Western Christendom Fragmented: The Protestant Reformation

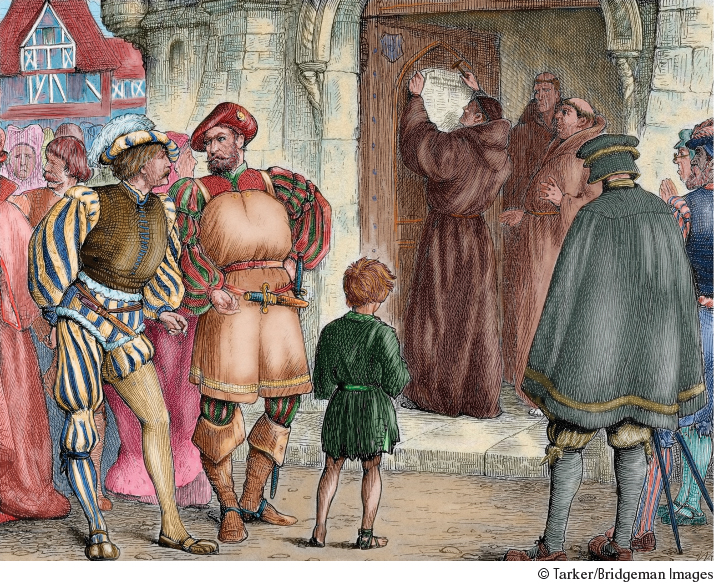

As if these were not troubles enough, in the early sixteenth century the Protestant Reformation shattered the unity of Roman Catholic Christianity, which for the previous 1,000 years had provided the cultural and organizational foundation of an emerging Western European civilization. The Reformation began in 1517 when a German priest, Martin Luther (1483–1546), publicly invited debate about various abuses within the Roman Catholic Church by issuing a document, known as the Ninety-

Guided Reading Question

▪CHANGE

In what ways did the Protestant Reformation transform European society, culture, and politics?

What made Luther’s protest potentially revolutionary, however, was its theological basis. A troubled and brooding man anxious about his relationship with God, Luther had recently come to a new understanding of salvation: he believed that it came through faith alone. Neither the good works of the sinner nor the sacraments of the Church had any bearing on the eternal destiny of the soul, for faith was a free gift of God, graciously granted to his needy and undeserving people. To Luther, the source of these beliefs, and of religious authority in general, was not the teaching of the Church, but the Bible alone, interpreted according to the individual’s conscience. All of this challenged the authority of the Church and called into question the special position of the clerical hierarchy and of the pope in particular. In sixteenth-century Europe, this was the stuff of revolution. (See the Snapshot, below, for a brief summary of Catholic and Protestant differences.)

AP® EXAM TIP

Take notes on the causes of the Protestant Reformation within Christianity.

Contrary to Luther’s original intentions, his ideas provoked a massive schism within the world of Catholic Christendom, for they came to express a variety of political, economic, and social tensions as well as religious differences. Some kings and princes, many of whom had long disputed the political authority of the pope, found in these ideas a justification for their own independence and an opportunity to gain the lands and taxes previously held by the Church. In the Protestant idea that all vocations were of equal merit, middle-

SNAPSHOTCatholic/Protestant Differences in the Sixteenth Century

| Catholic | Protestant | |

| Religious authority | Pope and church hierarchy | The Bible, as interpreted by individual Christians |

| Role of the pope | Ultimate authority in faith and doctrine | Authority of the pope denied |

| Ordination of clergy | Apostolic succession: direct line between original apostles and all subsequently ordained clergy | Apostolic succession denied; ordination by individual congregations or denominations |

| Salvation | Importance of church sacraments as channels of God’s grace | Importance of faith alone; God’s grace is freely and directly granted to believers |

| Status of Mary | Highly prominent, ranking just below Jesus; provides constant intercession for believers | Less prominent; Mary’s intercession on behalf of the faithful denied |

| Prayer | To God, but often through or with Mary and saints | To God alone; no role for Mary and saints |

| Holy Communion | Transubstantiation: bread and wine become the actual body and blood of Christ | Transubstantiation denied; bread and wine have a spiritual or symbolic significance |

| Role of clergy | Priests are generally celibate; sharp distinction between priests and laypeople; priests are mediators between God and humankind | Ministers may marry; priesthood of all believers; clergy have different functions (to preach, administer sacraments) but no distinct spiritual status |

| Role of saints | Prominent spiritual exemplars and intermediaries between God and humankind | Generally disdained as a source of idolatry; saints refer to all Christians |

