ZOOMING IN: The Arabian Camel

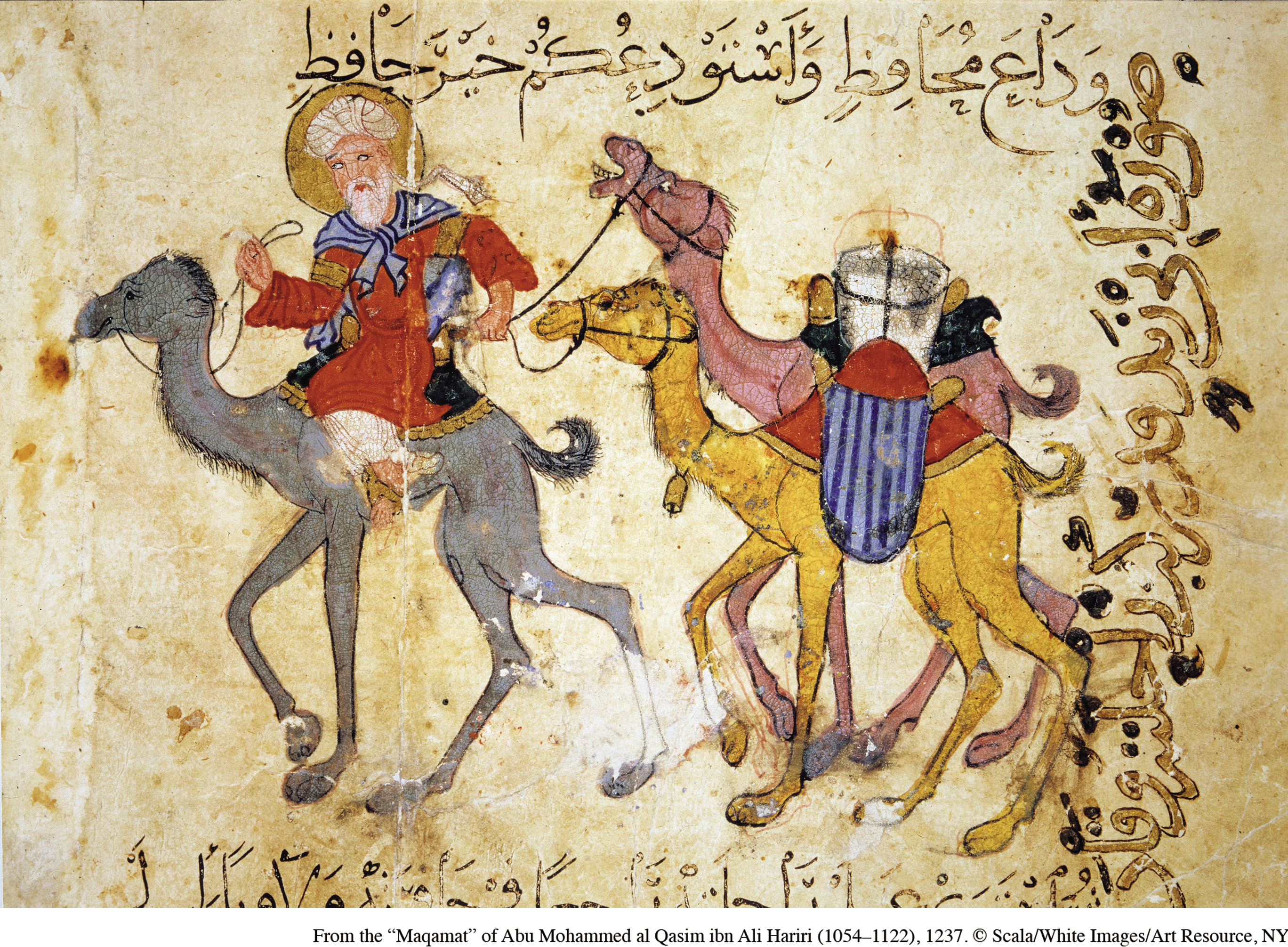

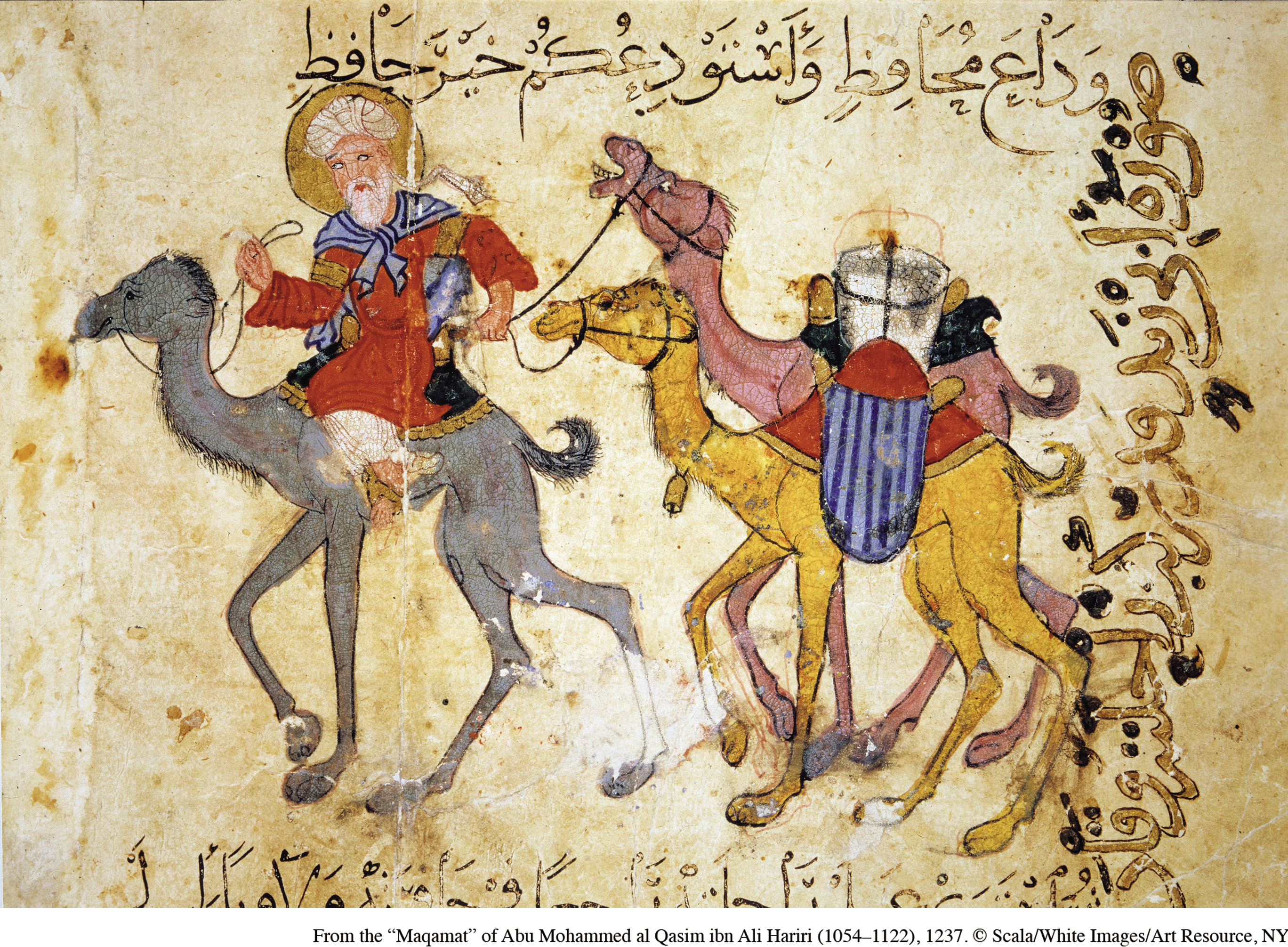

Part of a camel caravan. photo: From the “Maqamat” of Abu Mohammed al Qasim ibn Ali Hariri (1054–1122), 1237. © Scala/White Images/Art Resource, NY

Animals have their own histories, and they have long played a large role in human history as well. Consider the single-humped Arabian camel, for thousands of years an important means of transport and a beast of burden on the Silk and Sand Roads. Even today, the Arabian camel is a common sight across northern Africa and the Middle East. But it took millennia for this breed of camel to spread beyond its native Arabian Peninsula, where it had been domesticated by 3000 B.C.E. Camels were initially valued by Arab tribesmen for their milk; however, over time their endurance and ability to carry heavy loads resulted in their adoption as pack animals along the caravan routes between the frankincense- and myrrh-producing regions of southern Arabia and cities on the northern edges of the peninsula.

This trade slowly introduced Arabian camels to the rest of the Middle East, where they were well established by 500 B.C.E. But it was the invention of a new saddle, which allowed each animal to carry a heavier load, that transformed the camel into the most versatile and efficient form of transport in the region by 100 B.C.E. Ultimately the camel displaced the ox and cart, which for millennia had been a mainstay for moving goods. The advantages of the camel were significant. Camels ate desert plants that thrived on lands unsuitable to agriculture, while oxen required fodder grown on arable land. Moreover, camels carried loads on their backs rather than pulling carts made of wood, a scarce resource in the Middle East. In many parts of the region, the camel’s triumph was complete. By 500 C.E., wheeled vehicles had disappeared entirely from most of the Middle East, and the camel maintained its dominance for fifteen hundred years. In the 1780s, a French traveler in Syria commented, “It is noteworthy that in all of Syria no wagon or cart is seen.”16 Only with the emergence of the