The Cuban Revolution

“Y ou Americans must realize what Cuba means to us old Bolsheviks,” declared a high-

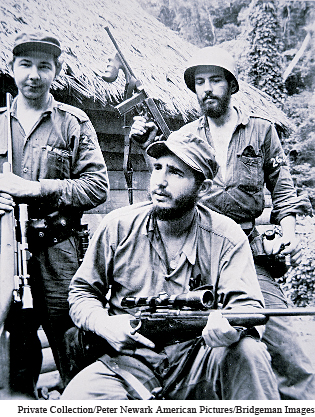

The armed revolt began disastrously. In 1953, the Cuban army defeated Castro and 123 of his supporters when they attacked two army barracks in what was their first major military operation. Castro himself was captured, sentenced to jail, and then released into exile. However, fortunes shifted in 1956, when Castro slipped back into Cuba and succeeded in bringing together many opponents of the current regime in an armed nationalist insurgency dedicated to radical economic and social reform. Upon seizing power in 1959, Castro and his government acted decisively to implement their revolutionary agenda. Within a year, they had effectively redistributed 15 percent of the nation’s wealth by granting land to the poor, increasing wages, and lowering rents. In the following year, the new government nationalized the property of both wealthy Cubans and U.S. corporations. Many Cubans, particularly among the elite, fled into exile. “The revolution,” declared Castro, “is the dictatorship of the exploited against the exploiters.”11

Economic and political pressure from the United States followed, culminating in the Bay of Pigs, a failed invasion of the island in 1961 by Cuban exiles with covert support from the U.S. government. American hostility pushed the revolutionary nationalist Castro closer to the Soviet Union, and gradually he began to think of himself and his revolution as Marxist. In response to Cuban pleas for support against American aggression, the Soviet premier Khrushchev deployed nuclear missiles on the island, sparking the Cuban missile crisis. While the compromise reached between the two superpowers resulted in the withdrawal of the missiles, it did include assurances from the United States that it would not attack Cuba.

In the decades that followed, Cuba sought to export its brand of revolution beyond its borders, especially in Latin America and Africa. Che Guevara, an Argentine who had fought in the Cuban Revolution, declared, “Our revolution is endangering all American possessions in Latin America. We are telling these countries to make their own revolution.”12 Cuba supported revolutionary movements in many regions; however, none succeeded in creating a lasting Cuban-

The legacy of the Cuban Revolution has been mixed. The new government devoted considerable resources to improving health and education on the island. By the mid-

However, earlier promises to establish a truly democratic system never materialized. Castro declared in 1959 that elections were unneeded because “this democracy … has found its expression, directly, in the intimate union and identification of the government with the people.”13 The state placed limits on free expression and arrested opponents or forced them into exile. Cuba has also failed to achieve the economic development originally envisioned at the time of the revolution. Sugar remains its chief export crop, and by the 1980s Cuba had become almost as economically dependent on the Soviet Union as it had been upon the United States. Desperate consequences followed when the Cuban economy shrank by a third following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Like communist experiments in the Soviet Union and China, Cuba experienced real improvements in living standards, especially for the poor, but these gains were accompanied by sharp restraints on personal freedoms and mixed results in the economy. Such have been the ambivalent outcomes of many revolutionary upheavals.

Question: Compare the Cuban Revolution to those in Russia and China. What are the similarities and differences?