Writing about What Haunts Us, Peter Orner

READING

Writing about What Haunts Us

Peter Orner

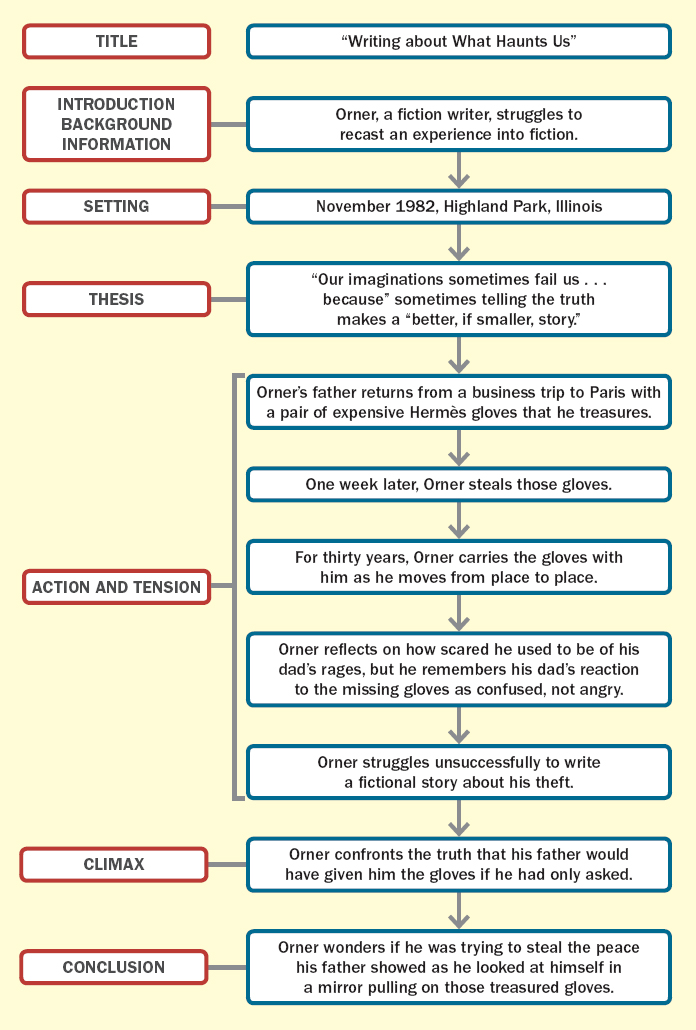

Peter Orner is an award-winning author and essayist whose works have appeared in numerous publications, including The Southern Review, The Atlantic Monthly, and The New York Times. He is the author of two novels: Love and Shame and Love (2011) and The Second Coming of Mavala Shikongo (2006). Born in Chicago, Orner now lives in California, where he is a professor of creative writing at San Francisco State University. This memoir appeared in The New York Times online in January 2013. Figure 12.2, a graphic organizer for “Writing about What Haunts Us,” appears below. Read the narrative first, and then study the graphic organizer.

I’ve been trying to lie about this story for years. As a fiction writer, I feel an almost righteous obligation to the untruth. Fabrication is my livelihood, and so telling something straight, for me, is the mark of failure. Yet in many attempts over the years I’ve not been able to make out of this tiny — but weirdly soul-defining — episode in my life anything more than a plain recounting of the facts, as best as I can remember them. Dressing them up into fiction, in this case, wrecked what is essentially a long overdue confession.

1

Here’s the nonfiction version.

2

I watched my father in the front hall putting on his new, lambskin leather gloves. It was a sort of private ceremony. This was in early November, 1982, in Highland Park, Ill., a town north of Chicago along Lake Michigan. My father had just returned from a business trip to Paris. He’d bought the gloves at a place called Hermès, a mythical wonderland of a store. He pulled one on slowly, then the other, and held them up in the mirror to see how his hands looked in such gloves.

3

A week later, I stole them.

4

I remember the day. I was home from school. Nobody else was around. I opened the left-hand drawer of the front hall table and there they were. I learned for the first time how easy it is to just grab something. I stuffed the gloves in my pants and sprinted upstairs to my room. I hid them in the back of my closet under the wicker basket that held my license plate collection. Then I braced myself, for days. It was a warm November.

