Hiroshima

“I f the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky. That would be the splendor of the Mighty One.”13 This passage from the Bhagavad Gita, an ancient Hindu sacred text, occurred to J. Robert Oppenheimer, a leading scientist behind the American push to create a nuclear bomb, as he watched the first successful test of a nuclear weapon in the desert south of Santa Fe, New Mexico, on the evening of July 16, 1945. Years later, he recalled that another verse from the same sacred text had also entered his mind: “I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds.” And so the atomic age was born amid Oppenheimer’s thoughts of divine splendor and divine destruction.

Several weeks later, the whole world became aware of this new era when American forces destroyed the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with nuclear bombs. The U.S. government decided to use this powerful new weapon partially to hasten the end of World War II, but also to strengthen the United States’ position in relation to the Soviet Union in the postwar world. Whether the bomb was necessary to force Japan to surrender is a question of some historical debate. What is not in dispute was the horrific destruction and human suffering wrought by the two bombs. The centers of both cities were flattened, and as many as 80,000 inhabitants of Hiroshima and 40,000 of Nagasaki perished almost instantly from the force and intense heat of the explosions.

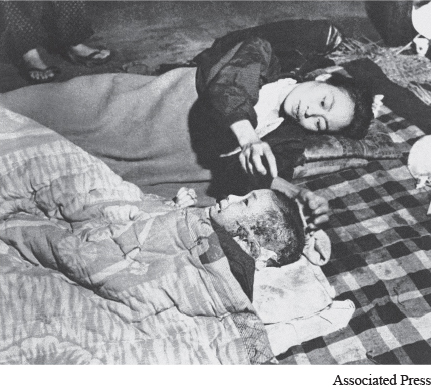

The harrowing accounts of survivors offer some sense of the suffering that followed. Iwao Nakamura, a schoolboy in Hiroshima who lived through the attack, recalled “old people pleading for water, tiny children seeking help, students unconsciously calling for their parents.” He remembered that “there was a mother prostrate on the ground, moaning with pain but with one arm still tightly embracing her dead baby.”15 But for many of these survivors, the suffering had only begun. It is estimated that by 1950 as many as 200,000 additional victims had succumbed to their injuries, especially burns and the terrible effects of radiation. Cancer and genetic deformations caused by exposure to radiation continue to affect survivors and their descendants today.

Human suffering on a massive scale was a defining feature of total war during the first half of the twentieth century. In this sense, the atomic bomb was just the latest development in an arms race that drew on advances in manufacturing, technology, and science to create ever more horrific weapons of mass destruction. But no other weapon from that period was as revolutionary as the atomic bomb, which made use of recent discoveries in theoretical physics to harness the fundamental forces of the universe for war. The subsequent development of those weapons has cast an enormous shadow on the world ever since.

That shadow lay in a capacity for destruction previously associated only with an apocalypse of divine origin. Now human beings have acquired that capacity. A single bomb in a single instant can obliterate any major city in the world, and the detonation of even a small fraction of the weapons in existence today would reduce much of the world to radioactive rubble and social chaos. The destructive power of nuclear weapons has led responsible scientists to contemplate the possible extinction of our species — by our own hands. It is hardly surprising that the ongoing threat of nuclear war has led many survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings to push for a world free of nuclear weapons by highlighting the human suffering that they cause. In a speech to a United Nations Special Session on Disarmament in 1982, Senji Yamaguchi, a survivor of the Nagasaki bombing, pleaded, “Please look closely at my [burnt] face and hands…. We, atomic bomb survivors, are calling out. I continue calling out as long as I am alive: no more Hiroshima, no more Nagasaki, no more war, no more [victims of nuclear attacks].”16

Question: How might you define both the short-