The Spartacus Slave Revolt

D espite the prominence of slavery in ancient civilizations, large-scale slave revolts were rare. One of the most impressive began in the Roman Empire during the summer of 73 B.C.E. when around seventy slaves escaped from a gladiator school at Capua, about 125 miles south of Rome. Grabbing knives and skewers from the kitchen on their way out, this small band of men, who had been trained to fight to the death for the entertainment of spectators, established a stronghold on nearby Mount Vesuvius and chose as their leader Spartacus, described by the historian Sallust as “a man of immense bodily strength and spirit.”14 The defeat of Roman forces sent to seize them encouraged other slaves and some free men to join the rebellion. Their numbers eventually swelled to as many as 120,000 men, women, and children at the height of the uprising, reflecting the large number of slaves employed on the great estates of southern Italy.

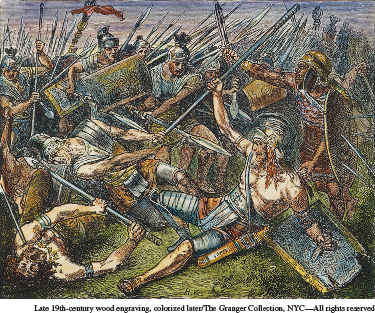

Roman authorities became increasingly concerned when Spartacus and his followers began to manufacture their own weapons and to organize into a more coherent military force, which defeated in turn several hurriedly assembled Roman armies and plundered the rich farming region of Campania. The fortunes of the rebels peaked in 72 B.C.E. when they briefly threatened Rome itself. Both sides treated their opponents brutally. The Greek historian Appian reported that Spartacus ordered the sacrifice of 300 Roman prisoners in honor of the slain rebel leader Crixus, while another historian claimed that Spartacus staged gladiatorial games using 400 captives. When the revolt was finally suppressed, captured rebel slaves received similarly brutal treatment from the Roman authorities.

Fearful for the safety of the capital, the Roman authorities acted decisively. They appointed Marcus Licinius Crassus, a rich and ambitious Roman aristocrat and military commander, to lead eight Roman legions, totaling perhaps 40,000 troops, against Spartacus and his rebels. Crassus cornered the slave army in the far south of Italy, and Spartacus soon realized that his followers faced a fight to the death. According to the historian Appian, he advertised their precarious situation to his troops by crucifying a Roman soldier “as a visual reminder to his own men of what would happen to them if they did not win.”15 Rather than be captured, Spartacus and the slaves with him chose to make a last stand. The Greek historian Plutarch reports that Spartacus killed his horse in front of his troops to show that he had no intention of fleeing, and led his forces in a final desperate engagement with Crassus’s army. Even the most hostile of later historians recounted that Spartacus died bravely during the battle, even if some claimed that his body was never found. For those that survived, a terrible vengeance followed as some 6,000 captured rebel slaves were nailed to crosses along the Appian Way, between Capua, where the rebellion began, and Rome. These crucified prisoners, spaced some thirty-five to forty yards apart for over a hundred miles, provided a clear warning to all others who contemplated rebellion.

Spartacus’s revolt had little lasting effect on the society in which he lived. No further large-scale revolts took place in the Roman Empire, and Rome continued its economic system based on slave labor. Moreover, the rebellion occasioned little historical comment until the eighteenth century. However, over the past two and a half centuries, a number of groups have embraced Spartacus, casting him as an inspirational leader of the downtrodden who resisted injustice and subjugation. Marxists, socialists, and nationalists have all found something to admire in Spartacus and his rebellion. In the United States, Spartacus entered the popular imagination due in no small part to the success of the 1960 epic film Spartacus, starring Kirk Douglas as the rebel leader fighting against the odds to free the oppressed. While there is no historical evidence that Spartacus ever intended to abolish slavery or fundamentally reform Roman society, in modern times his heroic, if ultimately failed, quest for freedom has been recovered from the past, becoming for many an inspirational symbol of just resistance to oppression. In such ways, the past continues to resonate in the present.

Questions: What can Spartacus’s revolt tell us about the nature of the slave system in the Roman Empire? How might you account for the renewed interest in Spartacus over the past two and a half centuries?