“How Labels Like Black and Working Class Shape Your Identity,” Adam Alter

READING

How Labels Like Black and Working Class Shape Your Identity

ADAM ALTER

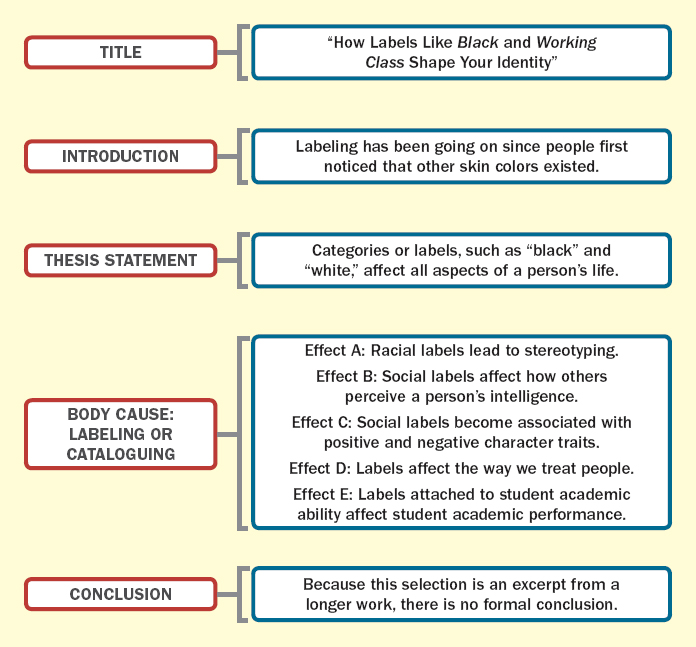

Adam Alter is an assistant professor of marketing and psychology at New York University. His research focuses on decision making, and he has published numerous articles in academic journals in psychology. He has also published a number of articles for general readers in publications such as The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Psychology Today. This reading is from Alter’s 2013 book Drunk Tank Pink and Other Unexpected Forces That Shape How We Think, Feel, and Behave. Figure 19.4, a graphic organizer for “How Labels Like Black and Working Class Shape Your Identity,” appears below. Before studying that graphic organizer, read this causal analysis essay and highlight the effects that Alter names as resulting from racial and/or social labeling.

Long ago, humans began labeling and cataloguing each other. Eventually, lighter-skinned humans became “whites,” darker-skinned humans became “blacks,” and people with intermediate skin tones became “yellow-,” “red-,” and “brown-skinned.” These labels don’t reflect reality faithfully, and if you lined up 1,000 randomly selected people from across the earth, none of them would share exactly the same skin tone. Of course, the continuity of skin tone hasn’t stopped humans from assigning each other to discrete categories like “black” and “white” — categories that have no basis in biology but nonetheless go on to determine the social, political, and economic well-being of their members.

1

Social labels aren’t born dangerous. There’s nothing inherently problematic about labeling a person “right-handed” or “black” or “working class,” but those labels are harmful to the extent that they become associated with meaningful character traits. At one end of the spectrum, the label “right-handed” is relatively free of meaning. We don’t have strong stereotypes about right-handed people, and calling someone right-handed isn’t tantamount to calling them unfriendly or unintelligent.

2

In contrast, the terms “black” and “working class” are laden with the baggage of associations, perhaps some of them positive, but many of them negative. During the height of the civil-rights struggle, one teacher showed just how willingly children adopt new labels. On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered, and the next day thousands of American children went to school with a combination of misinformation and confusion. In Riceville, Iowa, Stephen Armstrong asked his teacher, Jane Elliott, why “they shot that king.” Elliott explained that the “king” was a man named King who was fighting against the discrimination of “Negroes.” The class of white students was confused, so Elliott offered to show them what it might be like to experience discrimination themselves.

