The American Promise:

Printed Page 293

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 281

Indian Policy and the Trail of Tears

Probably nothing defined Jackson’s presidency more than his efforts to solve what he saw as the Indian problem. Thousands of Indians lived in the South and the old Northwest, and many remained in New England and New York. In his first message to Congress in 1829, Jackson, famed for his battles with the Creek and Seminole tribes in the 1810s, declared that removing the Indians to territory west of the Mississippi was the only way to save them. White civilization destroyed Indian resources and thus doomed the Indians, he claimed: “That this fate surely awaits them if they remain within the limits of the states does not admit of a doubt. Humanity and national honor demand that every effort should be made to avert so great a calamity.” Jackson never publicly wavered from this seemingly noble theme, returning to it in his next seven annual messages.

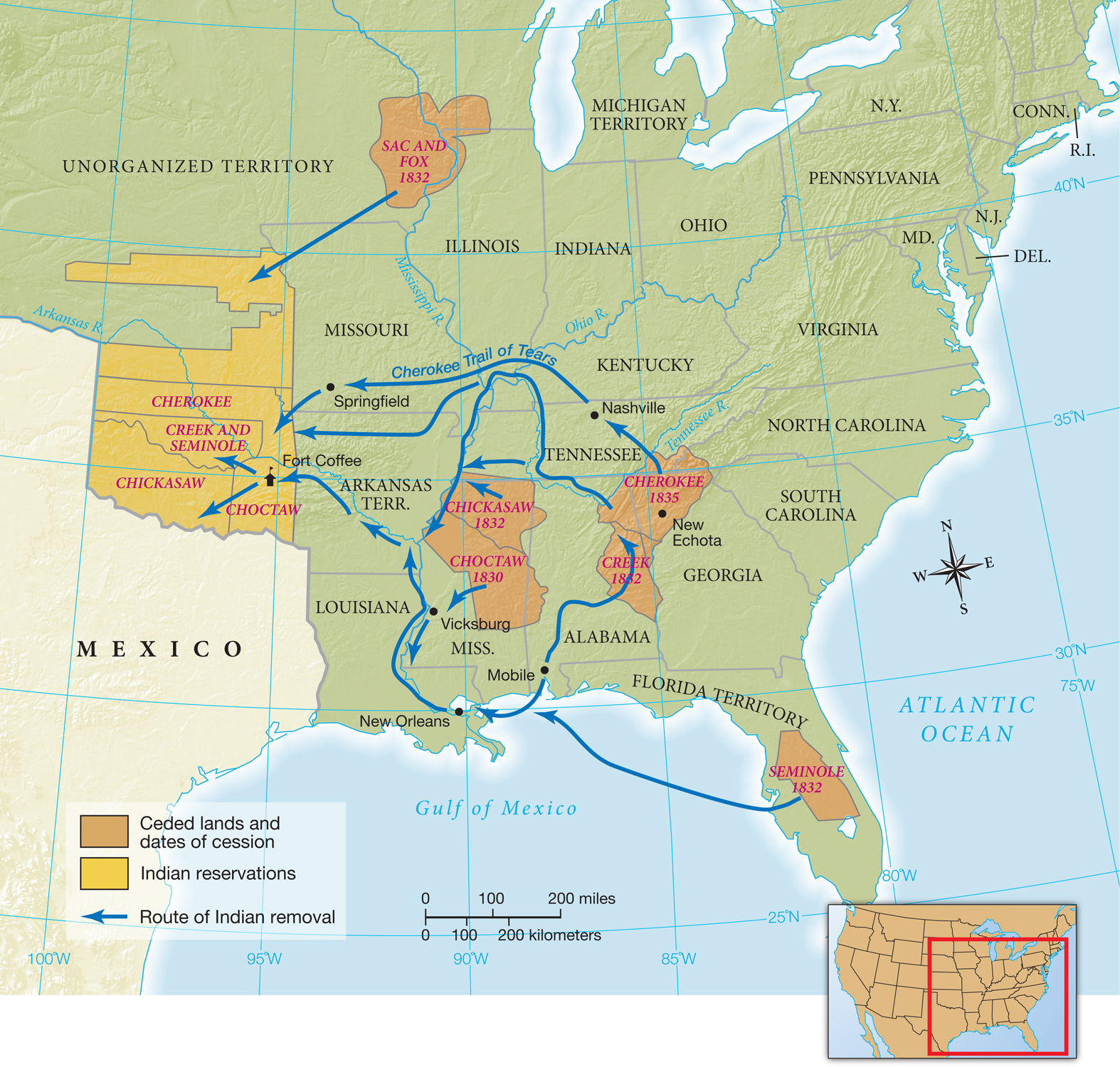

Prior administrations had experimented with different Indian policies. Starting in 1819, Congress funded missionary associations eager to “civilize” native peoples by converting them to Christianity and to whites’ agricultural practices. The federal government had also pursued aggressive treaty making with many tribes, dealing with the Indians as foreign nations (see “Creeks in the Southwest” in chapter 9 and “Osage and Comanche Indians” in chapter 10). In contrast, Jackson saw Indians as subjects of the United States (neither foreigners nor citizens) who needed to be relocated to assure their survival. Congress agreed and passed the Indian Removal Act of 1830. About 100 million acres of eastern land would be vacated for eventual white settlement under this act authorizing ethnic expulsion (Map 11.3).

The Indian Removal Act generated widespread controversy. Newspapers, public lecturers, and local clubs debated the expulsion law, and public opinion, especially in the North, was heated. “One would think that the guilt of African slavery was enough for the nation to bear, without the additional crime of injustice to the aborigines,” one writer declared in 1829. In an unprecedented move, thousands of northern white women signed antiremoval petitions. Between 1830 and 1832, women’s petitions rolled into Washington, arguing that sovereign peoples on the road to Christianity were entitled to stay on their land. Jackson ignored the petitions.

For many northern tribes, diminished by years of war, removal was already under way. But not all went quietly. In 1832 in western Illinois, Black Hawk, a leader of the Sauk and Fox Indians who had fought in alliance with Tecumseh in the War of 1812 (see “The War of 1812” in chapter 10), resisted removal. Volunteer militias attacked and chased the Indians into southern Wisconsin, where, after several skirmishes and a deadly battle (later called the Black Hawk War), Black Hawk was captured and some four hundred of his people were massacred.

The large southern tribes—

In 1831, when Georgia announced its plans to seize all Cherokee property, the tribal leadership took their case to the U.S. Supreme Court. In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the Court upheld the territorial sovereignty of the Cherokee people, recognizing their existence as “a distinct community, occupying its own territory, in which the laws of Georgia can have no force.” An angry President Jackson ignored the Court and pressed the Cherokee tribe to move west: “If they now refuse to accept the liberal terms offered, they can only be liable for whatever evils and difficulties may arise. I feel conscious of having done my duty to my red children.”

The Cherokee tribe remained in Georgia for two more years without significant violence. Then, in 1835, a small, unauthorized faction of the acculturated leaders signed a treaty selling all the tribal lands to the state, which rapidly resold the land to whites. Chief John Ross, backed by several thousand Cherokees, petitioned the U.S. Congress to ignore the bogus treaty to no avail. Most Cherokees refused to move, so in May 1838, the deadline for voluntary removal, federal troops arrived to remove them. Under armed guard, the Cherokees embarked on a 1,200-

In his farewell address to the nation in 1837, Jackson professed his belief in the humanitarian benefits of Indian removal: “This unhappy race . . .