Reglobalization

These conditions provided the foundations for a dramatic quickening of global economic transactions after World War II, a “reglobalization” of the world economy following the contractions of the 1930s. This immensely significant process was expressed in the accelerating circulation of goods, capital, and people.

Connection

In what ways has economic globalization more closely linked the world’s peoples?

World trade, for example, skyrocketed from a value of some $57 billion in 1947 to about $18.3 trillion in 2012. Department stores and supermarkets around the world stocked their shelves with goods from every part of the globe. Twinings of London marketed its 120 blends of tea in more than 100 countries, and the Australian-

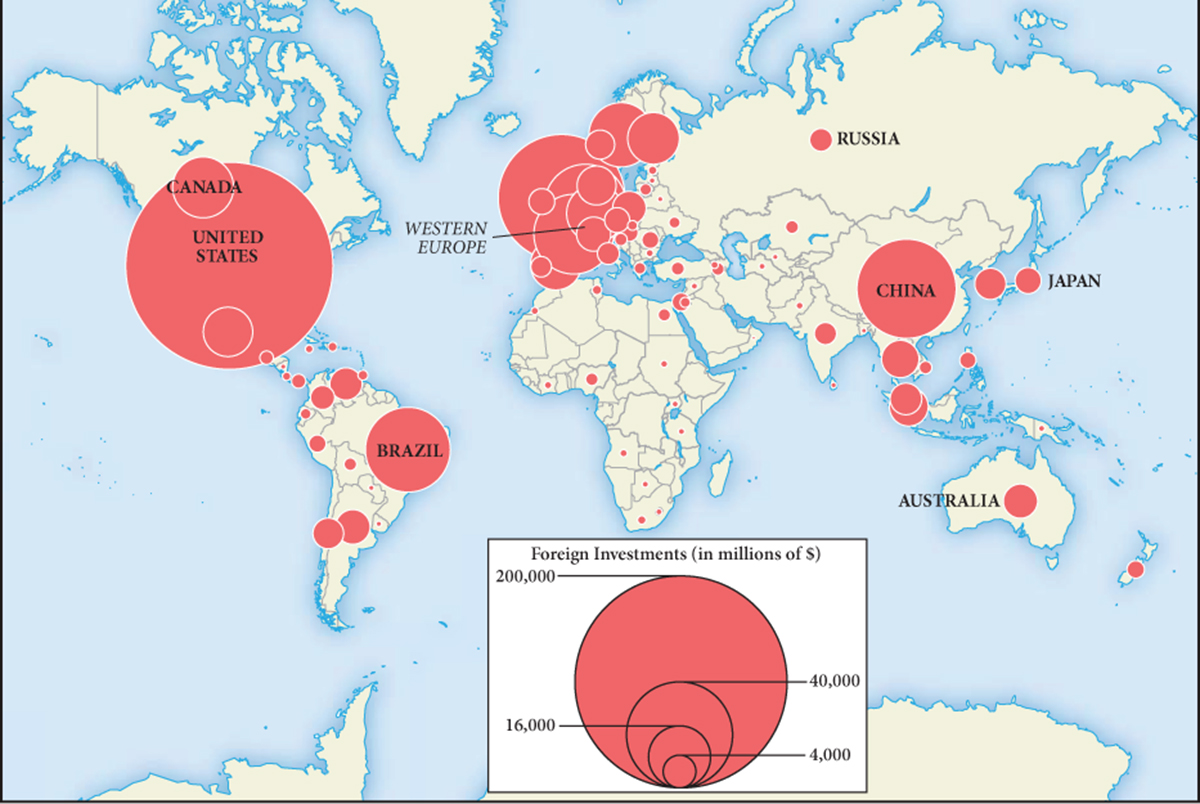

Money as well as goods achieved an amazing global mobility in three ways. The first was “foreign direct investment,” whereby a firm in, say, the United States opens a factory in China or Mexico (see Map 23.1). Such investment exploded after 1960 as companies in rich countries sought to take advantage of cheap labor, tax breaks, and looser environmental regulations in developing countries. A second form of money in motion has been the short-

Central to the acceleration of economic globalization have been huge global businesses known as transnational corporations (TNCs), which produce goods or deliver services simultaneously in many countries. For example, Mattel Corporation produced Barbie, that quintessentially American doll, in factories located in Indonesia, Malaysia, and China, using molds from the United States, plastic and hair from Taiwan and Japan, and cotton cloth from China. From distribution centers in Hong Kong, more than a billion Barbies were sold in 150 countries by 1999. Burgeoning in number since the 1960s, those TNCs, such as Royal Dutch Shell, Sony, and General Motors, often were of such an enormous size and had such economic clout that their assets and power dwarfed that of many countries. By 2000, 51 of the world’s 100 largest economic units were in fact TNCs, not countries. In the permissive economic climate of recent decades, such firms have been able to move their facilities quickly from place to place in search of the lowest labor costs or the least restrictive environmental regulations. During one five-

