DRAFTING YOUR RESEARCH PROJECT

When drafting your research project, keep the following guidelines in mind:

- Remember your audience. Academic audiences will expect you to take a serious, academic tone, and may expect you to use the third person (he, she, it). The third person is more impersonal, sounds less biased, and may lend credibility to your ideas. Although your instructor may know a great deal about your topic, he or she may want you to demonstrate that you understand key terms and concepts, so definitions and explanations may be required.

- Follow the introduction, body, and conclusion format, and for most research papers, place your thesis in the introduction. A straightforward organization, with your thesis in the introduction, is usually the best choice for a research paper, since it allows readers to see from the outset how your supporting reasons relate to your main point. However, for papers analyzing a problem or proposing a solution, placing your thesis near the end may be more effective. For example, if you were writing an essay proposing stricter traffic laws on campus, you might begin by documenting the problem — describing accidents that have occurred and detailing their frequency. You might conclude your essay by suggesting that your college lower the speed limit on campus and install two new stop signs.

- Follow your outline or graphic organizer, but feel free to make changes as you work. You may discover a better organization, think of new ideas about your topic, or realize that a subtopic belongs in a different section. Don’t feel compelled to follow your outline or organizer to the letter, but be sure to address the topics you list.

- Refer to your source notes frequently as you write. If you do so, you will be less likely to overlook an important piece of evidence. If you suspect that a note is inaccurate in some way, check the original source.

- State and support the main point of each paragraph. Use your sources to substantiate, explain, or provide detail to support your main points. Make clear for your readers how your paragraph’s main point supports your thesis as well as how the evidence you supply supports your paragraph’s main point. Support your major points with evidence from a variety of sources. Doing so will strengthen your position. Relying on only one or two sources may make readers think you did insufficient research. But remember that your paper should not be just a series of facts, quotations, and statistics taken from sources. The basis of the paper should be your ideas and thesis, not merely a summary of what others have written about the topic. (For more on writing effective supporting paragraphs for a research project, see below.)

- Use strong transitions. Because a research paper may be lengthy or complex, readers need strong transitions to guide them from paragraph to paragraph and section to section. Make sure your transitions help readers understand how you have divided the topic and how one point relates to another.

- Use source information in a way that does not mislead your readers. Although you are presenting only a portion of someone else’s ideas, make sure you are not using information in a way that is contrary to the writer’s original intentions.

- Include source material only for a specific purpose. Just because you discovered an interesting statistic or a fascinating quote, don’t feel that you must use it. Information that doesn’t support your thesis will distract your reader and weaken your paper. Images may add visual interest, but in most academic disciplines, illustrations should be used only when they serve a useful purpose (such as when they provide evidence or are the subject of your analysis, as for an art history project).

- Incorporate in-text citations for your sources as you draft. Whenever you paraphrase, summarize, or quote a source, be sure to include an in-text citation.

USING RESEARCH TO SUPPORT YOUR IDEAS

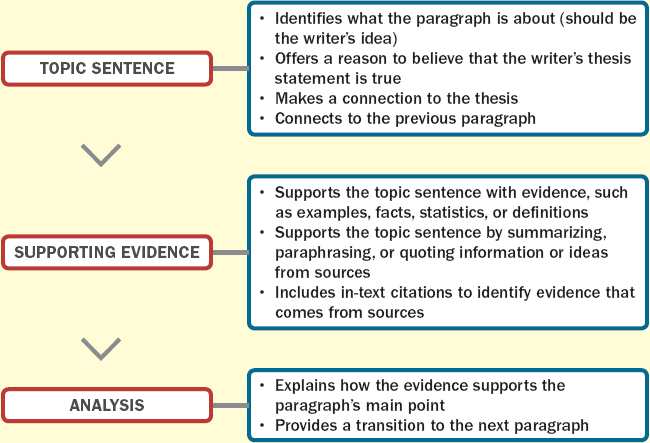

Supporting paragraphs in research projects have three parts, as shown in Figure 24.2.

