The Daoist Answer

No civilization has ever painted its cultural outlook in a single color. As Confucian thinking became generally known in China, a quite different school of thought also took shape. Known as Daoism, it was associated with the legendary figure Laozi, who, according to tradition, was a sixth-

Comparison

How did the Daoist outlook differ from that of Confucianism?

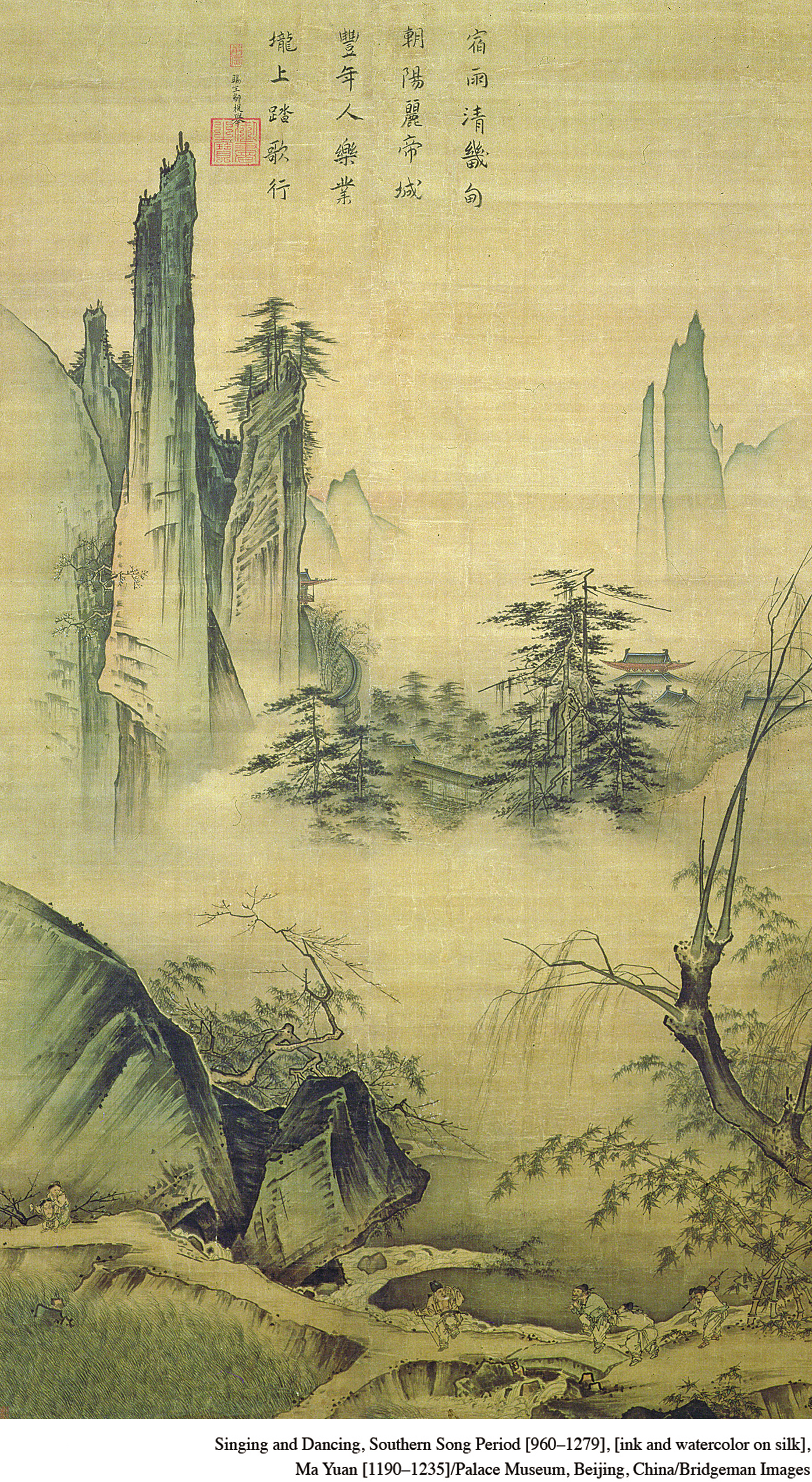

In many ways, Daoist thinking ran counter to that of Confucius, who had emphasized the importance of education and earnest striving for moral improvement and good government. The Daoists ridiculed such efforts as artificial and useless, claiming that they generally made things worse. In the face of China’s disorder and chaos, Daoists urged withdrawal into the world of nature and encouraged behavior that was spontaneous, individualistic, and natural. Whereas Confucius focused on the world of human relationships, the Daoists turned the spotlight on the immense realm of nature and its mysterious unfolding patterns. “Confucius roams within society,” the Chinese have often said. “Laozi wanders beyond.”

The central concept of Daoist thinking is dao, an elusive notion that refers to the way of nature, the underlying and unchanging principle that governs all natural phenomena. The dao “moves around and around, but does not on this account suffer,” wrote Laozi in the Daodejing. “All life comes from it. It wraps everything with its love as in a garment, and yet it claims no honor, for it does not demand to be lord. I do not know its name and so I call it the Dao, the Way, and I rejoice in its power.”6

Amid the world of civilization, so highly valued by Confucius, the Daoists yearned for an earlier time, “an age of perfect virtue” that had been disrupted by Confucian striving for something better. Then, according to one Daoist master, “there were no paths and ramps on the mountains and no boats upon the bridges…. There were vast numbers of animals and grasses, and trees reached their natural growth. Wild animals could be taken for walks on leashes, and one could climb up to the nests of magpies and other birds.” Such a vision of human harmony with nature contrasted sharply with the Confucian outlook, which urged “the development of a world of culture from a nature experienced as hostile.” To Confucians, humankind “disposes over the world of [wild] things, tames wild animals, and brings cowed vermin under his control.”7 Thus individual Daoists often fled to the mountains, where they might experience the dao in union with nature. Li Po, a much-

The birds have vanished into the sky,

And now the last cloud drains away.

We sit together, the mountain and me,

until only the mountain remains.8

Applied to human life, Daoism invited people to withdraw from the world of political and social activism, to disengage from the public life so important to Confucius, and to align themselves with the way of nature. It meant simplicity in living, small self-

Though there were individuals with the abilities of ten or a hundred men, there should be no employment of them …;

Though they had boats and carriages, they should have no occasion to ride in them; though they had buff coats and sharp weapons, they should have no occasion to use them.

I would make the people return to the use of knotted cords (instead of written characters).

They should think their (coarse) food sweet; their (plain) clothes beautiful; their (poor) dwellings places of rest; and their common (simple) ways sources of enjoyment.

There should be a neighbouring state within sight …,

but I would make the people … not have any intercourse with it.9

Like Confucianism, the Daoist perspective viewed family life as central to Chinese society, though the element of male/female hierarchy was downplayed in favor of complementarity and balance between the sexes.

Despite its various differences with the ideas of Confucianism, the Daoist perspective was widely regarded by elite Chinese as complementing rather than contradicting Confucian values (see the chapter-opening image). Such an outlook was facilitated by the ancient Chinese concept of yin and yang, which expressed a belief in the unity of opposites (see figure).

Thus a scholar-