Why Europe?

The Industrial Revolution has long been a source of great controversy among scholars. Why did it occur first in Europe? Within Europe, why did it occur earliest in Great Britain? And why did it take place in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries? Some explanations have sought the answer in unique and deeply rooted features of European society, history, or culture. One recent account, for example, argued that Europeans have been distinguished for several thousand years by a restless, creative, and freedom-

741

Guided Reading Question

▪CHANGE

In what respects did the roots of the Industrial Revolution lie within Europe? In what ways did that transformation have global roots?

Historians now know that other areas of the world had experienced times of great technological and scientific flourishing. Between 750 and 1100 C.E., the Islamic world generated major advances in shipbuilding, the use of tides and falling water to generate power, papermaking, textile production, chemical technologies, water mills, clocks, and much more.5 India had long been the world center of cotton textile production, the first place to turn sugarcane juice into crystallized sugar, and the source of many agricultural innovations and mathematical inventions. To the Arabs of the ninth century C.E., India was a “place of marvels.”6 More than either of these, China was clearly the world leader in technological innovation between 700 and 1400 C.E., prompting various scholars to suggest that China was on the edge of an industrial revolution by 1200 or so. For reasons much debated among historians, all of these flowerings of technological creativity had slowed down considerably or stagnated by the early modern era, when the pace of technological change in Europe began to pick up. But these earlier achievements certainly suggest that Europe was not alone in its capacity for technological innovation.

Nor did Europe enjoy any overall economic advantage as late as 1750. Over the past several decades, historians have carefully examined the economic conditions of various Eurasian societies in the eighteenth century and found “a world of surprising resemblances.” Economic indicators such as life expectancies, patterns of consumption and nutrition, wage levels, general living standards, widespread free markets, and prosperous merchant communities suggest broadly similar conditions across the major civilizations of Europe and Asia.7 Thus Europe had no obvious economic lead, even on the eve of the Industrial Revolution. Rather, according to one leading scholar, “there existed something of a global economic parity between the most advanced regions in the world economy.”8

A final reason for doubting a unique European capacity for industrial development lies in the relatively rapid spread of industrial techniques to many parts of the world over the past 250 years, a fairly short time by world history standards. Although the process has been highly uneven, industrialization has taken root, to one degree or another, in Japan, China, India, Brazil, Mexico, Turkey, Indonesia, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, South Korea, and elsewhere. Such a pattern weakens any suggestion that European culture or society was exceptionally compatible with industrial development.

