Western Pressures

AP® EXAM TIP

You need to know that the Opium Wars were a major turning point in China’s decline in the nineteenth century.

Nowhere was the shifting balance of global power in the nineteenth century more evident than in China’s changing relationship with Europe, a transformation that registered most dramatically in the famous Opium Wars. Derived from Arab traders in the eighth century or earlier, opium had long been used on a small scale as a drinkable medicine; it was regarded as a magical cure for dysentery and described by one poet as “fit for Buddha.”5 It did not become a serious problem until the late eighteenth century, when the British began to use opium, grown and processed in India, to cover their persistent trade imbalance with China. By the 1830s, British, American, and other Western merchants had found an enormous, growing, and very profitable market for this highly addictive drug. From 1,000 chests (each weighing roughly 150 pounds) in 1773, China’s opium imports exploded to more than 23,000 chests in 1832. (See Snapshot.)

SNAPSHOTChinese/British Trade at Canton, 1835–1836

What do these figures suggest about the role of opium in British trade with China? Calculate opium exports as a percentage of British exports to China, Britain’s trade deficit without opium, and its trade surplus with opium. What did this pattern mean for China?6

| Item | Value (in Spanish dollars) | |

| British Exports to Canton | Opium | 17,904,248 |

| Cotton | 8,357,394 | |

| All other items (sandalwood, lead, iron, tin, cotton yarn and piece goods, tin plates, watches, clocks) | 6,164,981 | |

| Total | 32,426,623 | |

| British Imports from Canton | Tea (black and green) | 13,412,243 |

| Raw silk | 3,764,115 | |

| Vermilion | 705,000 | |

| All other goods (sugar products, camphor, silver, gold, copper, musk) | 5,971,541 | |

| Total | 23,852,899 |

Guided Reading Question

▪CONNECTION

How did Western pressures stimulate change in China during the nineteenth century?

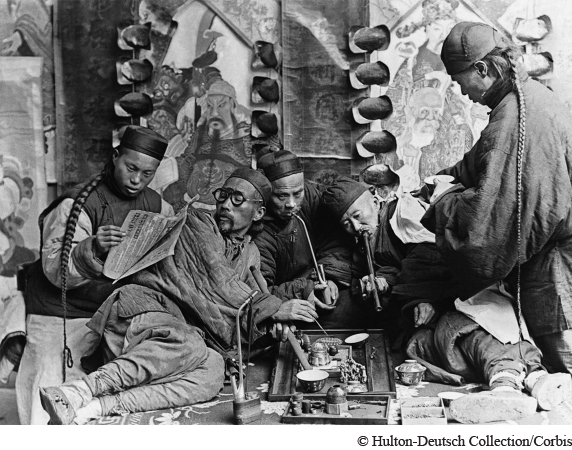

By then, Chinese authorities recognized a mounting problem on many levels. Because opium importation was illegal, it had to be smuggled into China, thus flouting Chinese law. Bribed to turn a blind eye to the illegal trade, many officials were corrupted. Furthermore, a massive outflow of silver to pay for the opium reversed China’s centuries-long ability to attract much of the world’s silver supply, and this imbalance caused serious economic problems. Finally, China found itself with many millions of addicts — men and women, court officials, students preparing for exams, soldiers going into combat, and common laborers seeking to overcome the pain and drudgery of their work. Following an extended debate at court in 1836 on whether to legalize the drug or crack down on its use, the emperor decided on suppression. An upright official, Commissioner Lin Zexu (lin zuh-SHOO), led the campaign against opium use as a kind of “drug czar.” (See Zooming In: Lin Zexu.) The British, offended by the seizure of their property in opium and emboldened by their new military power, sent a large naval expedition to China, determined to end the restrictive conditions under which they had long traded with that country. In the process, they would teach the Chinese a lesson about the virtues of free trade and the “proper” way to conduct relations among countries. Thus began the first Opium War, in which Britain’s industrialized military might proved decisive. The Treaty of Nanjing, which ended the war in 1842, largely on British terms, imposed numerous restrictions on Chinese sovereignty and opened five ports to European traders. Its provisions reflected the changed balance of global power that had emerged with Britain’s Industrial Revolution. To the Chinese, that agreement represented the first of the “unequal treaties” that seriously eroded China’s independence by the end of the century.

But it was not the last of those treaties. Britain’s victory in a second Opium War (1856–1858) was accompanied by the brutal vandalizing of the emperor’s exquisite Summer Palace outside Beijing and resulted in further humiliations. Still more ports were opened to foreign traders. Now those foreigners were allowed to travel freely and buy land in China, to preach Christianity under the protection of Chinese authorities, and to patrol some of China’s rivers. Furthermore, the Chinese were forbidden to use the character for “barbarians” to refer to the British in official documents. Following military defeats at the hands of the French (1885) and Japanese (1895), China lost control of Vietnam, Korea, and Taiwan. By the end of the century, the Western nations plus Japan and Russia had all carved out spheres of influence within China, granting themselves special privileges to establish military bases, extract raw materials, and build railroads. Many Chinese believed that their country was being “carved up like a melon” (see Map 19.1 and the chapter-opening photo).

AP® EXAM TIP

Make comparisons between this map showing a divided China and Map 13.3 showing a unified China.

Coupled with its internal crisis, China’s encounter with European imperialism had reduced the proud Middle Kingdom to dependency on the Western powers as it became part of a European-based “informal empire.” China was no longer the center of civilization to which barbarians paid homage and tribute, but just one weak and dependent nation among many others. The Qing dynasty remained in power, but in a weakened condition, which served European interests well and Chinese interests poorly. Restrictions imposed by the unequal treaties clearly inhibited China’s industrialization, as foreign goods and foreign investment flooded the country largely unrestricted. Chinese businessmen mostly served foreign firms, rather than developing as an independent capitalist class capable of leading China’s own Industrial Revolution.