The American Promise:

Printed Page 287

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 276

Chapter Chronology

Bankers and Lawyers

Entrepreneurs like the Lowell factory owners relied on innovations in the banking system to finance their ventures. Between 1814 and 1816, the number of state-chartered banks in the United States more than doubled from fewer than 90 to 208. By 1830, there were 330, and by 1840 hundreds more. Banks stimulated the economy by making loans to merchants and manufacturers and by enlarging the money supply. Borrowers were issued loans in the form of banknotes—certificates unique to each bank—that were used as money for all transactions. Neither federal nor state governments issued paper money, so banknotes issued by hundreds of individual banks became the country’s currency. Constant uncertainty about the true worth of a banknote injected extra risk into the economy. Additionally, the sheer variety of notes in circulation created ideal conditions for counterfeiters to get into the action.

Bankers exercised great power over the economy, deciding who would get loans and what the discount rates would be. The most powerful bankers sat on the board of directors for the second Bank of the United States, headquartered in Philadelphia and featuring eighteen branches throughout the country. The twenty-year charter of the first Bank of the United States had expired in 1811, and the second Bank of the United States opened for business in 1816 under another twenty-year charter. The rechartering of this bank would become a major issue in the 1832 presidential campaign.

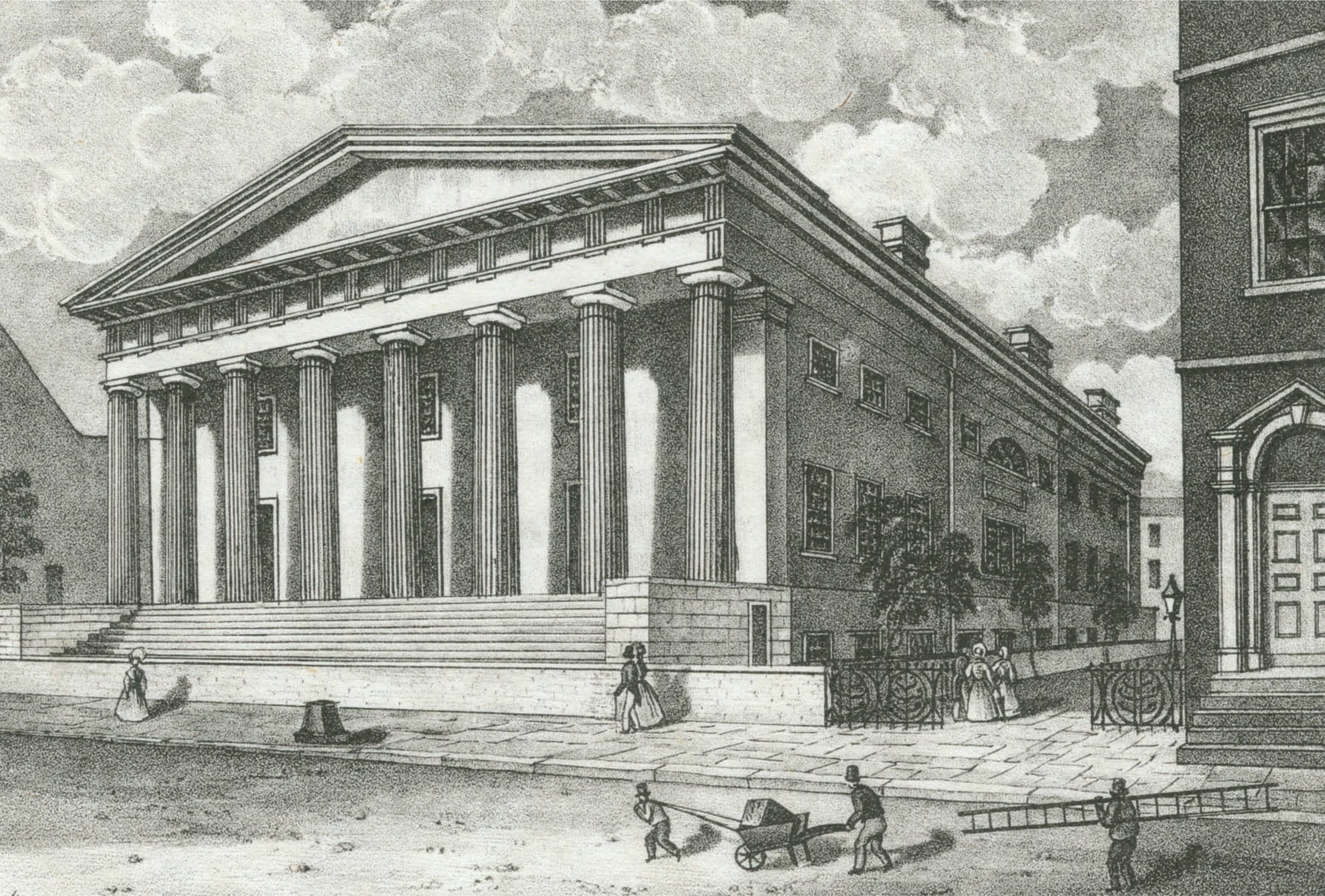

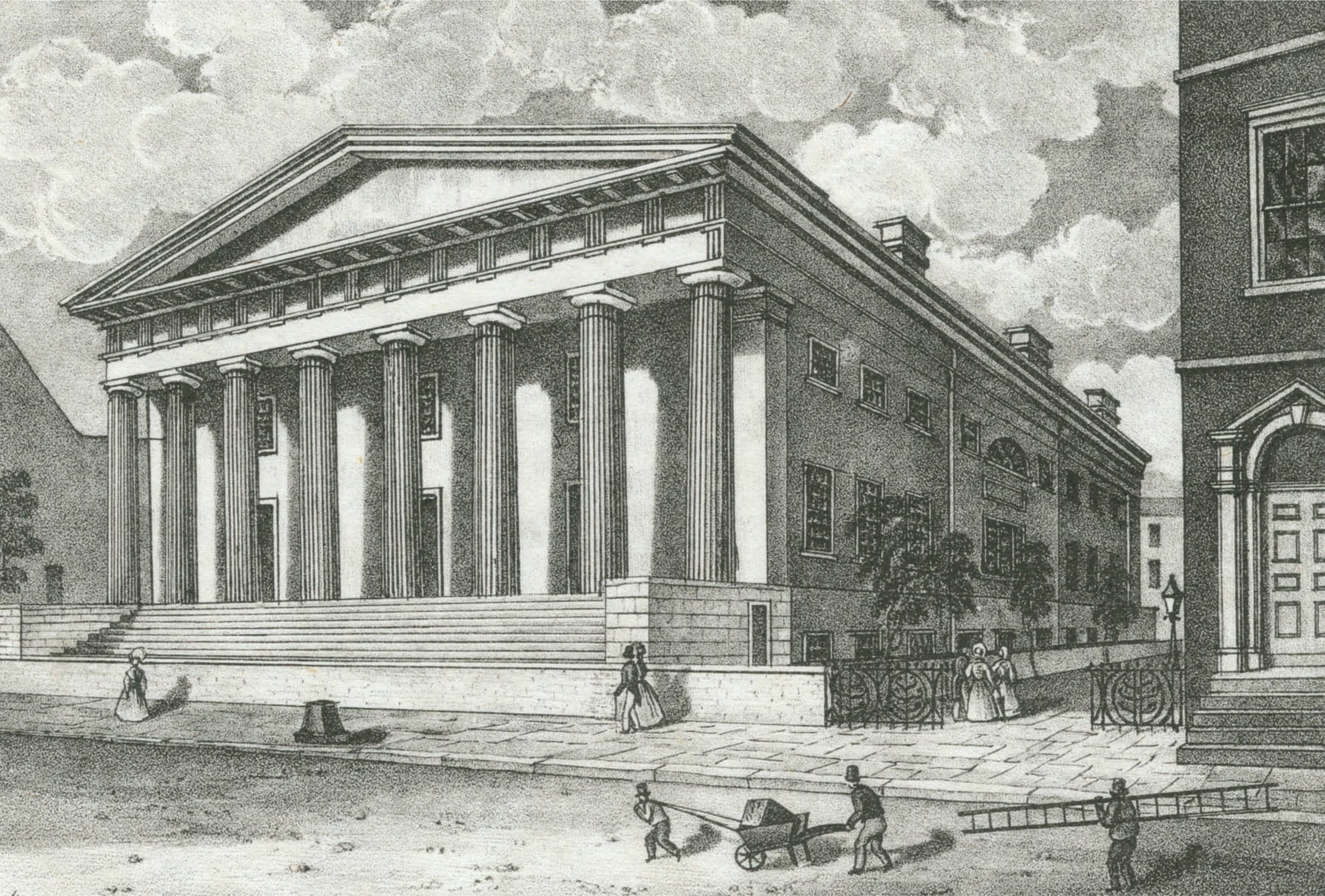

