THE BASIC PARTS OF AN ARGUMENT

In everyday conversation, an argument can be a heated exchange of ideas between two people. College roommates might argue over who should clean the sink or who left the door unlocked the previous night. Colleagues in a company might argue over policies or procedures. However, there is a difference between an emotional, irrational argument and a rational, effective argument.

An effective argument is a logical, well-thought-out presentation of ideas that makes a claim about an issue and supports that claim with evidence. This does not mean that emotion has no place in an argument. In fact, many sound arguments combine emotion with logic.

Even a casual conversation can make a reasoned argument, as in the following.

| Damon: | I’ve been called for jury duty. I don’t want to go. They treat jurors so badly! |

| Maria: | Why? Everybody is supposed to do it. |

| Damon: | Have you ever done it? I have. First of all, they force us to serve, whether we want to or not. And then they treat us like criminals. Two years ago I had to sit all day in a hot, crowded room with other jurors while the TV was blaring. I couldn’t read, study, or even think! No wonder people will do anything to get out of it. |

Damon is arguing that jurors are treated badly. He offers two reasons to support his claim and uses personal experience to support the second reason (that jurors are treated “like criminals”), which also serves as an emotional appeal.

An effective argument must clearly state an issue, make a claim, and offer support. In many cases an argument also recognizes or refutes (argues against) opposing viewpoints.

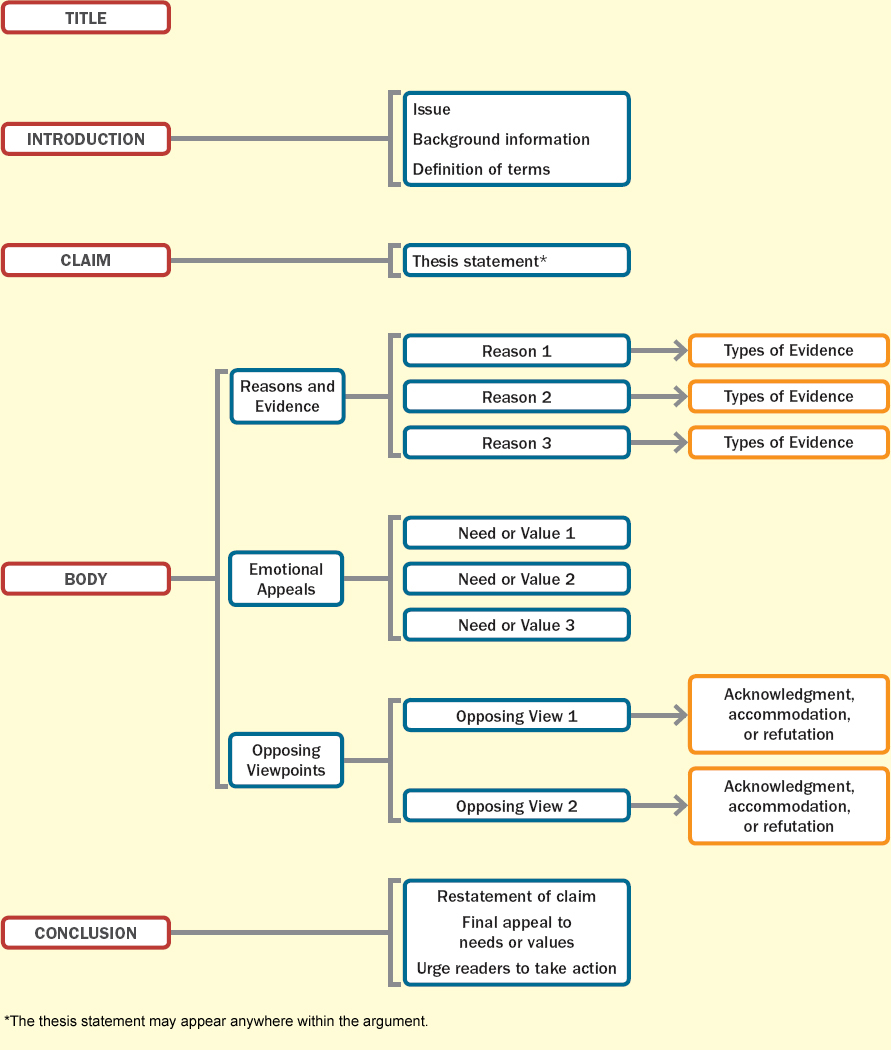

A graphic organizer showing the basic components of an argument appears in Figure 20.1. Note that unlike the graphic organizers in Chapters 11-19, the model graphic organizer that follows does not necessarily reflect the order in which the ideas are presented. Rather, it provides a visual representation of the components of an argument. The arguments you read may address opposing views before presenting reasons and evidence in support of the writer’s claim, for example.

THE ISSUE

An argument is concerned with an issue — a controversy, a problem, or an idea about which people hold different points of view. In the exchange between Damon and Maria, the issue is “fairness of jury duty.”