742

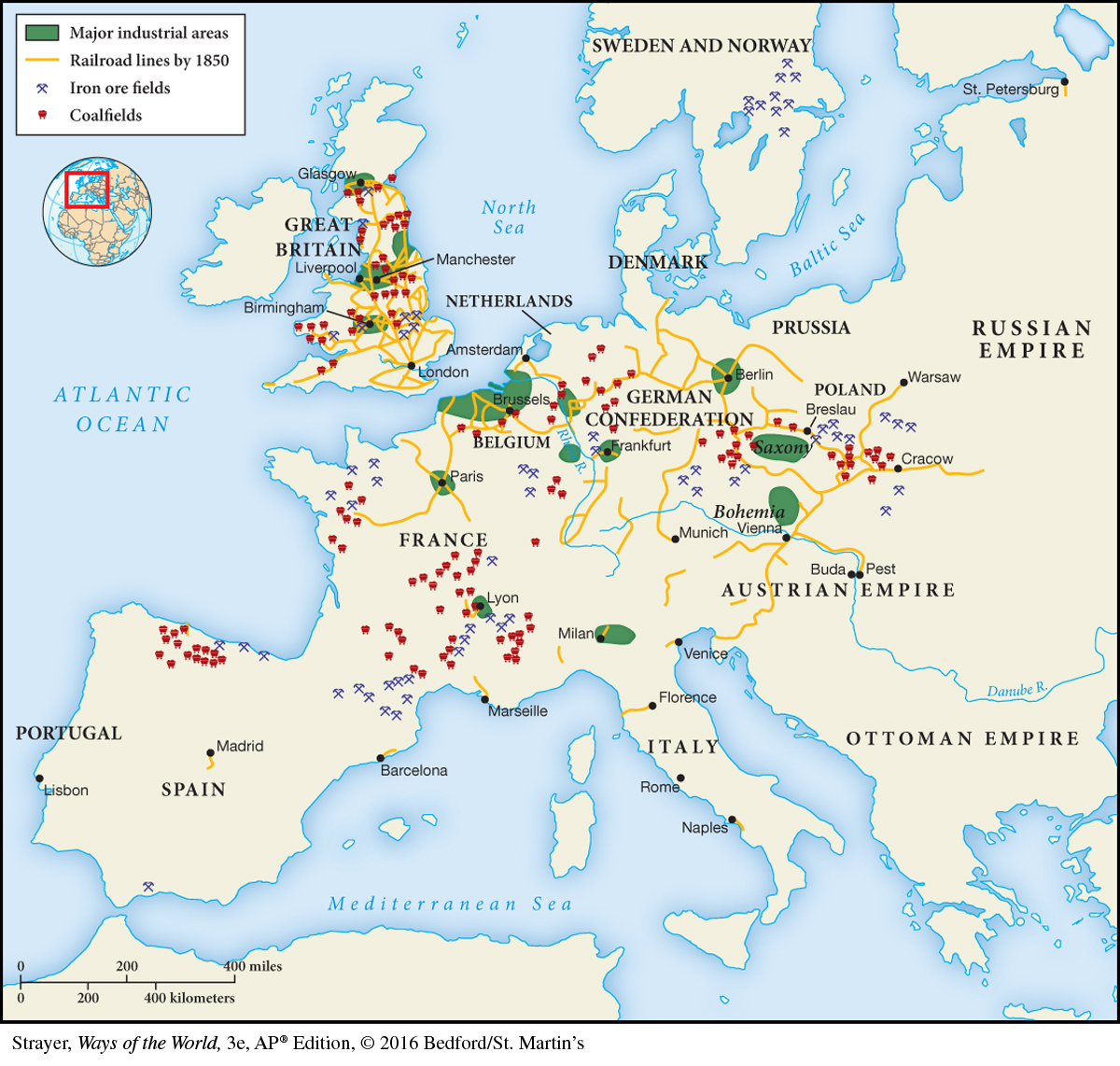

Thus, while sharp debate continues, many contemporary historians are inclined to see the Industrial Revolution erupting rather quickly and quite unexpectedly between 1750 and 1850 (see Map 17.1). Two intersecting factors help explain why this process occurred in Europe rather than elsewhere. One lies in certain patterns of Europe’s internal development that favored innovation. Its many small and highly competitive states, taking shape in the twelfth or thirteenth centuries, arguably provided an “insurance against economic and technological stagnation,” which the larger Chinese, Ottoman, or Mughal empires perhaps lacked.9 If so, then Western Europe’s failure to re-

AP® EXAM TIP

Notice that most industrial areas developed near sources of coal and iron.

AP® EXAM TIP

Government tax policies are an important continuity since the earliest days of civilization.

Furthermore, the relative newness of these European states and their monarchs’ desperate need for revenue in the absence of an effective tax-

Europe’s societies, of course, were not alone in developing market-

743

For example, Asia, home to the world’s richest and most sophisticated societies, was the initial destination of European voyages of exploration. The German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) encouraged Jesuit missionaries in China “not to worry so much about getting things European to the Chinese but rather about getting remarkable Chinese inventions to us.”11 Inexpensive and well-made Indian textiles began to flood into Europe, causing one English observer to note: “Almost everything that used to be made of wool or silk, relating either to dress of the women or the furniture of our houses, was supplied by the Indian trade.”12 The competitive stimulus of these Indian cotton textiles was certainly one factor driving innovation in the British textile industry. Likewise, the popularity of Chinese porcelain and Japanese lacquerware prompted imitation and innovation in England, France, and Holland.13 Thus competition from desirable, high-quality, and newly available Asian goods played a role in stimulating Europe’s Industrial Revolution.

744

In the Americas, Europeans found a windfall of silver that allowed them to operate in Asian markets. They also found timber, fish, maize, potatoes, and much else to sustain a growing population. Later, slave-produced cotton supplied an emerging textile industry with its key raw material at low prices, while sugar, similarly produced with slave labor, furnished cheap calories to European workers. “Europe’s Industrial Revolution,” concluded historian Peter Stearns, “stemmed in great part from Europe’s ability to draw disproportionately on world resources.”14 The new societies of the Americas further offered a growing market for European machine-produced goods and generated substantial profits for European merchants and entrepreneurs. None of the other empires of the early modern era enriched their imperial heartlands so greatly or provided such a spur to technological and economic growth.

Thus the intersection of new, highly commercialized, competitive European societies with the novel global network of their own making provides a context for understanding Europe’s Industrial Revolution. Commerce and cross-cultural exchange, acting in tandem, sustained the impressive technological changes of the first industrial societies.