Accompanying the movement of goods and capital in the globalizing world of the twentieth century were new patterns of human migration, driven by war, revolution, poverty, and the end of empire. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire following World War I witnessed a large-

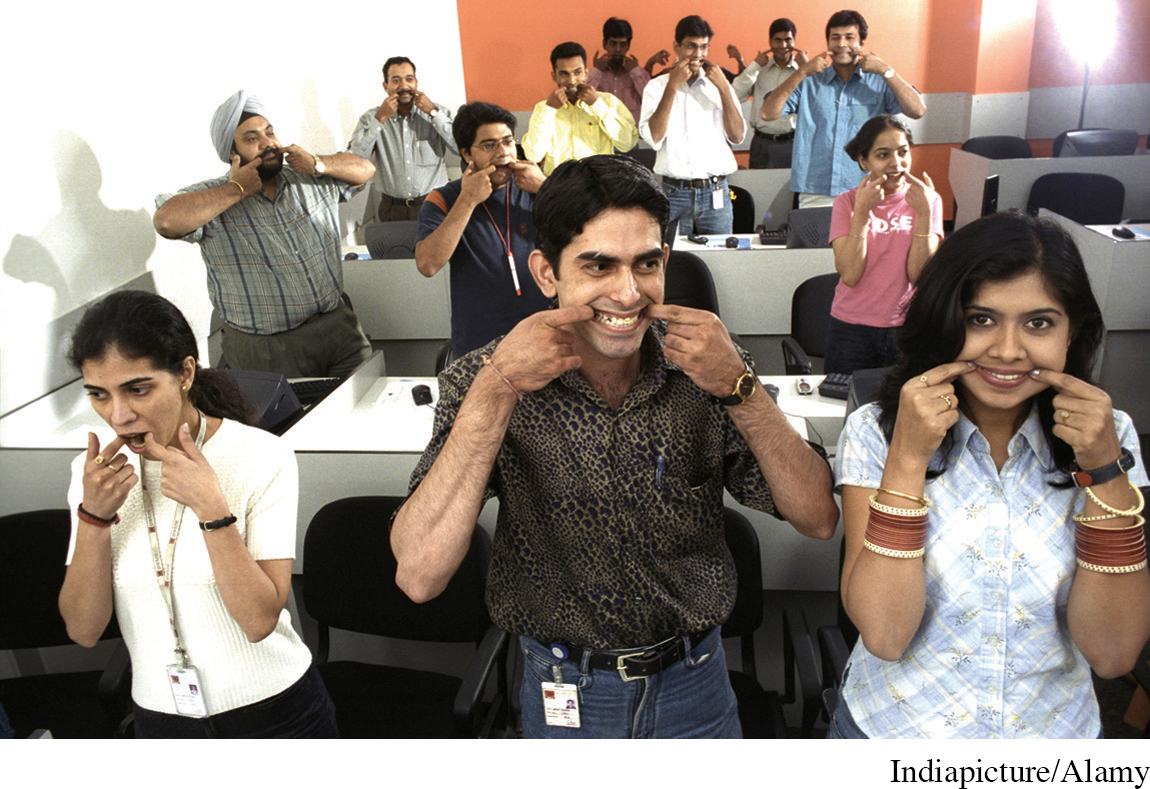

But perhaps the most significant pattern of global migration since the 1960s has featured a vast movement of people from the developing countries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America to the industrialized world of Europe and North America. Pakistanis, Indians, and West Indians moved to Great Britain; Algerians and West Africans to France; Turks and Kurds to Germany; Filipinos, Koreans, Cubans, Mexicans, and Haitians to the United States. A considerable majority of these people have been dubbed “labor migrants.” Most moved, often illegally and with few skills, to escape poverty in their own lands, drawn by an awareness of Western prosperity and a belief that a better future awaited them in the developed countries. By 2003, some 4 million Filipino domestic workers were employed in 130 countries. Young women by the hundreds of thousands from poor countries have been recruited as sex workers in wealthier nations, sometimes in conditions approaching slavery. Smaller numbers of highly skilled and university-

Many of those people in motion were headed for the United States, drawn by its reputation for wealth and opportunity. In the forty years between 1971 and 2010, almost 20 million immigrants arrived in the United States legally, and millions more entered illegally, the vast majority of both from the Latin American/Caribbean region and from Asia. Mexicans have been by far the largest group of immigrants to the United States, and many have arrived without legal documentation, an estimated 6.65 million during the first decade of the twenty-