Second Bank of the United States, Philadelphia Along with the growth of state banks came a second federal Bank of the United States, chartered by Congress in 1816. It was headquartered in Philadelphia in this imposing Greek Revival building, constructed between 1818 and 1824. The architecture conveyed solidity, security, and timeless permanence. Despite appearances, the bank lost its charter during Andrew Jackson’s presidency and ceased to exist. Library Company of Philadelphia / The Bridgeman Art Library.

Lawyer-politicians too exercised economic power, by refashioning commercial law to enhance the prospects of private investment. In 1811, states started to rewrite their laws of incorporation (allowing the chartering of businesses by states), and the number of corporations expanded rapidly, from about twenty in 1800 to eighteen hundred by 1817. Incorporation protected individual investors from being held liable for corporate debts. State lawmakers also wrote laws of eminent domain, empowering states to buy land for roads and canals even from unwilling sellers. In such ways, entrepreneurial lawyers created the legal foundation for an economy that favored ambitious individuals interested in maximizing their own wealth.

Not everyone applauded these developments. Andrew Jackson, himself a skillful lawyer turned politician, spoke for a large and mistrustful segment of the population when he warned about the potential abuses of power “which the moneyed interest derives from a paper currency which they are able to control [and] from the multitude of corporations with exclusive privileges which they have succeeded in obtaining in the different states.” Jacksonians believed that ending government-granted privileges was the way to maximize individual liberty and economic opportunity.