ZOOMING IN: Nalanda, India’s Buddhist University

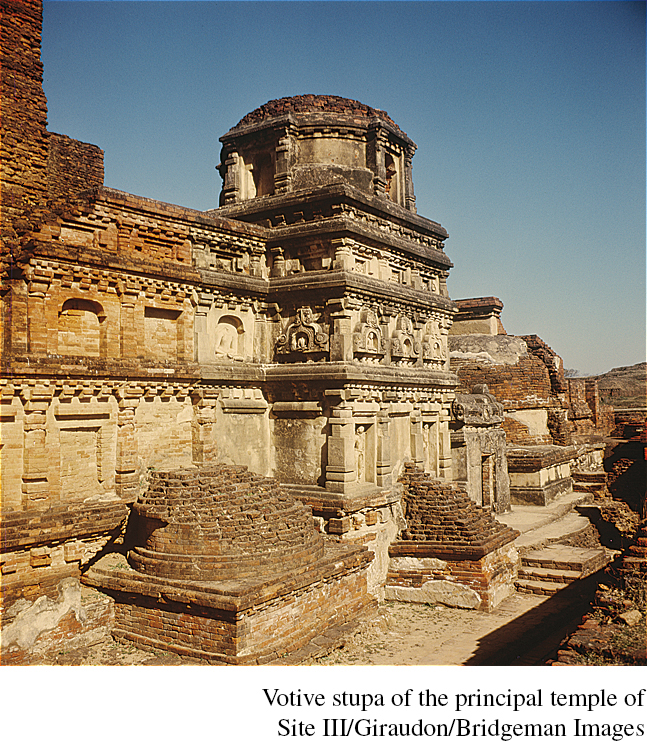

Nalanda, a village in the Bihar region of northeastern India, has a storied past in the world of Buddhism, for tradition has it that the Buddha himself visited on several occasions and the Mauryan dynasty emperor Ashoka built a temple there. But the village came to a wider prominence much later during the fifth century C.E. when a huge monastic complex, dedicated to Buddhist learning, began to take shape. Many have viewed it as the world’s first university. With eight separate compounds, ten temples, many meditation halls and classrooms, and numerous sculptures, Nalanda was a stunning architectural achievement.

Patronized by the emperors of India’s Gupta dynasty and later rulers, Nalanda was supported by the dedicated revenue from 100 or more villages in the region and operated under state supervision. Students, numbering in the many thousands, lived in dormitories and were taught by hundreds of instructors. Scholars and students alike came to Nalanda from all over the Buddhist world and beyond—

If the student body was international, the curriculum was likewise inclusive. While focused on distinctly Buddhist writings, students also studied Hindu sacred texts, Sanskrit grammar, logic, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy. Numerous Buddhist images were joined by those representing Hindu deities. Nalanda was a cosmopolitan place of lively discussion and controversy among rival schools of thought.

Visitors from the more remote regions of the Buddhist world were stunned at what they witnessed at Nalanda. In the seventh century C.E., the Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang recorded some of his impressions:

Ten thousand monks always lived there, both hosts and guests. They studied Mahayana [Buddhist] teachings and the doctrines of the eighteen schools, as well as worldly books such as the [Hindu] Vedas. They also learned about works on logic, grammar, medicine, and divination…. Lectures were given at more than a hundred places in the monastery every day, and the students studied diligently without wasting a single moment. As all the monks who lived there were men of virtue, the atmosphere in the monastery was naturally solemn and dignified. For more than seven hundred years since its establishment, none of the monks had committed any offence.12

Xuanzang’s comments about the “solemn and dignified” atmosphere of Nalanda may have been a little exaggerated, for reports of dice and board games, tumbling, shooting marbles, sword play, and even performances by dancing girls cast a somewhat different picture. Students apparently will be students.

Turkish Muslim invasions of India around 1200 badly damaged Nalanda; many monks were killed, others fled to Tibet or Nepal, and the library was burned. A Tibetan visitor in 1235 found a much-

The spectacular ruins of Nalanda began to be excavated in the nineteenth century when India was a British colony. And in 2014, a new, revived, and modern Nalanda University, now a secular institution, welcomed students for the first time, some 1,500 years after the opening of the original Nalanda complex.

Questions: What is most striking to you about Nalanda? How might the experiences of its students compare to your university experience? In what ways did Nalanda’s influence stretch beyond India’s borders and persist even after its collapse?