5

When we finally left that house — my mother, my brother and me — I took the gloves with me to our new place. I took them with me to college. To Boston, to Cincinnati, to North Carolina, to California. I even took them with me to Namibia for two years. I have them now, on my desk, 30 years later.

6

I’ve never worn them, not once, although my father and I have the same small hands. I didn’t want the gloves. I never wanted the gloves. I only wanted my father not to have them.

7

Now that he is older and far milder, it is hard to believe how scared I used to be of my father. Back then he was so full of anger. Was he unhappy in his marriage? No doubt. He and my mother never had much in common. But his anger — sometimes it was rage — went beyond this not so unusual disappointment. My own totally unscientific, armchair diagnosis is that like other chronically unsatisfied people, the daily business of living caused my father despair. At no time did this manifest itself more powerfully than when he came home from work. A rug askew, a jacket not hung up, a window left open — all could set off a fury. My brother once spilled a pot of ink on the snowy white carpet of my parents’ bedroom: Armageddon.

8

His unpredictability is what made his explosions so potent. Sometimes the bomb wouldn’t go off, and he’d act like my idea of a normal dad. When he finally noticed those precious gloves were missing, he seemed only confused.

9

“Maybe they’re in the glove compartment,” my mother said.

10

“Impossible. I never put gloves in the glove compartment. The glove compartment is for maps.”

11

“Oh, well,” my mother said.

12

He kept searching the front hall table, as if he had somehow overlooked them amid all the cheap imitation leather gloves, mismatched mittens and tasseled Bears hats. I am certain the notion that one of us had taken the gloves never crossed his mind.

13

Haunted by my guilt, a frequent motivation for my fiction in general, I’ve tried to contort my theft into a story, a made-up story.

14

In my failed attempts, the thief is always trying to give the gloves back. In one abandoned version, the son character (sometimes he’s a daughter) mails the gloves back to the father, along with a forged letter, purportedly written by a long-dead friend of the father, a man the father had once betrayed. I liked the idea of a package arriving, out of the blue, from an aggrieved ghost. I’m returning your gloves, Phil. Now at least one of us may be absolved.

15

The problem was that it palmed off responsibility on a third party. And it muddied the story by pulling the thief out of the center of what little action there was.

16

In a simpler but equally bad version, the son character, home for Thanksgiving, slips the gloves back in the top left-hand drawer of the front hall table of the house he grew up in, the house where the father still lives. This attempt was marred not only by cooked-up dialogue but also by a dead end.

17

“Dad! How about we take a walk by the lake?”

18

“It’s been years, Son, since we’ve taken a walk.”

19

“Pretty brisk out. Maybe you need your gloves?”

20

The moment arrives: the father slides open the drawer. Voilà! (Note the French.) Cut to the father’s face. Describe his bewilderment. I must have checked this drawer a hundred thousand times. Decades drop from the father’s eyes, and both father and son face each other as they never faced each other when both were years younger. The son stammers out a confession I could somehow never get right. He tries to explain himself, but can’t. Why did he take the gloves? My character could never express it in words and the story kept collapsing.

21

This is where the truth of this always derails the fiction. I can’t give the gloves back, in fiction or in this thing we call reality. If I did, I’d have to confront something I’ve known all along but have never wanted to express, even to myself alone. My father would have given me his gloves. All I had to do was ask. He would have been so pleased that for once we shared a common interest. This happened so few times in our lives. All the years I’ve been trying to write this, maybe I’ve always known that this essential fact would stick me in the heart.

22

Our imaginations sometimes fail us for a reason. Not because it is cathartic to tell the truth (I finally told my father last year) but because coming clean may also be a better, if smaller, story. A scared (and angry) kid rips off his father’s gloves, carries them around for decades. Sometimes he takes them out and feels them but never puts them on. When I see my father these days, we graze each other’s cheeks, a form of kissing in my family. I love my father. I suppose I did even then, in the worst moments of fear.

23

Well-made things eventually deteriorate. The Hermès gloves are no longer baby-soft. All the handless years have dried them up.

24

In 1982, my father wasn’t much older than I am at this moment. I think of him now, standing in the front hall. He’s holding his hands up in the mirror, pulling on his beautiful gloves, a rare stillness on his face, a kind of hopeful calm. Was this what I wanted to steal?

25