|

|

Select a topic from the list above, or create your own. Use one or more of the following suggestions to generate topic ideas.

- Peruse your textbooks, looking for boldfaced terms that you find interesting or want to learn about. List several and then, alone or with another student, brainstorm examples that would help to illustrate or explain the concept. You may need to read your textbook for models. (If you are an abstract thinker, starting from a generalization and then coming up with examples may work better for you.)

- Work backward: Make a list of the things you do for fun or find challenging and then consider what they have in common. Use that common thread as your topic.

After you have chosen your topic, make sure that you can develop your main idea into a well-focused working thesis. |

Consider your purpose, audience, and point of view. Ask yourself these questions.

- Will my essay’s purpose be to express myself, inform, or persuade? Several examples may be needed to persuade. One extended example may be sufficient to inform readers about a very narrow topic (for example, how to select an educational toy for a child).

- Who is my audience? Will readers need any background information to understand my essay? What types of examples will be most effective with these readers? Straightforward examples, based on everyday experience, may be appropriate for an audience unfamiliar with your topic; more technical examples may be appropriate for an expert audience.

- What other evidence (such as facts and statistics, expert opinion) will I need to make my case with my audience? Do I have enough information to write about this topic, or must I consult additional sources? How might I use additional patterns of development within my illustration essay? (For example, you might use narration to present an extended example from your own life.)

- What point of view best suits my purpose and audience? (Unless the examples you use are all drawn from your personal experience, you will probably use the third person when using examples to explain.)

|

Narrow your topic and generate examples. Narrow your topic. Use prewriting to make your topic manageable. Be sure you can support your topic with one or more examples. Use idea-generating strategies to come up with a wide variety of examples.

- Write down the generalizations your essay will make, and then brainstorm examples that support them.

- Freewrite to bring to mind relevant personal experiences or stories told by friends and relatives.

- Conduct research to find examples used by experts and relevant news reports and to locate other supporting information, like facts and statistics.

- Review textbooks for examples used there.

Creative and abstract learners may have trouble focusing on details. If you have trouble, try teaming up with a classmate who has a pragmatic or concrete learning style for help. Hint: Keep track of where you found each example so that you can cite your sources accurately. |

Try these suggestions to help you evaluate your examples.

- Reread everything you have written. (Sometimes reading your notes aloud is helpful.)

- Highlight examples that are representative (or typical) yet striking. Make sure they are relevant (they clearly illustrate your point). Unless you are using just one extended example, make sure your examples are varied. Then copy and paste the usable ideas to a new document to consult while drafting.

- Collaborate. In small groups, take turns giving examples and having classmates tell you . . .

- what they think your main idea is. (If they don’t get it, rethink your examples.)

- what additional information they need to find your main idea convincing.

Classmates can also help narrow your topic or think of more effective examples. |

|

Draft your thesis statement. Try one or more of the following strategies to develop a generalization that your examples support. (Your generalization will become your working thesis.)

- Systematically review your examples asking yourself what they have in common.

- Discuss your thesis with a classmate. Do the examples support the thesis? If not, try to improve on each other’s examples or revise the thesis.

- In a two-column list, write words in the left column describing how you feel about your narrowed topic. (For example, the topic cheating on college exams might generate such feelings as anger, surprise, and confusion.) In the right column, add details about specific situations in which these feelings arose. (For example, your thesis might focus on your surprise on discovering that a good friend cheated on an exam.)

- Research your topic in the library or on the Internet to uncover examples outside your own experience. Then ask yourself what the examples from your experience and your research have in common.

Note: As you draft, you may think of situations or examples that illustrate a different or more interesting thesis. Don’t hesitate to revise your thesis as you discover more about your topic. Collaborate with classmates to make sure your examples support your thesis statement. |

Select a method of organization.

- If you are using a single, extended example, you are most likely to use chronological order to relate events in the sequence in which they happened.

- If you are using several examples, you are most likely to organize the examples from most to least or least to most important.

- If you are using many examples, you may want to group them into categories. For instance, in an essay about the use of slang, you might classify examples according to regions or age groups in which they are used.

Hint: An outline or graphic organizer will allow you to experiment to find the best order for supporting paragraphs. (Spatial learners may prefer to draw a graphic organizer, while verbal learners may prefer to write an outline.) |

Write a first draft of your illustration essay. Use the following guidelines to keep your illustration essay on track.

- The introduction should spark readers’ interest and include background information (if needed by readers). Most illustration essays include a thesis near the beginning to help readers understand the point of upcoming examples.

- The body paragraphs should include topic sentences to focus each paragraph (or paragraph cluster) on one key idea. Craft one or more examples for each paragraph (or cluster) to illustrate that key idea. Use vivid descriptive language to make readers feel as if they are experiencing or observing the situation. Include transitions, such as for example or in particular, to guide readers from one example to another. (Consult Chapter 8 for help with crafting effective descriptions.)

