“Dude, Do You Know What You Just Said?” Mike Crissey

READING

Dude, Do You Know What You Just Said?

MIKE CRISSEY

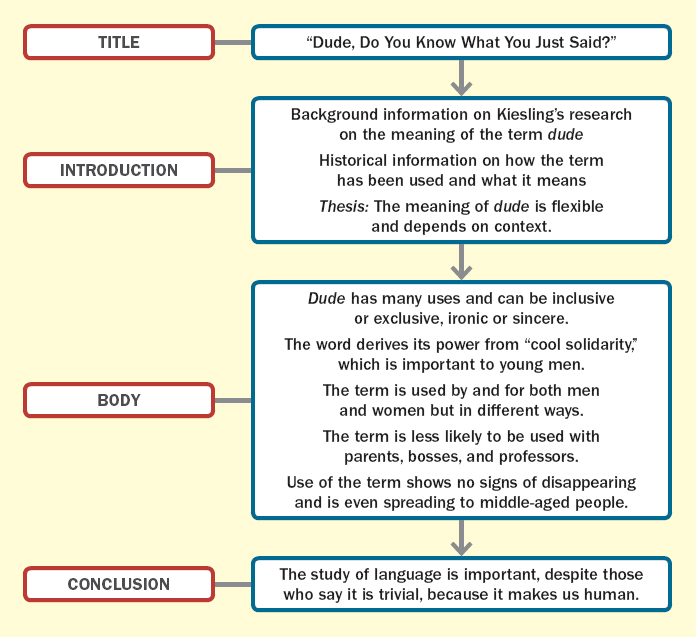

Mike Crissey is a staff writer for the Associated Press. The following article, which appeared in The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette on December 8, 2004, is based on research done by Scott Kiesling, a professor of linguistics at the University of Pittsburgh. Kiesling’s work focuses on the relationship between language and identity, particularly in the contexts of gender, ethnicity, and class. As you read, notice how the writer uses a combination of expert testimony, anecdotal evidence, and personal observations to support his main point.

Dude, you’ve got to read this. A University of Pittsburgh linguist has published a scholarly paper deconstructing and deciphering dude, the bane of parents and teachers, which has become as universal as like and another vulgar four-letter favorite. In his paper in the fall edition of the journal American Speech, Scott Kiesling says dude is much more than a greeting or catchall for lazy, inarticulate, and inexpressive (and mostly male) surfers, skaters, slackers, druggies, or teenagers. “Without context there is no single meaning that dude encodes and it can be used, it seems, in almost any kind of situation. But we should not confuse flexibility with meaninglessness,” Kiesling said.

1

Originally meaning “old rags,” a “dudesman” was a scarecrow. In the late 1800s, a “dude” was akin to a dandy, a meticulously dressed man, especially in the western United States. Dude became a slang term in the 1930s and 1940s among black zoot suiters and Mexican American pachucos. The term began its rise in the teenage lexicon with the 1982 movie Fast Times at Ridgemont High. Around the same time, it became an exclamation as well as a noun. Pronunciation purists say it should sound like “duhd”; “dood” is an alternative, but it is considered “uncool” or old.

2

To decode dude, Kiesling listened to conversations with fraternity members he taped in 1993 and had undergraduate students in sociolinguistics classes in 2001 and 2002 write down the first twenty times they heard dude and who said it during a three-day period. He’s also a lapsed dude-user who during his college years tried to talk like Jeff Spicoli, the slacker surfer “dude” from Fast Times at Ridgemont High.

3

According to Kiesling, dude has many uses: an exclamation (“Dude!” and “Whoa, Dude!”); to one-up someone (“That’s so lame, dude”); to disarm confrontation (“Dude, this is so boring”), or simply to agree (“Dude”). It’s inclusive or exclusive, ironic or sincere.

4

Kiesling says dude derives its power from something he calls cool solidarity: an effortless or seemingly lazy kinship that’s not too intimate; close, dude, but not that close. Dude “carries . . . both solidarity (camaraderie) and distance (non-intimacy) and can be deployed to create both of these kinds of stance, separately or together,” Kiesling wrote. Kiesling, whose research focuses on language and masculinity, said that cool solidarity is especially important to young men — anecdotally the predominant dude-users — who are under social pressure to be close with other young men but not enough to be suspected as gay. “It’s like man or buddy. There is often this male-male addressed term that says, ‘I’m your friend but not much more than your friend,’” Kiesling said. Aside from its duality, dude also taps into nonconformity, despite everyone using it, and a new American image of leisurely success, he said.

5

The nonchalant attitude of dude also means that women sometimes call each other dudes. And less frequently, men will call women dudes and vice versa, Kiesling said. But that comes with some rules, according to self-reporting from students in a 2002 language and gender class at the University of Pittsburgh included in his paper. “Men report that they use dude with women with whom they are close friends, but not with women with whom they are intimate,” according to his study.

6

His students also reported that they were least likely to use the word with parents, bosses, and professors. “It is not who they are but what your relationship is with them. With your parents, you likely have a close relationship, but unless you’re Bart Simpson, you’re not going to call your parent dude,” Kiesling said. “There are a couple of young professors here in their thirties and every once in a while we use dude. Professors are dudes, but most of the time they are not.”

7

And dude shows no signs of disappearing. “More and more our culture is becoming youth centered. In southern California, youth is valued to the point that even active seniors are dressing young and talking youth,” said Mary Bucholtz, an associate professor of linguistics at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “I have seen middle-aged men using dude with each other.”

8

So what’s the point, dude? Kiesling and linguists argue that language and how we use it is important. “These things that seem frivolous are serious because we are always doing it. We need to understand language because it is what makes us human. That’s my defense of studying dude,” Kiesling said.

9