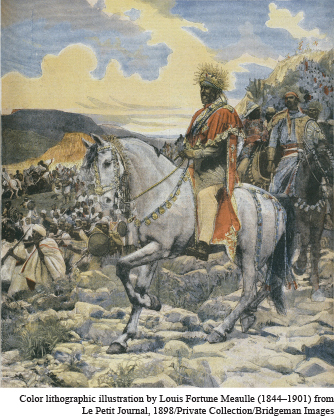

1896: The Battle of Adowa

O n March 1, 1896, two armies faced one another near the small town of Adowa in northern Ethiopia. On one side lay the Italian forces, who had intruded into Ethiopia from their adjacent colony of Eritrea, supplemented by a large number of African troops. On the other side stood the much larger Ethiopian army, personally led by Emperor Menelik II, accompanied by his forceful wife, Empress Taytu. The battle that followed proved a decisive victory for the Ethiopians and a rout for the Italians. That victory placed Ethiopia, like China, Persia, the Ottoman Empire, Japan, and Thailand, in the category of countries that retained their independence in an era of rampant European empire building. It was, in fact, the only part of Africa to enjoy that status. How had it happened?

One answer lies in circumstances. Ethiopia’s location in the mountainous highlands of eastern Africa made external invasion difficult. Its long tradition of independent statehood and a common Christian culture provided a strong sense of identity alongside the ethnic diversity of its population and the political rivalries of its governing elites. Ethiopia’s Italian adversary had become a unified country only in 1871 and possessed a less robust military than Britain, France, or Germany did. Nonetheless, as the scramble for Africa unfolded, the Italians had established colonial rule in both Somalia and Eritrea. Now they were seeking to enlarge their African holdings at the expense of Ethiopia.

Building on these circumstances, Menelik’s diplomacy and military strategy proved highly effective. After becoming emperor in 1889, Menelik actively took advantage of European rivalries for territory in northeastern Africa to pursue agreements with and to buy arms from Russia, France, Germany, Britain, and Italy. To obtain an agreement with Italy, he was willing to cede some territory in northern Ethiopia and to acknowledge Italian control of Eritrea in return for financial assistance and military supplies. But a dispute arose when the Italians interpreted the treaty as implying an Italian protectorate over Ethiopia. This, of course, Menelik decisively rejected. When Italian forces moved into Ethiopian territory in early 1895, he prepared for war.

Imposing a special tax to pay for more guns and ammunition, Menelik ordered the expulsion of all Italians from Ethiopia and called for national mobilization. Troops under the command of various regional rulers began to assemble, and in October 1895 a huge force began a five-

The echoes of Adowa resonated far and wide. For Italy, it was a national humiliation, “a shameful scar” according to a leading poet. That wound failed to heal and played a large role in motivating Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, a step on the road to World War II. As the avenger of Adowa, he had a large bust of himself placed on that battlefield.

For Ethiopia itself, Adowa had an immense significance that bears comparison with the experience of Japan. Like Japan, Ethiopia was a long-

But in another way, Ethiopian and Japanese history sharply diverged. Japan was able to join its political and military success with a thorough economic transformation of the country. Ethiopia was not able to do this and remains one of the least developed countries of the Global South. Menelik did initiate a number of modernizing projects — banks, railroads, schools, hospitals, and a few factories — but nothing approached the scale of Japan’s transformation. His success, in fact, strengthened the more conservative forces within Ethiopian society.

When I (Robert Strayer) taught high school history in Ethiopia in the mid-

Question: How might you describe the significance of the Battle of Adowa in Ethiopian, African, and world history?