automobile in the twentieth century did the camel decisively lose its advantage over wheeled vehicles. From the Middle East, Arabian camels and related hybrid species moved along the Silk Roads, becoming a major means of transport as far away as modern Afghanistan. Only the cold climatic conditions of Central Asia halted their spread. In the frigid Gobi Desert, it was the Arabian camel’s cousin—the two-humped Bactrian camel—that traders relied upon to carry their loads.

The Arabian camel had perhaps an even more profound impact on long-distance trade across the Sahara. Before the arrival of the camel, the western Sahara proved an imposing barrier to trade. Just a trickle of goods flowed across the vast arid region, often through indirect exchange. The first camels most likely filtered into western Africa from the Middle East along the southern borders of the Sahara around 200 B.C.E., and they probably arrived after 100 C.E. in Roman North Africa, where they were used for a variety of purposes, including the plowing of fields. From the time of their arrival, camels stimulated trade and contact across the Sahara, but these exchanges really took off when the Arab conquerors of North Africa brought their expertise in camel caravan trading to the region in the sixth century C.E. At their height, caravans of up to 5,000 camels regularly crossed the Sahara on several established routes. It could take seventy days to traverse the desert, but profits from trade in gold, ivory, salt, and slaves made the journey worthwhile. These trade routes facilitated the emergence of empires in West Africa and the spread of Islam into the region. The Arabian camel remained the chief source of transport between sub-Saharan West Africa and the Mediterranean for over a thousand years, until European ships sailing along the Atlantic coast challenged their dominance in the fifteenth century.

Questions: Was the disappearance of the wheel an advance in terms of transport in the Middle East? What impact did the Arabian camel have on long-distance trade in Eurasia and Africa? How might reliance on the camel rather than the wheel affect human settlements?