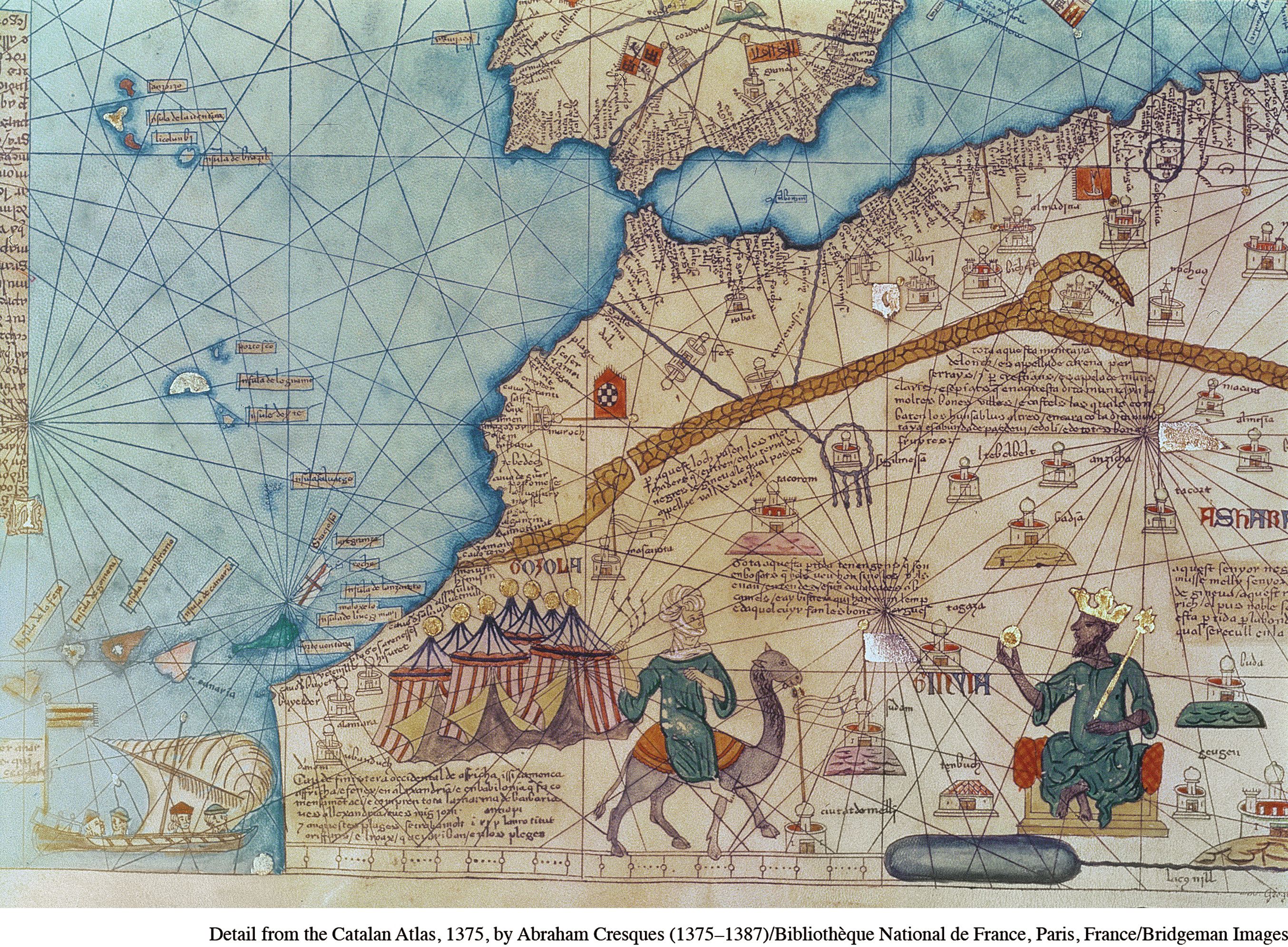

ZOOMING IN: Mansa Musa, West African Monarch and Muslim Pilgrim

In 1324, Mansa Musa, the ruler, or mansa, of the Kingdom of Mali, set out on an arduous journey from his West African homeland to the holy city of Mecca. His kingdom stretched from the Atlantic coast a thousand miles or more to the fabled inland city of Timbuktu and beyond, even as his pilgrimage to Mecca reflected the growing penetration of Islam in this emerging West African civilization. A pious Muslim, Mansa Musa was fluent in Arabic, was an avid builder of mosques, and was inclined on occasion to free a few slaves.

In the fourteenth century, Mali was an expanding empire. According to Musa, one of his immediate predecessors had launched a substantial maritime expedition “to discover the furthest limits of the Atlantic Ocean.”24 The voyagers never returned, and no other record of this trip exists, but it is intriguing to consider that Africans and Europeans alike may have been exploring the Atlantic at roughly the same time. Mansa Musa, however, was more inclined to expand on land as he sought access to the goldfields to the south and the trans-

Mansa Musa’s journey to Mecca fascinated observers at the time and continues to intrigue historians today. Such a pilgrimage has long been one of the duties—

When Mansa Musa began his journey in 1324, he was accompanied by an enormous entourage, with thousands of fellow pilgrims, some 500 slaves, his wife and other women, hundreds of camels, and a huge quantity of gold. It was the gold that attracted the most attention, as he distributed it lavishly along his journey. Egyptian sources reported that the value of gold in their country was depressed for years after his visit. On his return trip, Mansa Musa apparently had exhausted his supply and had to borrow money from Egyptian merchants at high interest rates. Those merchants also made a killing on Musa’s pilgrims, who, unsophisticated in big-

In Cairo, Mansa Musa displayed both his pride and his ignorance of Islamic law. Invited to see the sultan of Egypt, he was initially reluctant because of a protocol requirement to kiss the ground and the sultan’s hand. He consented only when he was persuaded that he was really prostrating before God, not the sultan. And in conversation with learned clerics, Mansa Musa was surprised to learn that Muslim rulers were not allowed to take the beautiful unmarried women of their realm as concubines. “By God, I did not know that,” he replied. “I hereby leave it and abandon it utterly.”26

In Mecca, Mansa Musa completed the requirements of the hajj, dressing in the common garb of all pilgrims, repeatedly circling the Kaaba, performing ritual prayers, and visiting various sites associated with Muhammad’s life, including a side trip to the Prophet’s tomb in Medina. He also sought to recruit a number of sharifs, prestigious descendants of Muhammad’s family, to add Islamic luster to his kingdom. After considerable difficulty and expense, he found four men who were willing to return with him to what Arabs understood to be the remote frontier of the Islamic world. Some reports suggested that they were simply freed slaves, hoping for better lives.

In the end, perhaps Mansa Musa’s goals for the pilgrimage were achieved. On a personal level, one source reported that he was so moved by the pilgrimage that he actually considered abandoning his throne altogether and returning to Mecca, where he might live as “a dweller near the sanctuary [the Kaaba].”27 His visit certainly elevated Mali’s status in the Islamic world. Some 200 years after that visit, one account of his pilgrimage placed the sultan of Mali as one of four major rulers in the Islamic world, equal to those of Baghdad and Egypt. Mansa Musa would have been pleased.

Question: What significance did Mansa Musa likely attach to his pilgrimage? How might Egyptians, Arabians, and Europeans have viewed it?