- The conclusion should include a final statement that pulls together your ideas and reminds readers of your thesis.

|

|

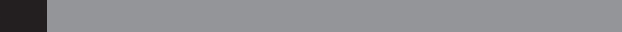

Evaluate your draft, and revise as necessary. Use Figure 14.3, “Flowchart for Revising an Illustration Essay,” to evaluate and revise your draft. |

|

Edit and proofread your essay.

- editing sentences to avoid wordiness, making your verb choices strong and active, and making your sentences clear, varied, and parallel, and

- editing words for tone and diction, connotation, and concrete and specific language.

Pay particular attention to the following:

- Keep verb tenses consistent in your extended examples. When using an event from the past as an example, however, always use the past tense to describe it.

Example: Special events are an important part of children’s lives. Parent visitation day at school was an event my daughter talked about for an entire week. Children are also excited by . . .

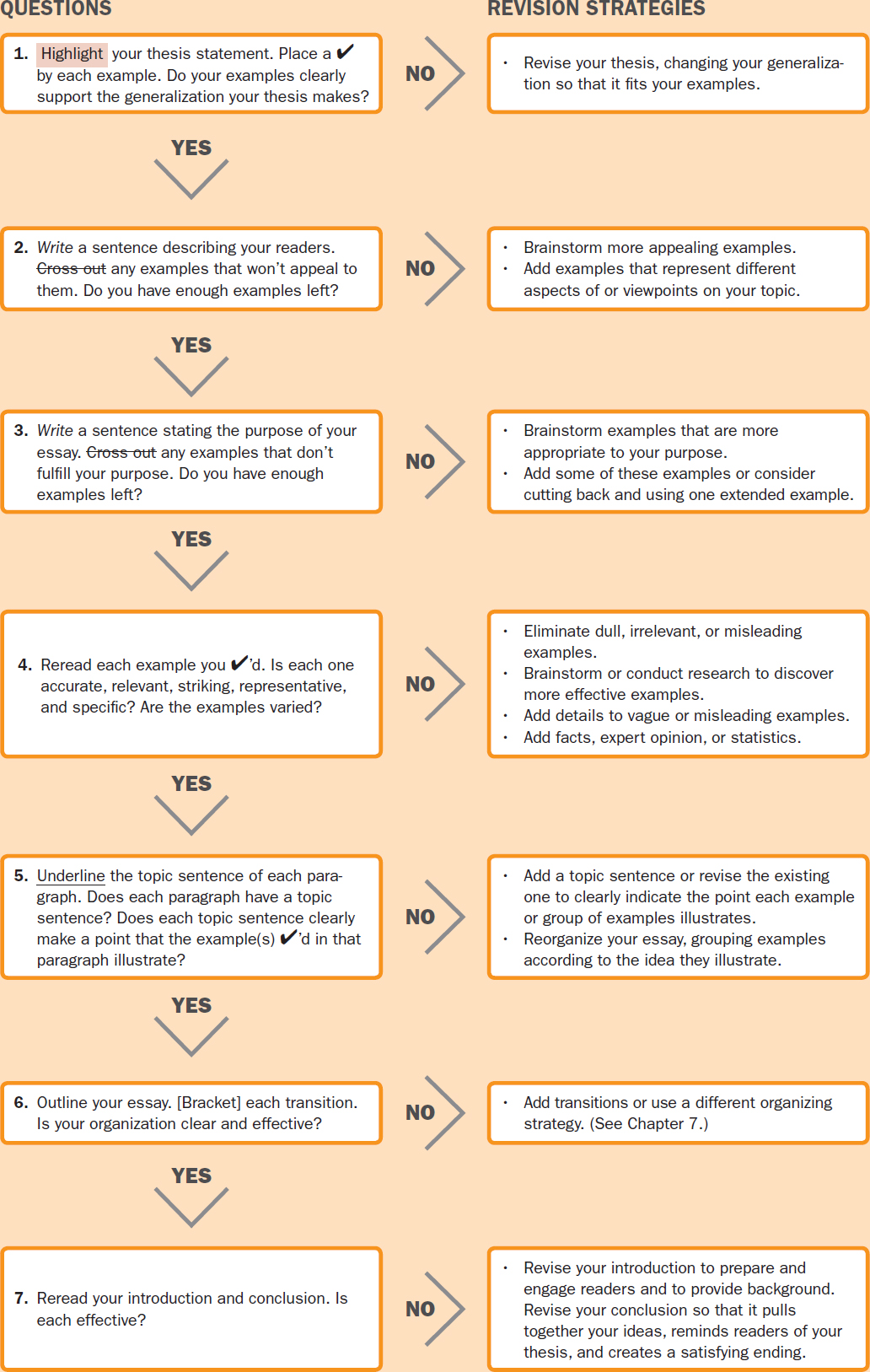

- Use first person (I, me, we, us), second person (you), or third person (he, she, it, him, her, they, them) consistently.

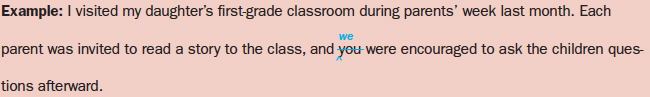

- Avoid sentence fragments when introducing examples. Each sentence must have both a subject and a verb.

|