CONSIDERING SOURCE TYPES

Once you have a working thesis and a list of research questions, stop for a moment. Think about which kinds of sources will be most useful, appropriate, relevant, and reliable. Keep in mind that you are unlikely to find all the sources you need online. Researchers must be equally skilled at locating sources in print and in electronic formats.

The types of sources that you will be expected to use will vary from discipline to discipline and assignment to assignment. The sources that are most appropriate will depend on your writing situation:

- the assignment,

- your purpose for writing,

- your audience, and

- the genre (or type).

(To learn more about the writing situation, see Chapter 5.)

For example, if you were writing an article for a local PTA newsletter (genre) to inform (purpose) parents (audience) about the school board’s decision to provide more nutritious lunches for children, you might interview the school’s nutritionist and gather data comparing the nutritional value of the typical new lunch (mini carrots, pita, hummus, and roasted chicken) to the nutritional value of the typical previous lunch (pizza, french fries, and Jell-o). You might also talk with the parents in the school district who were instrumental in getting the lunch menu improved and perhaps even ask some of the children their opinions regarding the new menu.

In contrast, if you were writing a research project (genre) for a history class (audience: your instructor) in which you argued (purpose) that skilled military commanders enabled the South to prolong the American Civil War, you might consult diaries written by Union soldiers, scholarly books and journal articles on Civil War battles and strategy, and maps showing troop movements.

PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SOURCES

The examples above mention primary (or firsthand) sources, such as interviews and diary entries, as well as secondary sources, such as books and articles. Primary sources include the following:

- historical documents (letters, diaries, speeches),

- literary works, autobiographies,

- original research reports,

- eyewitness accounts, and

- your own interviews, observations, or correspondence.

For example, a report on a study of heart disease written by the researcher who conducted the study is a primary source, as is a novel by William Faulkner. In addition, what you say or write can be a primary source. Your own interview with a heart attack survivor for a paper on heart disease is a primary source.

Secondary sources, in contrast, report or comment on primary sources. A journal article that reviews several previously published research reports on heart disease is a secondary source. A book written about William Faulkner by a literary critic or biographer is a secondary source.

Depending on your topic, you may use primary sources, secondary sources, or both. For a research project comparing the speeches of Abraham Lincoln with those of Franklin D. Roosevelt, you would probably read and analyze the speeches and listen to recordings of Roosevelt delivering his speeches (primary sources). But to learn about Lincoln’s and Roosevelt’s domestic policies, you would probably rely on several histories or biographies (secondary sources).

SCHOLARLY, POPULAR, AND REFERENCE SOURCES

In addition to primary and secondary, sources can also be classified as scholarly, popular, or reference sources. Scholarly sources are written by professional academics and scientific researchers and include both books by university presses or professional publishing companies and articles in discipline-specific academic journals that are edited by experts in the field. (For more on using a database to narrow sources by type, see Chapter 23.) University presses include Oxford University Press, Princeton University Press, and the University of Nebraska Press (among many others).

There are thousands of highly regarded academic journals, ranging from Nature (a key journal in biology and the life sciences) to The Lancet (an important medical journal) to American Economic Review (a key journal for economists). Articles in academic journals often fall into two main categories.

- Reports on original research conducted by the writer.

- Surveys of previous research on a topic to identify key areas of agreement, which then become part of the accepted body of knowledge in the discipline.

Many scholarly sources are peer reviewed, which means the articles and books undergo a rigorous process of review by other scholars in the same discipline before they are accepted for publication. For these reasons, scholarly resources are accepted as accurate and reliable, and they usually form the basis of most research in academic papers.

Reference works are well-organized compendiums of facts, data, and information. They are intended to be consulted to answer specific questions rather than to be read from beginning to end. Dictionaries, encyclopedias, and thesauruses are common reference works.

Students and researchers frequently use discipline-specific reference works. For example, students of literature might consult Benet’s Reader’s Encylopedia or The Oxford Companion to English Literature. Like scholarly resources, reference works are checked closely for accuracy, which makes them reliable sources of information. Many reference works also include suggestions for further reading, which can help researchers in their quest for additional resources. While reference works are a handy place to look up background information, they are not appropriate sources on which to base a research project.

Popular sources (newspapers, magazines, and general-interest nonfiction books) typically discuss what is going on in the “real world.” For example, they publish stories about what happened and to whom — effects of a piece of legislation on a community, one woman’s story of overcoming adversity to become successful in college or business. The subject matter is treated in a way that makes it accessible to most readers. Difficult topics are explained simply. One type of popular source, known as a trade journal, is aimed at people in specific professions. Trade journals provide the latest information on new ideas, products, personnel, events, and trends in an industry.

