Globalization and an American Empire

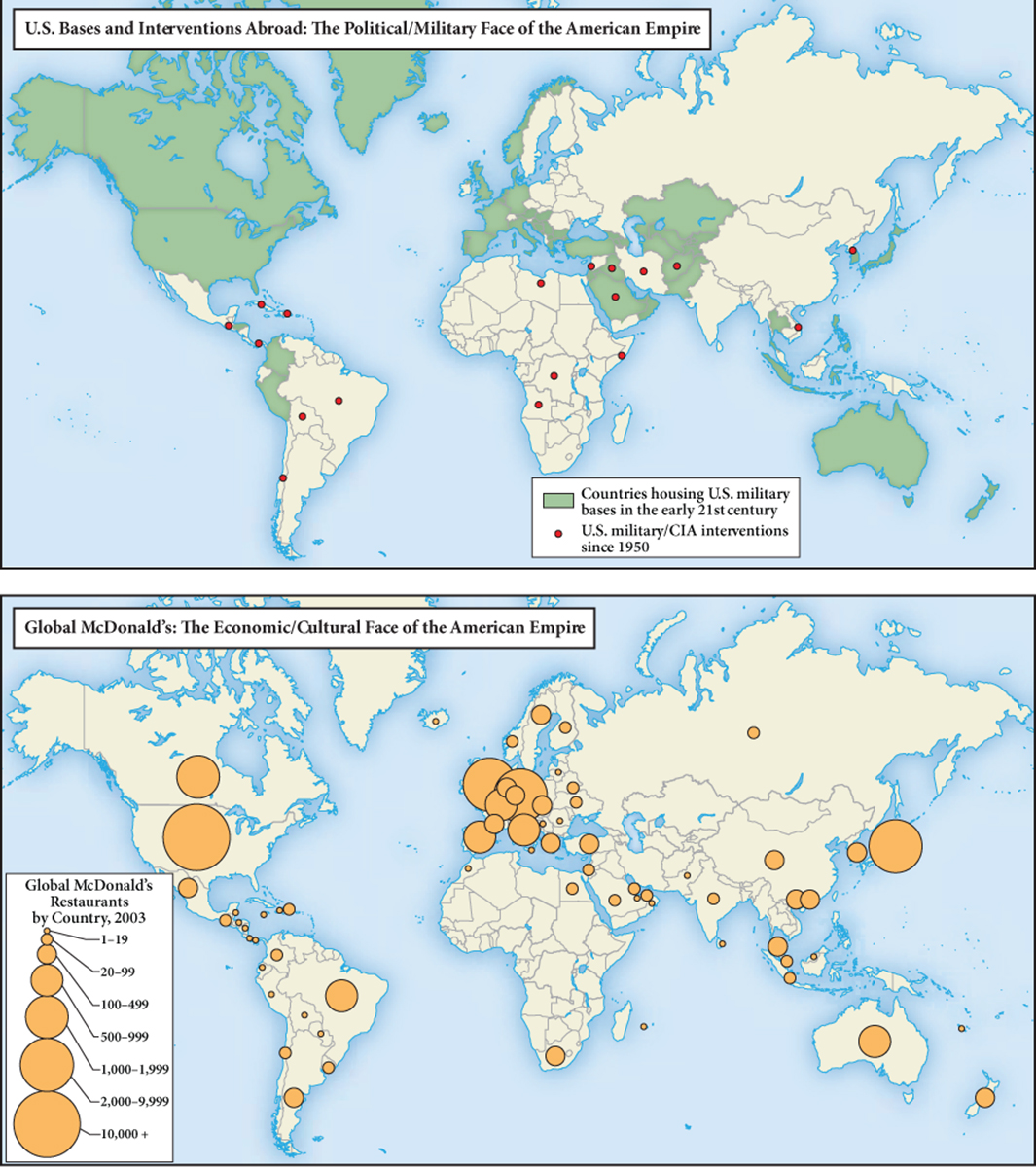

For many people, opposition to this kind of globalization also expressed resistance to mounting American power and influence in the world. An “American Empire,” some have argued, is the face of globalization (see Map 23.2), but scholars, commentators, and politicians have disagreed about how best to describe the United States’ role in the postwar world. Certainly it has not been a colonial territorial empire such as that of the British or the French in the nineteenth century. Seeking to distinguish themselves from Europeans, Americans generally have vigorously denied that they have an empire at all.

In some ways, the U.S. global presence might be seen as an “informal empire,” similar to the ones that Europeans exercised in China and the Middle East during the nineteenth century. In both cases, dominant powers sought to use economic penetration, political pressure, and periodic military action to create societies and governments compatible with their values and interests, but without directly governing large populations for long periods. In its economic dimension, American dominance has been termed an “empire of production,” which uses its immense wealth to entice or intimidate potential collaborators.10 Some scholars have emphasized the United States’ frequent use of force around the world, while others have focused attention on the “soft power” of its cultural attractiveness, its political and cultural freedoms, the economic benefits of cooperation, and the general willingness of many to follow the American lead voluntarily.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the cold war by the early 1990s, U.S. military dominance was unchecked by any equivalent power. When the United States was attacked by Islamic militants on September 11, 2001, that power was unleashed first against Afghanistan (2001), which had sheltered the al-

Since the 1980s, as its relative military strength has peaked, the United States has faced growing international economic competition. The recovery of Europe and Japan and the emergent industrialization of South Korea, Taiwan, China, and India substantially reduced the United States’ share of overall world production from about 50 percent in 1945 to 20 percent in the 1980s. By 2008 the United States accounted for just 8.1 percent of world merchandise exports. Accompanying this relative decline was a sharp reversal of the country’s trade balance as U.S. imports greatly exceeded its exports. In 2014 the World Bank reported that China had overtaken the United States as the world’s largest economy, even as it held much of the mounting American national debt.

However it might be defined, the exercise of American power, like that of many empires, was resisted abroad and contested at home. In Korea, Vietnam, Cuba, Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, armed struggle against U.S. intervention was both costly and painful. During the cold war, the governments of India, Egypt, and Ethiopia sought to diminish American influence in their affairs by turning to the Soviet Union or playing off the two superpowers against each other. Even France, resenting U.S. domination, withdrew from the military structure of NATO in 1967 and expelled all foreign-

Within the United States as well, the global exercise of American power generated controversy. The Vietnam War, for example, divided the United States more sharply than at any time since the Civil War. It split families and friendships, churches and political parties. The war provided a platform for a growing number of critics, both at home and abroad, who had come to resent American cultural and economic dominance in the post-