A Mongol Failure: The Invasion of Japan

T he Mongols are best known for their remarkable military victories, which gave them one of the largest empires in history, but they experienced stunning defeats as well.14 None was more dramatic than the failed invasion of Japan in 1281. The armada assembled by the Mongols for this campaign was one of the largest in history, comprising thousands of ships and as many as 140,000 sailors and soldiers. With little experience in naval warfare, the Mongols built their armada by drawing on the resources of their vassal state in Korea and their recently conquered subjects in China. But even with the aid of these seafaring peoples, this huge invasion fleet stretched the resources of the Mongols, who resorted to commuting the death sentences of criminals willing to serve in the fleet.

The invasion was the culmination of a deteriorating relationship between Japanese authorities and the Mongol ruler Khubilai Khan, grandson of Chinggis Khan and founder of the Chinese Yuan dynasty. In the 1260s, Japan’s government ignored the khan’s demands that it become a vassal state of the Mongol Empire. In 1274, the khan dispatched a raiding force against Japan that briefly landed on the main Japanese island of Kyushu. This force both scouted a suitable invasion route and put pressure on the Japanese to accept Mongol demands. In the years that followed, tensions increased, especially when the Japanese summarily beheaded Mongol envoys sent to demand their submission.

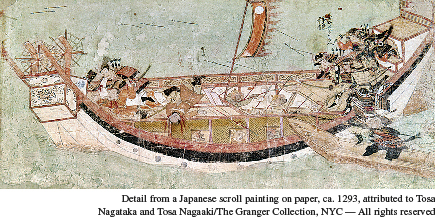

Following the final conquest of China in 1279, the khan shifted his attention to subjugating Japan. The massive invasion fleet sailed from ports in Korea and southern China with plans to combine off the shores of Japan. The fleet from Korea arrived first and attacked the mainland without waiting for the Chinese fleet. The Mongols sought to establish a beachhead at the site where Mongol forces had briefly come ashore in 1274, but the heavily outnumbered Japanese forces were waiting for them behind recently constructed defensive walls. Unable to establish a beachhead, the Mongol fleet anchored in the harbor, where it was attacked by groups of Japanese warriors, known as samurai, in small open boats, like the one depicted in a contemporary scroll recounting the battle (see photo above). In daring raids, often at night, the samurai boarded the much larger Mongol ships and engaged their crews in deadly close-

Under pressure, the Korean fleet withdrew and made its rendezvous with the Chinese fleet that had arrived in the waters off Japan. The combined forces then moved against another Japanese island, where they engaged in a fierce all-

The defeat had little impact on Khubilai Khan, whose empire recovered quickly from the setback. But the khan never again turned his attentions to Japan, instead seeking to expand his empire elsewhere, including the islands of Southeast Asia, the target of another ambitious but unsuccessful naval expedition in the 1290s. In Japan, the Mongol invasion had a much greater long-

Question: How does the Mongols’ military defeat at the hands of the Japanese shape your understanding of the Mongols and their empire?