“Popular” does not necessarily mean unreliable. For example, a newspaper like the Wall Street Journal and a magazine like Time are good sources of information. The articles they publish are written by journalists who are trained in methods of research. Some popular magazines such as Scientific American and the Economist are quite serious indeed. At the other end of the spectrum are mass-circulation magazines, like People and Sports Illustrated, that are concerned primarily with celebrities and showmanship. Sources at the “celebrity” end of the spectrum may be useful for finding examples, but these publications often have little or no academic credibility. (See “Evaluating Sources” for more on this topic.)

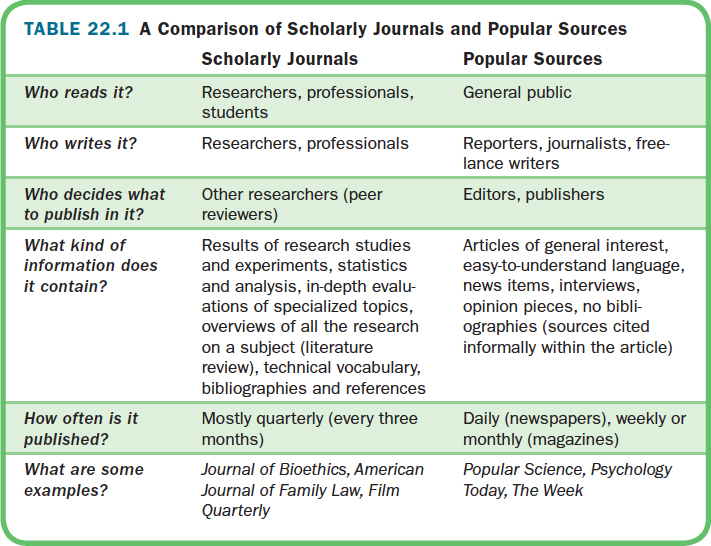

Table 22.1 summarizes some of the differences between scholarly and popular sources. For most college research projects, consulting and citing popular sources is acceptable, but no academic paper should rely solely on popular sources. Distinguishing among scholarly, popular, and reference sources when they are accessed through a database can be tricky, since visual cues, like the glossy paper and splashy photographs, that distinguish popular sources from scholarly ones are missing. Instead, you can use database tools or consult a reference librarian to help you determine source type.

BOOKS, ARTICLES, AND MEDIA SOURCES

A useful way to choose appropriate source types is to consider your needs in terms of the depth and type of content the source provides. Books often take years of study to produce and are often written by authorities on the subject, so they are likely to offer the most in-depth, comprehensive discussions of topics. Most scholarly books also provide pages and pages of research citations to help you dig further into any topic you find interesting or useful. Printed books provide an index to help you locate specific topics; e-books allow you to conduct keyword searches.

Articles are much briefer than books. In fact, most articles are under twenty pages, and some are as short as two or three pages. They tend to be more focused than books, exploring just one or two key points. They may also be more up-to-date, since they can be written and produced more rapidly than books can.

Most of the articles you access through your library’s databases begin with an abstract, or brief summary. Reading the abstract can help you determine whether the article will be useful to your research. Keyword searches in electronic articles can help you locate the topics you are researching, and many academic databases use keywords to link you to other articles that may be useful in your research. (For more on keyword searching, see Chapter 23.)

Media sources, such as photographs and information graphics, documentaries, audio podcasts, or works of fine art, can be useful for ideas and information. While in popular sources, media items may be used to illustrate a text simply to attract readers, in academic texts, media must play a more substantial role. Use images in printed texts, or video and sound files in online texts, to illustrate a concept or to provide an example, but do not include illustrations merely for window dressing. Finally, keep in mind that documentaries may include fictional elements. Evaluate media sources carefully before including them as sources.

As you seek answers to your research questions, you will likely need to consult various types of sources. Let’s suppose you are writing a research project about narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), a recognized psychological disorder in which a person is obsessively concerned with ideas of his or her own personal superiority, power, and prestige. Through the process of narrowing your topic, you have decided to focus your paper on the behaviors associated with the disorder. What types of sources might you use?

- To help your readers understand exactly what NPD is, you might look to a reference book, such as the DSM-V (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition), a key reference work in psychology. The DSM is published by the American Psychological Association, which makes it a reliable resource.

- To research the real-world behaviors of people with NPD, you might consult several types of books. Scholarly books written by psychologists and published by university presses might offer case studies of people with NPD. You will likely also find books written by people who have NPD, in which they talk about their experiences and feelings. By using both types of sources, you can explore two sides of the issue: not only the clinical, diagnostic side of NPD but also the human side of it.

- To get your audience interested in your topic, you might begin by talking about celebrity behaviors that may reveal NPD. If you can find videos of celebrity interviews in which the celebrity exhibits behaviors associated with NPD, you will have found a good, reliable source to cite.