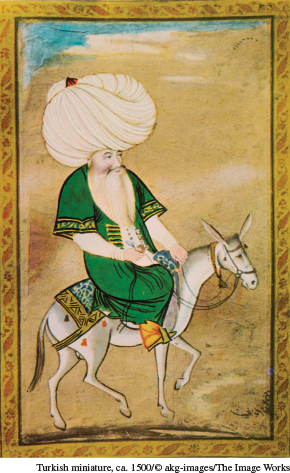

Mullah Nasruddin, the Wise Fool of Islam

I n the Islamic world, a mullah was a man of some learning, often a local cleric or leader of a village mosque. Far and away the most famous and beloved of mullahs is Nasruddin, considered both a wise man and a fool, both a sage and a simpleton. Stories about him have circulated for centuries and were well known long before the earliest written references to him appeared in the thirteenth century. Many peoples have claimed him, some have sought to find a historical figure on which he is based, and in the Turkish city of Aksehir there is even a tomb and an annual Nasruddin festival, where people dress in costumes to reenact his jokes and stories.

In fact, Mullah Nasruddin has long been an imaginary folk character within the world of Islam and especially among Sufis, gently expressing a skeptical attitude toward the rational mind, sanctimonious posturing, human vanity, and the many faces of the ego. His tales usually take place in a village setting and highlight the limitations of the intellect; the role of humor and intuition in spiritual life; the importance of generosity, tolerance, and humility; and the many mysteries of existence. The only way to get acquainted with Mullah Nasruddin is to reflect on some of his tales. Here are just a few of the thousands:13

The Mullah was in Mecca for the pilgrimage and had fallen asleep with his feet pointing toward the Kaaba, the large black cube that is the central shrine of Islam. He was awakened and rebuked by some pious Muslims, who told him it was offensive to have his dirty feet pointing at the Kaaba, where God himself resided. The Mullah apologized profusely and then added, “Perhaps you could move my feet to some place where God is not present.”

Mullah Nasruddin was invited to a formal reception and upon entering took the seat of greatest honor. Approached by the chief of the guard, he was asked if he was a diplomat, a minister of the king, or perhaps the king himself in disguise. To each of these queries, he replied, “No, I am more than that.” “Then who are you?” demanded the guard. His answer: “I am nobody.”

A villager rushed to tell the Mullah about visions of God he had been having. He asked if this meant he had become enlightened. The Mullah replied by asking him about his goats and servants. The man was enraged at this apparent dismissal of his visions. Then the Mullah explained, “If you are becoming more tender and kind toward your goats and servants, then you are on the way to enlightenment. If not, your visions are an illusion of your ego.”

Mullah Nasruddin was asked to present a lecture on “the nature of Allah” in the local mosque together with many highly learned scholars. When the scholars had finished their eloquent and wise expositions, the humble Mullah arose and hesitantly began his talk by declaring “Allah is an eggplant,” while holding one of the vegetables aloft. An uproar followed at this blasphemy. When he was finally given a chance to explain himself, the Mullah declared, “Everyone before me has spoken of what they do not know or have never seen. But we can all see this eggplant. Can anyone deny that Allah is manifest in all things?” When no one was willing to dispute the point, the Mullah concluded, “Well, then Allah is an eggplant.”

One evening, after spending many hours in the local tavern, a thoroughly intoxicated Mullah was stumbling along the streets. A local police official approached him and asked, “Who are you? Where did you come from? Where are you going? Why are you out so late?” The Mullah replied, “If I had answers to all those questions, I’d be home already.” [Note: To Sufis, taverns and drunkenness often symbolized spiritual insight or mystical “intoxication” with the Divine.]

When some neighbors told Nasruddin that his donkey was lost, the Mullah exclaimed, “Thank goodness I was not on the donkey or I’d be lost as well.” [Note: In Sufi circles, the donkey has long symbolized the unruly human ego.]

The Mullah’s tales have been understood on several levels. Most obviously, they are jokes. But they also convey moral teachings about individual behavior as well as social commentary. And especially for Sufis, they have become a spiritual resource, gradually dissolving limited and culturally conditioned thinking, while opening the way to more fully realizing humanity’s divine potential.

Questions: Pick several of these tales and explain in your own words the lessons they might convey for Muslims. In what ways might these tales be considered subversive of established authorities? Might they strike a chord with contemporary sensibilities of our own time?