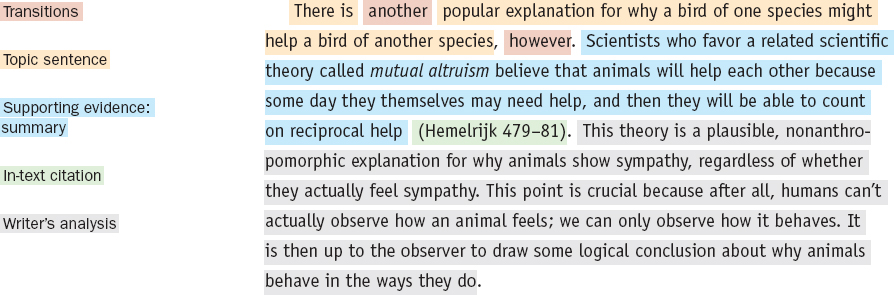

Each of these three parts is crucial: Without a topic sentence, readers are left to wonder what the main point is. Without the evidence, readers are left to wonder whether the main point is supported. Without the analysis, readers are left to make sense of the evidence and figure out how the evidence supports the topic on their own. Of course, writers must also connect the parts within the paragraph and connect the paragraph to the rest of the essay. The paragraph in Figure 24.3 shows this three-part structure at work. (It was taken from the sample MLA-style research project at the end of this chapter. For more on using transitions and repetition to make connections, see Chapter 8.)

USING IN-TEXT CITATIONS TO INTEGRATE SOURCE INFORMATION

When writing a research project, the goal is to support your own ideas with information from sources, integrating that information so that you achieve an easy-to-read flow. Along with transitions and strategic repetition, in-text citations (brief references in the body of your paper) make this seamless flow possible. These in-text citations direct readers to the list of works cited (or references) at the end of the research project, where they can find all the information they need to locate the sources for themselves. When used effectively, in-text citations also mark where the writer’s ideas end and information from sources begins.

Many academic disciplines have a preferred format, or style, for in-text citations and lists of works cited (or references). In English and the humanities, the preferred documentation format is usually that of the Modern Language Association (MLA) and is known as MLA style. In the social sciences, the guidelines of the American Psychological Association (APA) are often used; these guidelines are called APA style. These are the two most widely used formats and are discussed in detail later in this chapter. A third popular style, which many scientists follow, was created by the Council of Science Editors (CSE); you can find a book detailing CSE style in your college library; citation managers, like RefWorks or EndNote, can also help you format citations in CSE style.

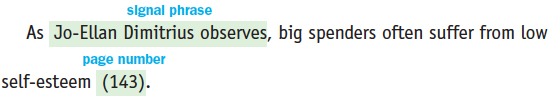

In MLA style, an in-text citation usually includes the author’s last name and the page number(s) on which the information appeared in the source. (Use just the author’s name for one-page sources and online sources, like Web pages, that do not have page numbers.) This information can be incorporated in two ways:

- In a signal, or attribution, phrase

- In a parenthetical citation

Using a signal phrase. When using a signal phrase, include the author’s name with an appropriate verb before the borrowed material, and put the page number(s) in parentheses at the end of the sentence:

Using a signal phrase before and a page number after borrowed material also helps readers clearly distinguish your ideas from those of your sources. Notice how the writer in Figure 24.3 uses in-text citations to make this clear.

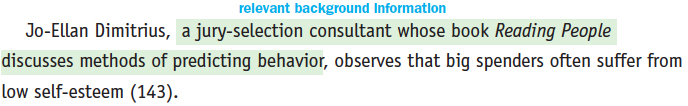

Often, providing some background information about the author the first time you mention a source is useful to readers, especially if the author is not widely known:

Such information helps readers understand that the source is relevant and credible.

Using a signal phrase will help you integrate information from sources smoothly into your paper. Most summaries and paraphrases and all quotations need such an introduction. Compare the paragraphs below.

QUOTATION NOT INTEGRATED

Anecdotes indicate that animals experience emotions, but anecdotes are not considered scientifically valid. “Experimental evidence is given almost exclusive credibility over personal experience to a degree that seems almost religious” (Masson and McCarthy 3).

