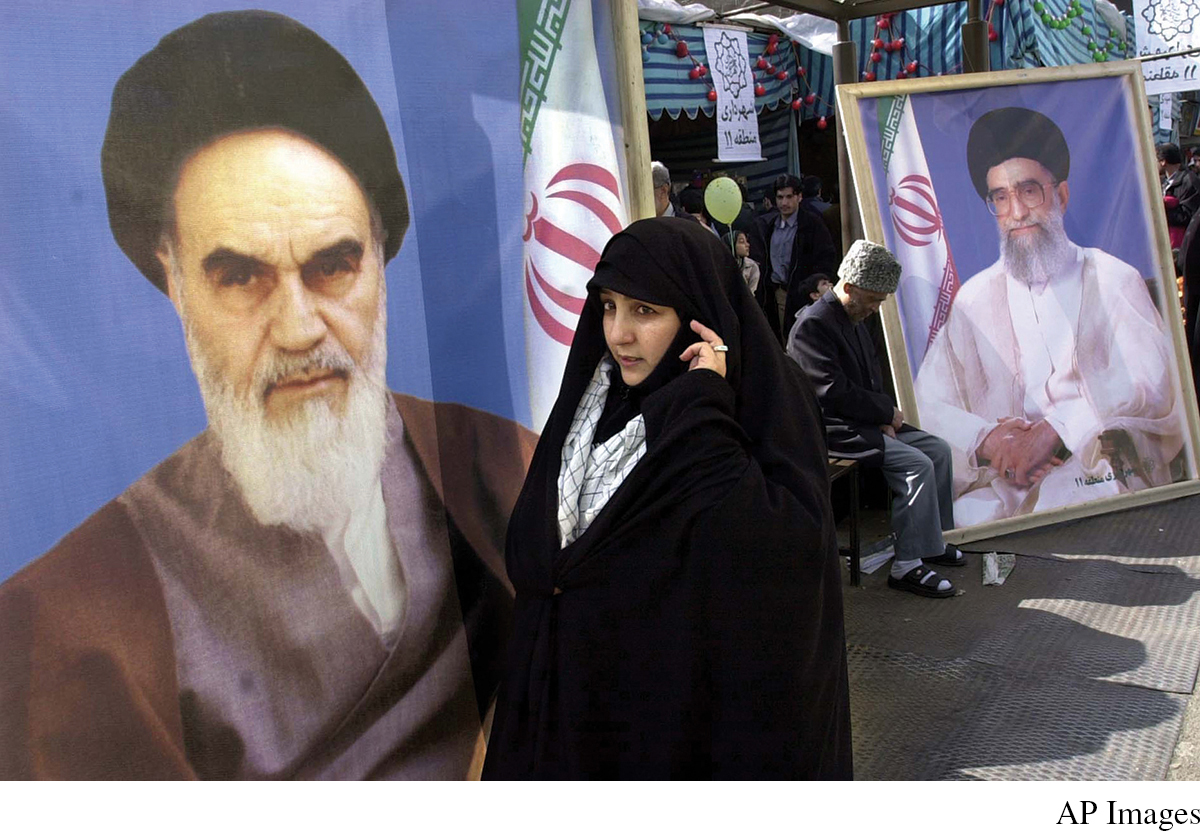

Women and the Iranian Revolution One of the goals of Iran’s Islamic revolution was to enforce a more modest and traditional dress code for the country’s women. In this photo from 2004, a woman clad in a chador and talking on her cell phone walks past a poster of Ayatollah Khomeini, who led that revolution in 1979. (AP Images)

While Atatürk’s cultural revolution of westernization and secularism was largely an internal affair with little interest in extending the Turkish model abroad, Khomeini clearly sought to export Iran’s Islamic revolution. He openly called for the replacement of insufficiently Islamic regimes in the Middle East and offered training and support for their opponents. In Lebanon, Syria, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and elsewhere, Khomeini appealed to Shia minorities and other disaffected people, and Iran became a model to which many Islamic radicals looked. An eight-year war with Saddam Hussein’s highly secularized Iraq (1980–1988) was one of the outcomes and generated enormous casualties. That conflict reflected the differences between Arabs and Persians, between Sunni and Shia versions of Islam, and between a secular Iraqi regime and Khomeini’s revolutionary Islamic government.

After Khomeini’s death in 1989, some elements of this revolution eased a bit. For a time, enforcement of women’s dress code was not so stringent, and a more moderate government came to power in 1997, raising hopes for a loosening of strict Islamic regulations. By 2005, however, more conservative elements were back in control and a new crackdown on women’s clothing soon surfaced. A heavily disputed election in 2009 revealed substantial opposition to the country’s rigid Islamic regime, and a more moderate leadership returned to power in 2013. Iran’s ongoing Islamic revolution, however, did not mean the abandonment of economic modernity. The country’s oil revenues continued to fund its development, and by the early twenty-first century Iran was actively pursuing nuclear power and perhaps nuclear weapons, in defiance of Western opposition to these policies.