3

Elliott began by claiming that the blue-eyed children were better than the brown-eyed children. The children resisted at first. The brown-eyed majority was forced to confront the possibility that they were inferior, and the blue-eyed minority faced a crisis when they realized that some of their closest friendships were now forbidden. Elliott explained that the brown-eyed children had too much melanin, a substance that darkens the eyes and makes people less intelligent. Melanin caused the “brownies,” as Elliott labeled them, to be clumsy and lazy. Elliott asked the brownies to wear paper armbands — a deliberate reference to the yellow armbands that Jews were forced to wear during the Holocaust. Elliott reinforced the distinction by telling the brown-eyed children not to drink directly from the water fountain, as they might contaminate the blue-eyed children. Instead, the brownies were forced to drink from paper cups. Elliott also praised the blue-eyed children and offered them privileges, like a longer lunch break, while she criticized the brown-eyed children and forced them to end lunch early. By the end of the day, the blue-eyed children had become rude and unpleasant toward their classmates, while even the gregarious brown-eyed children were noticeably timid and subservient.

4

News of Elliott’s demonstration traveled quickly, and she was interviewed by Johnny Carson. The interview lasted a few brief minutes, but its effects persist today. Elliott was pilloried by angry white viewers across the country. One angry white viewer scolded Elliott for exposing white children to the discrimination that black children face every day. Black children were accustomed to the experience, the viewer argued, but white children were fragile and might be scarred long after the demonstration ended. Elliott responded sharply by asking why we’re so concerned about white children who experience this sort of treatment for a single day, while ignoring the pain of black children who experience the same treatment across their entire lives. Years later, Elliott’s technique has been used in hundreds of classrooms and in workplace-discrimination training courses, where adults experience similar epiphanies. Elliott’s approach shows how profoundly labels shape our treatment of other people and how even arbitrary damaging labels have the power to turn the brightest people into meek shadows of their potential selves.

5

Four years before Jane Elliott’s classroom demonstration, two psychologists began a remarkable experiment at a school in San Francisco. Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson set out to show that the recipe for academic achievement contains more than raw intellect and a dozen years of schooling. Rosenthal and Jacobson kept the details of the experiment hidden from the teachers, students, and parents; instead, they told the teachers that their test was designed to identify which students would improve academically over the coming year — students they labeled “academic bloomers.” In truth, the test was an IQ measure with separate versions for each school grade, and it had nothing to do with academic blooming. As with any IQ test, some of the students scored quite well, some scored poorly, and many performed at the level expected from students of their age group.

6

The next phase of the experiment was both brilliant and controversial. Rosenthal and Jacobson recorded the students’ scores on the test, and then labeled a randomly chosen sample of the students as “academic bloomers.” The bloomers performed no differently from the other students — both groups had the same average IQ score — but their teachers were told to expect the bloomers to experience a rapid period of intellectual development during the following year.

7

When the new school year arrived, each teacher watched as a new crop of children filled the classroom. The teachers knew very little about each student, except whether they had been described as bloomers three months earlier. As they were chosen arbitrarily, the bloomers should have fared no differently from the remaining students. The students completed another year of school and, just before the year ended, Rosenthal and Jacobson administered the IQ test again. The results were remarkable.

8

The first and second graders who were labeled bloomers outperformed their peers by 10–15 IQ points. Four of every five bloomers experienced at least a 10-point improvement, but only half the non-bloomers improved their score by 10 points or more. Rosenthal and Jacobson had intervened to elevate a randomly chosen group of students above their relatively unlucky peers. Their intervention was limited to labeling the chosen students “bloomers,” and remaining silent on the academic prospects of the overlooked majority.

9

Observers were stunned by these results, wondering how a simple label could elevate a child’s IQ score a year later. When the teachers interacted with the “bloomers,” they were primed to see academic progress. Each time a bloomer answered a question correctly, her answer seemed to be an early sign of academic achievement. Each time she answered a question incorrectly, her error was seen as an anomaly, swamped by the general sense that she was in the process of blooming.

10

During the year, then, the teachers praised these students for their successes, overlooked their failures, and devoted plenty of time and energy to the task of ensuring that they would grow to justify their promising academic labels. The label “bloomer” did not just resolve ambiguity, in other words — it changed the outcome for those students.

11