THE CLAIM

The claim is the point the writer tries to prove, usually the writer’s view on the issue. In Damon and Maria’s conversation, the claim is that “jury duty is unfair.” The claim often appears as part of the thesis statement in an argument essay. In some essays, however, it is implied rather than stated directly.

There are three types of claims.

- Claims of fact are statements that can be proved or verified. Of course, readers are not likely to be interested in arguments about long-established claims of fact, such as how far the moon is from the earth; instead, claims of fact in argument essays focus on facts that are in dispute or not yet well established.

EXAMPLE Global warming has taken a serious toll on the environment. - Claims of value are statements that express an opinion or judgment about whether one thing or idea is better or more desirable than other things or ideas. Issues involving questions of right or wrong, acceptable or unacceptable, often lead to claims of value. Since claims of value are subjective, they cannot be proved definitively.

EXAMPLE Doctor-assisted suicide is a violation of the Hippocratic oath and therefore should not be legalized. - Claims of policy are statements offering one or more solutions to a problem. Often the verbs should, must, or ought appear in the claim. Like claims of value, claims of policy cannot be proved definitively.

EXAMPLE The motion picture industry must accept greater responsibility for the consequences of violent films.

THE SUPPORT

The support in an argument consists of the ideas and information intended to convince readers that the claim is sound or believable. In Damon and Maria’s conversation, Damon provides two key pieces of support.

- People are forced to serve.

- Potential jurors are treated like criminals.

Three common types of support are reasons, evidence, and emotional appeals.

Reasons. A reason is a general statement that backs up a claim. It explains why the writer’s view on an issue is reasonable or correct. However, reasons alone are not sufficient support for an argument. Each reason must be supported by evidence and is sometimes accompanied by emotional appeals.

Evidence. The evidence provided in an argument usually consists of facts, statistics, examples, expert opinion, and observations from personal experience.

| CLAIM | Reading aloud to preschool and kindergarten children improves their chances of success in school. |

| FACTS | First-grade children who were read to as preschoolers learned to read earlier than children who were not read to. |

| STATISTICS | A 1998 study by Robbins and Ehri demonstrated that reading aloud to children produced a 16 percent improvement in the children’s ability to recognize words used in a story. |

| EXPERT OPINION | Pam Allyn, author of over sixty educational publications and well-known childhood literacy advocate urges parents to read aloud to their preschool children frequently. |

| EXAMPLES | Stories about unfamiliar places or activities increase a child’s vocabulary. For example, reading a story about a farm to a child who lives in a city apartment will acquaint the child with such new terms as barn, silo, and tractor. |

| PERSONAL EXPERIENCE | When I read to my three-year-old son, I notice that he points to and tries to repeat words. |

Emotional appeals. Emotional appeals evoke the needs or values that readers are likely to share.

- Appealing to needs: People have both physiological needs (food and drink, health, shelter, safety, sex) and psychological needs (a sense of belonging or accomplishment, self-esteem, recognition by others, self-fulfillment). Your friends and family, people who write letters to the editor, personnel directors who write job listings, and advertisers all appeal to needs, directly or indirectly.

- Appealing to values: A value is a principle or quality that is considered important, worthwhile, or desirable, such as freedom, justice, loyalty, friendship, patriotism, duty, and equality. Arguments often appeal to values that the writer assumes most readers will share.

The public service announcement appeals to both viewers’ needs and values. The picture of the cute dog appeals to viewers’ needs by evoking the emotional attachment to companion animals (either our own or other people’s pets) that many of us share. The text, “a person is the best thing to happen to a shelter pet,” also appeals to viewers’ need to be needed. The ad appeals to values as well by evoking the principle that caring for others, including animals, is important.

REFUTATION

A refutation, also called a rebuttal, recognizes and argues against opposing viewpoints. Refutation involves finding a weakness in the opponent’s argument by casting doubt on the opponent’s reasons or by questioning the accuracy, relevance, and sufficiency of the opponent’s evidence.

Suppose you want to argue that you deserve a raise at work (your claim). To support your claim, you will remind your supervisor of the contributions and improvements you have made, your length of employment, your conscientiousness, and your promptness. But you suspect that your supervisor may still turn you down, not because you don’t deserve the raise but because other employees might demand a similar raise. By anticipating this potential objection, you can build into your argument the reasons that the objection is not valid. You may have more time invested with the company and have taken on more responsibilities than the other employees, for example.

If an opponent’s argument is too strong to refute, most writers will acknowledge or accommodate the opposing viewpoint in some way. They acknowledge an opposing view simply by stating it. They accommodate an opposing view by noting that it has merit and modifying their position or finding a way of addressing it. In an argument opposing hunting, for example, a writer might simply acknowledge the view that hunting bans would cause a population explosion among deer. The writer might accommodate this opposing view by stating that if a population explosion were to occur, the problem could be solved by reintroducing natural predators into the area.

The following readings illustrate the components of effective argument essays. The first reading is annotated to point out those components. As you read the second essay, try to identify for yourself the claim and the supporting reasons, evidence, and emotional appeals Brian Palmer includes. Look, too, for places where Palmer refutes, accommodates, or acknowledges opposing views on tipping.