QUOTATION INTEGRATED

Anecdotes indicate that animals experience emotions, but anecdotes are not considered scientifically valid. Masson and McCarthy, who have done extensive field observation, comment, “Experimental evidence is given almost exclusive credibility over personal experience to a degree that seems almost religious” (3).

In the first example paragraph, the quotation is merely dropped in. In the second, the signal phrase, including background of the source authors, smooths the connection.

When writing signal phrases, vary the verbs you use and where you place the signal phrase. The following verbs are useful for introducing many kinds of source material:

| advocates | contends | insists | proposes |

| argues | demonstrates | maintains | shows |

| asserts | denies | mentions | speculates |

| believes | emphasizes | notes | states |

| claims | explains | points out | suggests |

In most cases, a neutral verb such as states, explains, or maintains will be most appropriate. Sometimes, however, a verb such as denies or speculates may more accurately reflect the source author’s attitude.

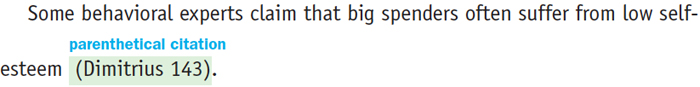

Using a parenthetical citation. When you are merely citing facts or have already identified a source author, a parenthetical citation that includes the author’s last name and the page number may be sufficient:

INTEGRATING QUOTATIONS INTO YOUR RESEARCH PROJECT

Although quotations can lend interest to your paper and provide support for your ideas, they must be used appropriately. The following sections answer some common questions about the use of quotations. The in-text citations follow MLA style. (See p. 639 for creating in-text citations in APA style.)

Using quotations. Do not use quotations to reveal ordinary facts and opinions. Look carefully at what you intend to quote. Quote only when

- The author’s wording is unusual, noteworthy, or striking. The quotation “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere” from Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” is probably more effective than any paraphrase.

- The original words express the exact point you want to make and a paraphrase might alter or distort the statement’s meaning.

- The statement is a strong, opinionated, exaggerated, or disputed idea that you want to make clear is not your own.

Formatting long quotations. In MLA style, lengthy quotations (more than three lines of poetry or more than four typed lines of prose) are indented in a block, one inch from the left margin. In APA style, quotations of more than forty words are indented as a block half an inch from the left margin. In both styles, quotation marks are omitted, and quotations are double spaced.

Like a shorter quotation in the main text, a block quotation should always be introduced by a signal phrase. Use a colon at the end of the signal phrase if it is a complete sentence, as in the following example:

In her book Through a Window, which elaborates on her thirty years of experience studying and living among the chimps in Gombe, Tanzania, Jane Goodall gives the following account of Flint’s experience with grief:

Flint became increasingly lethargic, refused most food and, with his immune system thus weakened, fell sick. The last time I saw him alive, he was hollow-eyed, gaunt and utterly depressed, huddled in the vegetation close to where Flo had died. . . . The last short journey he made, pausing to rest every few feet, was to the very place where Flo’s body had lain. There he stayed for several hours, sometimes staring and staring into the water. He struggled on a little further, then curled up — and never moved again. (196–97)

Unlike a shorter quotation in the main text, the page numbers in parentheses appear after the final sentence period. (For a short quotation within the text, the page numbers within parentheses precede the period.)

Punctuating quotations. There are specific rules and conventions for punctuating quotations. The most important rules are listed below.

- Use single quotation marks to enclose a quotation within a quotation.

Coleman and Cressey argue that “concern for the ‘decaying family’ is nothing new” (147).

- Use a comma after a verb that introduces a quotation. Begin the first word of the quotation with a capital letter (enclosed in brackets if it is not capitalized in the source).

As Thompson and Hickey report, “There are three major kinds of ‘taste cultures’ in complex industrial societies: high culture, folk culture, and popular culture” (76).

- When a quotation is not introduced by a verb, it is not necessary to use a comma or capitalize the first word.

