ZOOMING IN: Ge Hong, a Chinese Scholar in Troubled Times

Had Ge Hong lived at a different time, he might have pursued the life of a Confucian scholar and civil servant, for he was born to a well-

Ge Hong’s family directly experienced the disorder when the family library was destroyed during the repeated wars of the time. Furthermore, the family patriarch, Ge Hong’s father, died when the young boy was only thirteen years old, an event that brought hardship and a degree of impoverishment to the family. Ge Hong reported later in his autobiography that he had to “walk long distances to borrow books” and that he cut and sold firewood to buy paper and brushes. Nonetheless, like other young men of his class, he received a solid education, reading the classic texts of Confucianism along with history and philosophy.

At about the age of fourteen or fifteen, Ge Hong began to study with the aged Daoist master Zheng Yin. He had to sweep the floor and perform other menial chores for the master while gaining access to rare and precious texts of the esoteric and alchemical arts aimed at creating the “gold elixir” that could promote longevity and transcendence. Withdrawal into an interior life, reflected in both Daoist and Buddhist thought, had a growing appeal to the elite classes of China in response to the political disturbances and disorder of public life. It was the beginning of a lifelong quest for Ge Hong.

And yet the Confucian emphasis on office holding, public service, and moral behavior in society persisted, sending Ge Hong into a series of military positions. Here too was a reflection of the disordered times of his life, for in more settled circumstances, young elite men would have disdained military service, favoring a career in the civil bureaucracy. Thus in 303, at the age of twenty, he organized and led a small group of soldiers to crush a local rebellion, later reporting that he alone among military leaders prevented his troops from looting the valuables of the enemy. For his service, he received the title of “wave conquering general” and 100 bolts of cloth. “I was the only one,” he wrote, “to distribute it among my officers, soldiers, and needy friends.” At several other points in his life as well, Ge Hong accepted official appointments, some of them honorary and others more substantive.

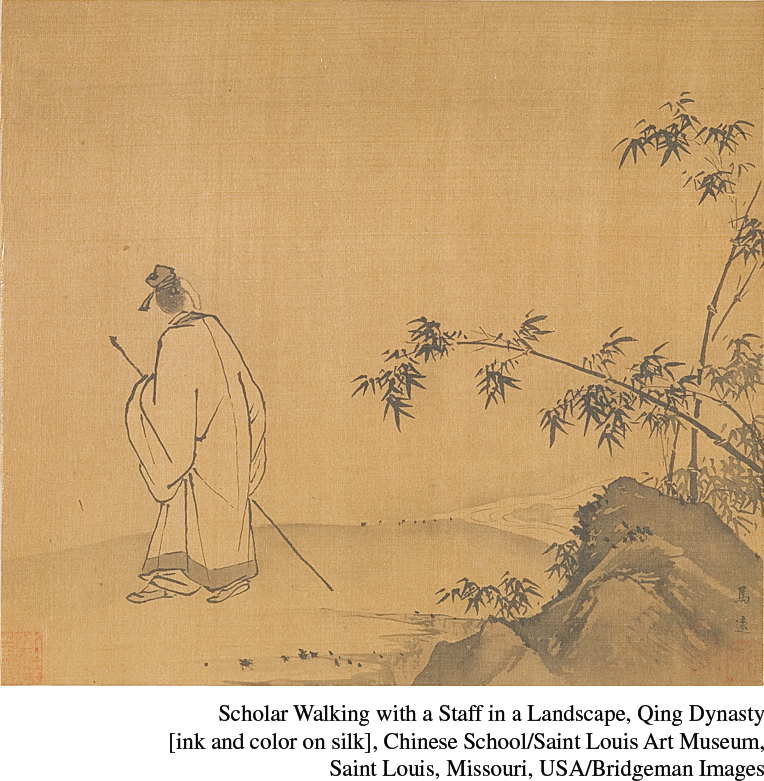

But his heart lay elsewhere, as he yearned for a more solitary and interior life. “Honor, high posts, power, and profit are like sojourning guests,” he wrote in his memoir. “They are not worth all the regret and blame, worry and anxiety they cause.” Thus he spent long periods of his life in relative seclusion, refusing a variety of official positions. “Unless I abandon worldly affairs,” he asked, “how can I practice the tranquil Way?” To Ge Hong, withdrawal was primarily for the purpose of seeking immortality, “to live as long as heaven and earth,” a quest given added urgency no doubt by the chaotic world of his own time. In his writings, he explored various techniques for enhancing qi, the vital energy that sustains all life, including breathing exercises, calisthenics, sexual practices, diet, and herbs. But it was the search for alchemically generated elixirs, especially those containing liquid gold and cinnabar (derived from mercury), that proved most compelling to Ge Hong. Much to his regret, he lacked the resources to obtain and process these rare ingredients.

However, Ge Hong did not totally abandon the Confucian tradition and its search for social order, for he argued in his writings that the moral virtues advocated by China’s ancient sage were a necessary prerequisite for attaining immortality. And he found a place in his philosophy also for the rewards and punishments of Legalist thinking. Thus he sought to reconcile the three major strands of Chinese thought—

Ge Hong spent the last years of his life on the sacred mountain of Luofu in the far south of China, continuing his immortality research until he died in 343 at the age of sixty. When his body was lifted into its coffin, contemporaries reported that it was “exceedingly light as if one were lifting empty clothing.”5 They concluded from this that Ge Hong had in fact achieved transcendence, joining the immortals in everlasting life, as he had so fervently hoped.

Question: In what ways did the larger conditions of China shape the life of Ge Hong?