The American Promise:

Printed Page 291

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 279

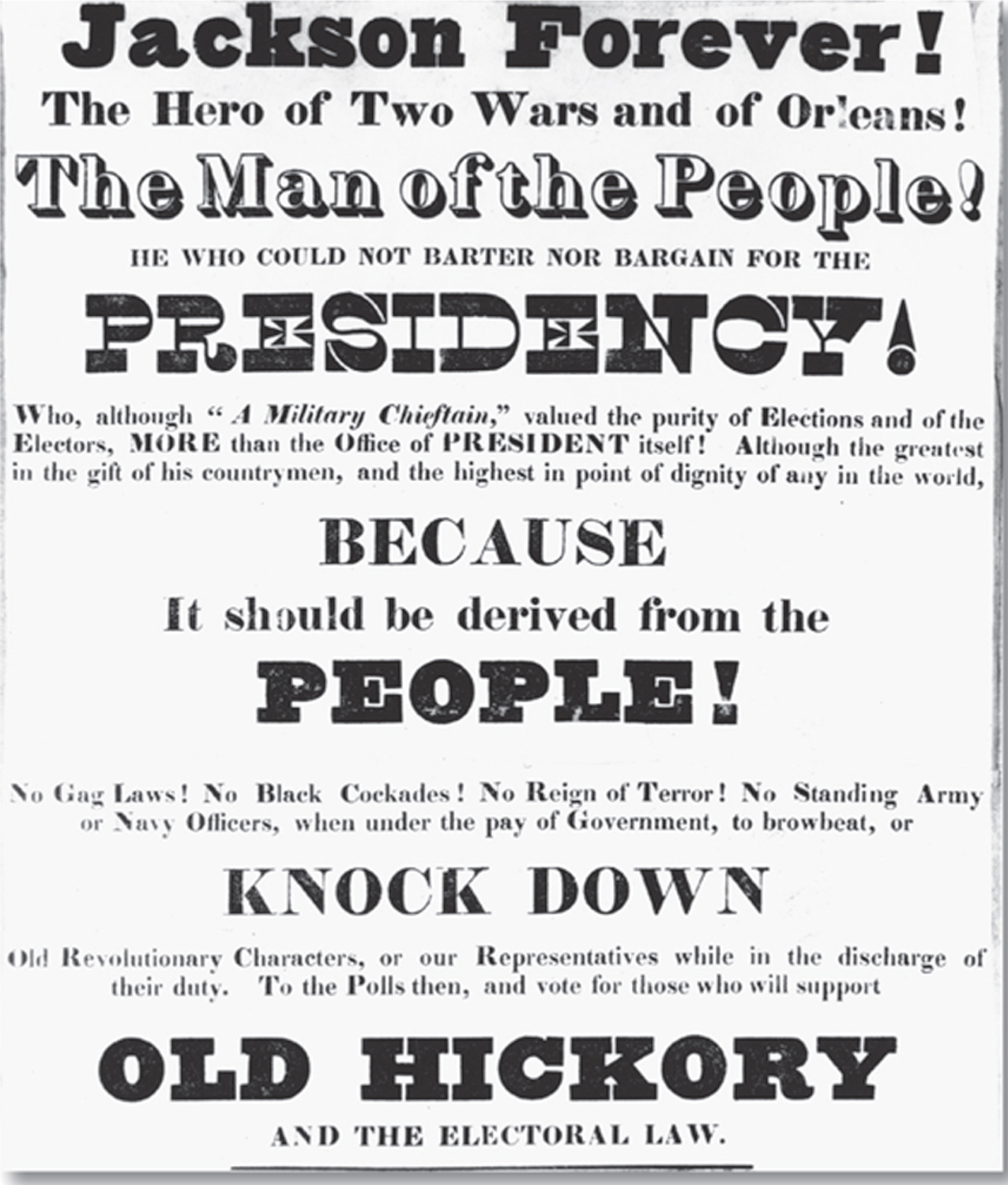

The Election of 1828 and the Character Issue

The campaign of 1828 was the first national election dominated by scandal and character questions. Claims about morality, honor, and discipline became central because voters used them to comprehend the kind of public official each man would make. Jackson and Adams presented two radically different styles of manhood.

