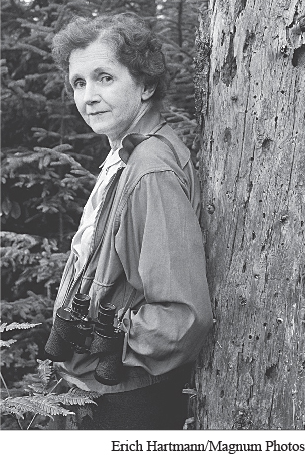

Rachel Carson, Pioneer of Environmentalism

“O ver increasingly large areas of the United States, spring now comes unheralded by the return of the birds, and the early mornings are strangely silent.”33 This was the appalling vision that inspired Silent Spring, a book that effectively launched the American environmental movement in 1962 with its devastating critique of unregulated pesticide use. Its author, Rachel Carson, was born in 1907 on a farm near Pittsburgh. Her childhood interest in nature led to college and graduate studies in biology and then a career as a marine biologist with the U.S. Department of Fisheries, where she was only the second woman hired for such a position. She was also finding her voice as a writer, penning three well-

Through this work, Carson gained an acute awareness of the intricate and interdependent web of life, but she assumed that “much of nature was forever beyond the tampering hand of man.” However, the advent of the atomic age, with the dramatic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, shook her confidence that nature was immune to human action, and she began to question the widely held assumption that science always held positive outcomes for human welfare. That skepticism gradually took shape around the issue of pesticides and other toxins deliberately introduced into the environment in the name of progress. In 1958, a letter from a friend describing the death of birds in her yard following aerial spraying for mosquito control prompted Carson to take on a project that became Silent Spring. Initially she called it “Man against the Earth.”

From government agencies, independent scientists, public health specialists, and her own network of contacts, Carson began to assemble data about the impact of pesticides on natural ecosystems and human health. While she never called for their complete elimination, she argued for much greater care and sensitivity to the environment in employing chemical pesticides. She further urged natural biotic agents as a preferable alternative for pest control. The book also criticized the government regulatory agencies for their negligent oversight and scientific specialists for their “fanatical zeal” to create “a chemically sterile insect-

When Silent Spring was finally published in 1962, the book provoked a firestorm of criticism. Velsicol, a major chemical company, threatened a lawsuit to prevent its publication. Critics declared that following her prescriptions would mean “the end of all human progress,” even a “return to the Dark Ages [when] insects and diseases and vermin would once again inherit the earth.” Some of the attacks were more personal. Rachel Carson had never married, and Ezra Taft Benson, a former secretary of agriculture, wondered “why a spinster with no children was so concerned about genetics,” while opining that she was “probably a communist.” It was the height of the cold war era, and challenges to government agencies and corporate capitalism were often deemed “un-American” and “sinister.”

Carson evoked such a backlash because she had called into question the whole idea of science as progress, so central to Western culture since the Enlightenment. Humankind had acquired the power to “alter the very nature of the [earth’s] life,” she declared. The book ended with a dire warning: “It is our alarming misfortune that so primitive a science has armed itself with the most modern and terrible weapons, and that in turning them against the insects, it has also turned them against the earth.”

But Carson also had a growing number of enthusiastic supporters. Before she died in 1964, she witnessed the vindication of much of her work. Honors and awards poured in; she more than held her own against her critics in a CBS News program devoted to her book; and a presidential Science Advisory Committee cited Carson’s work while recommending the “orderly reduction of persistent pesticides.” Following her death, a range of policy changes reflected her work, including the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 and the banning of the insecticide DDT in 1973. Silent Spring also motivated many to join the growing array of environmentalist groups.

Approaching her death, Carson applied her ecological understanding of the world to herself as well. In a letter to her best friend not long before she died, she recalled seeing some monarch butterflies leaving on a journey from which they would not return. And then she added: “When the intangible cycle has run its course, it is a natural and not unhappy thing that a life comes to an end.”

Question: In what larger contexts might we understand Rachel Carson and the book that gained her such attention?