Reformation thinking spread quickly both within and beyond Germany, thanks in large measure to the recent invention of the printing press. Luther’s many pamphlets and his translation of the New Testament into German were soon widely available. “God has appointed the [printing] Press to preach, whose voice the pope is never able to stop,” declared one Reformation leader.2 As the movement spread to France, Switzerland, England, and elsewhere, it also splintered, amoeba-like, into a variety of competing Protestant churches — Lutheran, Calvinist, Anglican, Quaker, Anabaptist — many of which subsequently subdivided, producing a bewildering array of Protestant denominations. Each was distinctive, but none gave allegiance to Rome or the pope.

AP® EXAM TIP

Pay attention to these political and social factors that divided Europe for centuries.

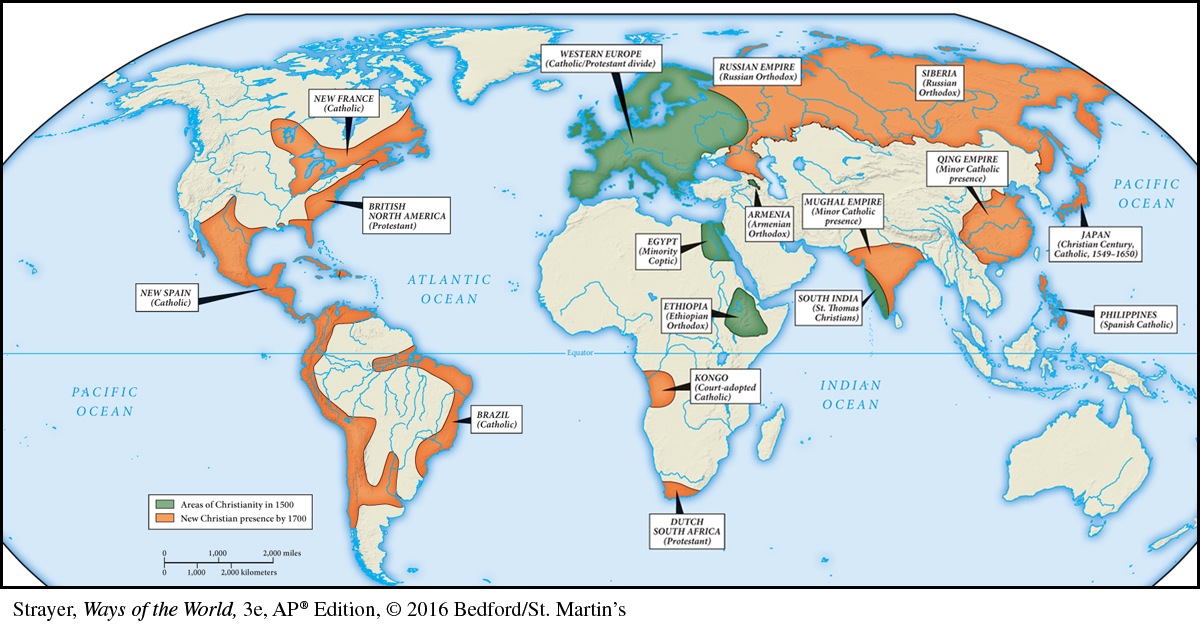

Thus to the sharp class divisions and the fractured political system of Europe was now added the potent brew of religious difference, operating both within and between states (see Map 15.1). For more than thirty years (1562–1598), French society was torn by violence between Catholics and the Protestant minority known as Huguenots (HYOO-

The Protestant breakaway, combined with reformist tendencies within the Catholic Church itself, provoked a Catholic Reformation, or Counter-

Although the Reformation was profoundly religious, it encouraged a skeptical attitude toward authority and tradition, for it had, after all, successfully challenged the immense prestige and power of the pope and the established Church. Protestant reformers fostered religious individualism, as people were now encouraged to read and interpret the scriptures for themselves and to seek salvation without the mediation of the Church. In the centuries that followed, some people turned that skepticism and the habit of thinking independently against all conventional religion. Thus the Protestant Reformation opened some space for new directions in European intellectual life.

In short, it was a more highly fragmented but also a renewed and revitalized Christianity that established itself around the world in the several centuries after 1500 (see Map 15.2).