John Quincy Adams was vilified by his opponents as an elitist, a bookish academic, and even a monarchist. They attacked his “corrupt bargain” of 1824—

Editors in favor of Adams played up Jackson’s violent temper, as evidenced by his participation in many duels, brawls, and canings. Jackson’s supporters used the same stories to project Old Hickory as a tough frontier hero who knew how to command obedience. As for learning, Jackson’s rough frontier education gave him a “natural sense,” wrote a Boston editor, that “can never be acquired by reading books—

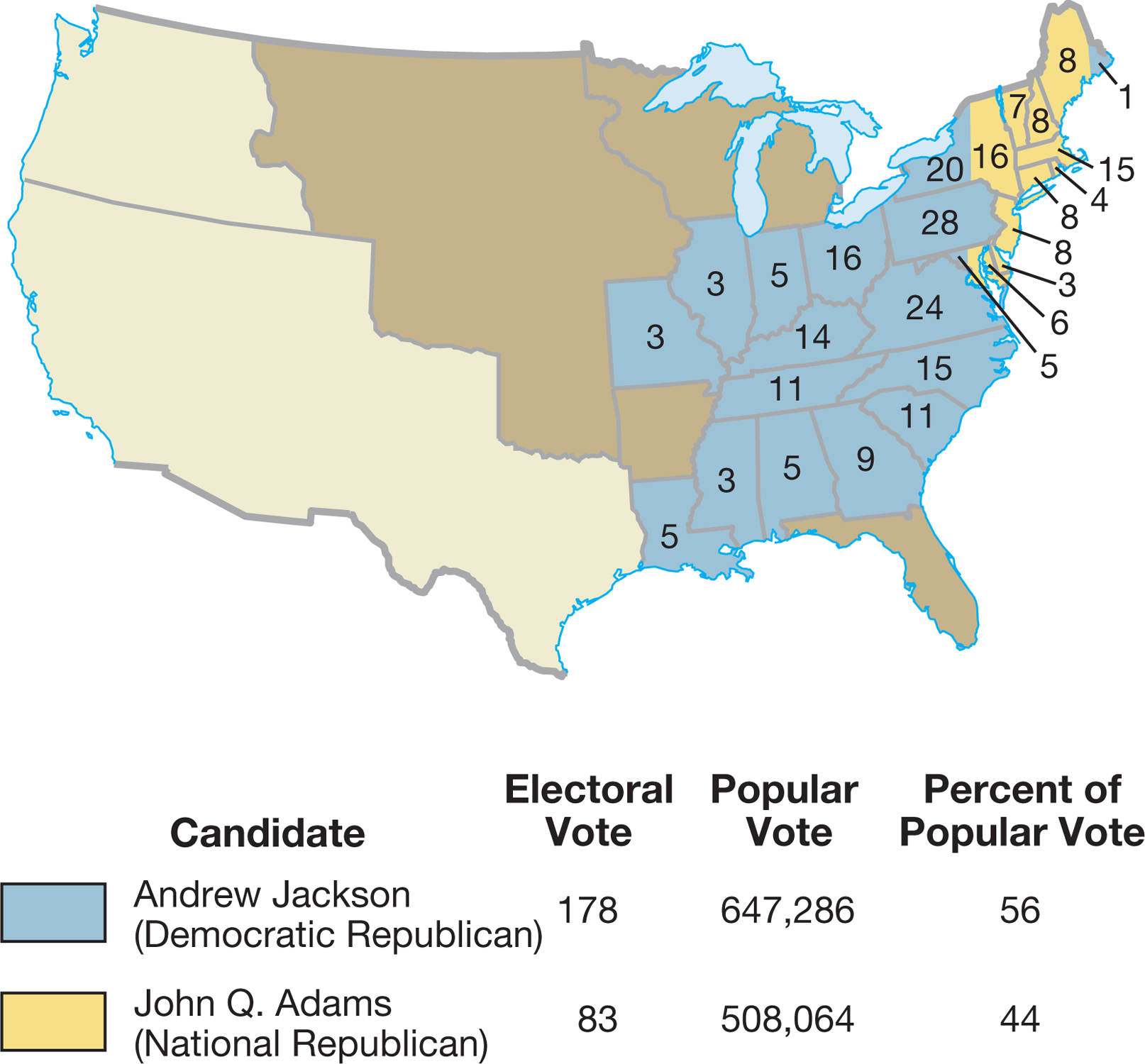

Jackson won a sweeping victory, with 56 percent of the popular vote and 178 electoral votes to Adams’s 83 (Map 11.2). Old Hickory took most of the South and West and carried Pennsylvania and New York as well; Adams carried the remainder of the East. Jackson’s vice president was John C. Calhoun, who had just served as vice president under Adams but had broken with Adams’s policies.

After 1828, national politicians no longer deplored the existence of political parties. They were coming to see that parties mobilized and delivered voters, sharpened candidates’ differences, and created party loyalty that surpassed loyalty to individual candidates and elections. Adams and Jackson clearly symbolized the competing ideas of the emerging parties: a moralistic, top-