Buck reports that “pets play a significant part in both physical and psychological therapy” (4).

- Use a colon to introduce a quotation preceded by a complete sentence.

The definition is clear: “Countercultures reject the conventional wisdom and standards of the dominant culture and provide alternatives to mainstream culture” (Thompson and Hickey 76).

- For a paraphrase or quotation integrated into the text, punctuation follows the parenthetical citation; for a block quotation, the punctuation precedes the parenthetical citation.

Scientists who favor a related scientific theory called mutual altruism believe that animals help each other because when they themselves need help, they would like to be able to count on reciprocal assistance (Hemelrijk 479–81).

Franklin observed the following scene:

Her unhappy spouse moved around her incessantly, his attention and tender cares redoubled. . . . At length his companion breathed her last; from that moment he pined away, and died in the course of a few weeks. (qtd. in Barber 116)

- Place periods and commas inside quotation marks.

“The most valuable old cars,” notes antique car collector Michael Patterson, “are the rarest ones.”

- Place colons and semicolons outside quotation marks.

“Petting a dog increases mobility of a limb or hand”; petting a dog, then, can be a form of physical therapy (Buck 4).

- Place question marks and exclamation points inside quotation marks when they are part of the original quotation. No period is needed if the quotation ends the sentence.

The instructor asked, “Does the text’s description of alternative lifestyles agree with your experience?”

- Place question marks and exclamation points that belong to your own sentence outside quotation marks.

Is the following definition accurate: “Sociolinguistics is the study of the relationship between language and society”?

macmillanhighered.com/successfulwriting

macmillanhighered.com/successfulwriting

LearningCurve > Working with Sources (MLA); Working with Sources (APA)

Adapting quotations. Use the following guidelines when adapting quotations to fit in your own sentences.

- You must copy the spelling, punctuation, and capitalization exactly as they appear in the original source, even if they are in error. (See item 5 on p. 612 for the only exception.) If a source contains an error, copy it with the error and add the word sic (Latin for “thus”) in brackets immediately following the error.

According to Bernstein, “The family has undergone rapid decentralization since Word [sic] War II” (39).

- You can emphasize words in a quotation by underlining or italicizing them. However, you must add the notation emphasis added in parentheses at the end of the sentence to indicate the change.

“In unprecedented and increasing numbers, patients are consulting practitioners of every type of complementary medicine” (emphasis added) (Buckman and Sabbagh 73).

- You can omit part of a quotation, but you must add an ellipsis — three spaced periods (. . .) — to indicate that material has been deleted. You may delete words, sentences, paragraphs, or entire pages as long as you do not distort the author’s meaning by doing so.

According to Buckman and Sabbagh, “Acupuncture . . . has been rigorously tested and proven to be effective and valid” (188).

When an omission falls at the end of a quoted sentence, use the three spaced periods after the sentence period.

Thompson maintains that “marketers need to establish ethical standards for personal selling. . . . They must stress fairness and honesty in dealing with customers” (298).

If you are quoting only a word or phrase from a source, do not use an ellipsis before or after it because it will be obvious that you have omitted part of the original sentence. If you omit the beginning of a quoted sentence, you need not use an ellipsis unless what you are quoting begins with a capitalized word and appears to be a complete sentence.

- You can add words or phrases in brackets to make a quotation clearer or to make it fit grammatically into your sentence. Be sure that in doing so you do not change the original sense.

Masson and McCarthy note that the well-known animal researcher Jane Goodall finds that “the scientific reluctance to accept anecdotal evidence [of emotional experience is] a serious problem, one that colors all of science” (3).

- You can change the first word of a quotation to a capital or lowercase letter to fit into your sentence. If you change it, enclose it in brackets.

As Aaron Smith said, “The . . .” (32).

Aaron Smith said that “[t]he . . .” (32).

Research Project in Progress 7

Using your research notes, your revised thesis, and the organizational plan you developed for your research paper, write a first draft. Be sure to integrate sources carefully and to include in-text citations. (See MLA style guidelines or APA style guidelines for in-text citation models.)