European Comparisons: State Building and Cultural Renewal

At the other end of the Eurasian continent, similar processes of demographic recovery, political consolidation, cultural flowering, and overseas expansion were under way. Western Europe, having escaped Mongol conquest but devastated by the plague, began to regrow its population during the second half of the fifteenth century. As in China, the infrastructure of civilization proved a durable foundation for demographic and economic revival.

Guided Reading Question

▪COMPARISON

What political and cultural differences stand out in the histories of fifteenth-

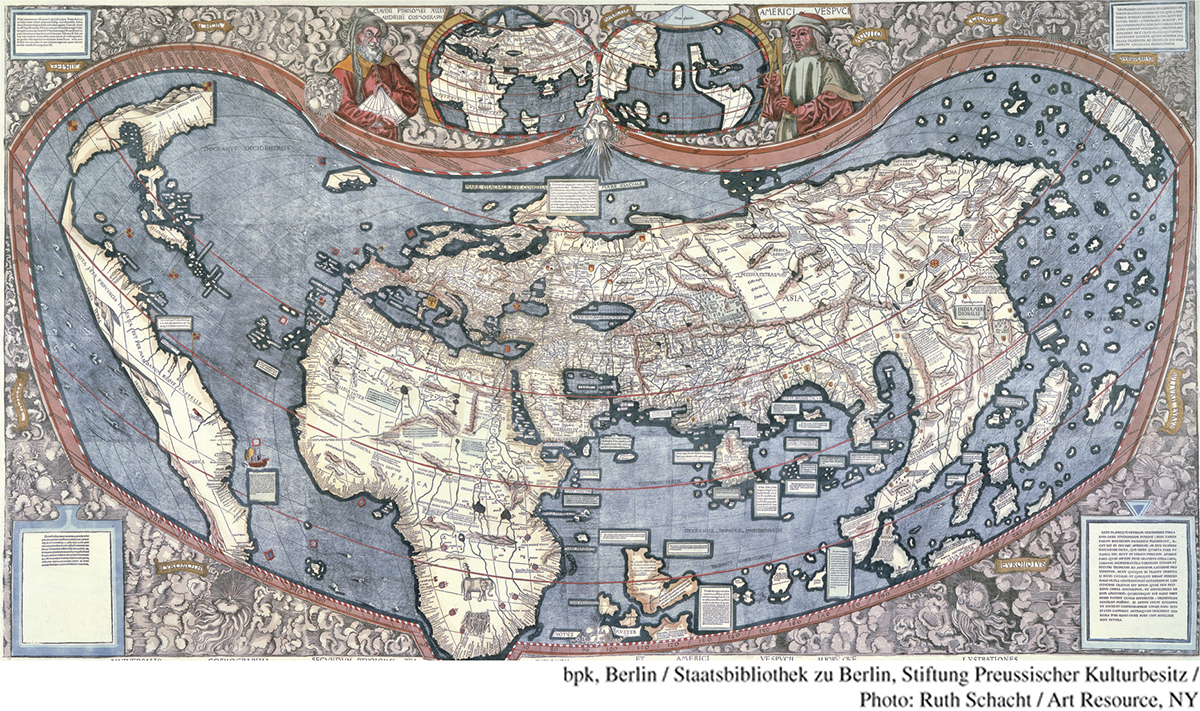

Politically too Europe joined China in continuing earlier patterns of state building. In China, however, this meant a unitary and centralized government that encompassed almost the whole of its civilization, while in Europe a decidedly fragmented system of many separate, independent, and highly competitive states made for a sharply divided Western civilization (see Map 12.2). Many of these states — Spain, Portugal, France, England, the city-

AP® EXAM TIP

One important feature of the Renaissance was that artists were funded by wealthy elites — part of a pattern since the beginning of civilizations.

A renewed cultural blossoming, known in European history as the Renaissance, likewise paralleled the revival of all things Confucian in Ming dynasty China. In Europe, however, that blossoming celebrated and reclaimed a classical Greco-

AP® EXAM TIP

Machiavelli’s political theories influenced totalitarian leaders of the early twentieth century (see Chapter 21.)

Although religious themes remained prominent, Renaissance artists now included portraits and busts of well-

One ought to be both feared and loved, but as it is difficult for the two to go together, it is much safer to be feared than loved…. For it may be said of men in general that they are ungrateful, voluble, dissemblers, anxious to avoid danger, and covetous of gain…. Fear is maintained by dread of punishment which never fails…. In the actions of men, and especially of princes, from which there is no appeal, the end justifies the means.6

While the great majority of Renaissance writers and artists were men, among the remarkable exceptions to that rule was Christine de Pizan (1363–1430), the daughter of a Venetian official, who lived mostly in Paris. Her writings pushed against the misogyny of so many European thinkers of the time. In her City of Ladies, she mobilized numerous women from history, Christian and pagan alike, to demonstrate that women too could be active members of society and deserved an education equal to that of men. Aiding in the construction of this allegorical city is Lady Reason, who offers to assist Christine in dispelling her poor opinion of her own sex. “No matter which way I looked at it,” she wrote, “I could find no evidence from my own experience to bear out such a negative view of female nature and habits. Even so … I could scarcely find a moral work by any author which didn’t devote some chapter or paragraph to attacking the female sex.”7

Heavily influenced by classical models, Renaissance figures were more interested in capturing the unique qualities of particular individuals and in describing the world as it was than in portraying or exploring eternal religious truths. In its focus on the affairs of this world, Renaissance culture reflected the urban bustle and commercial preoccupations of Italian cities. Its secular elements challenged the otherworldliness of Christian culture, and its individualism signaled the dawning of a more capitalist economy of private entrepreneurs. A new Europe was in the making, one more different from its own recent past than Ming dynasty China was from its pre-Mongol glory.