The American Promise:

Printed Page 320

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 305

Chapter Chronology

Immigrants and the Free-Labor Ladder

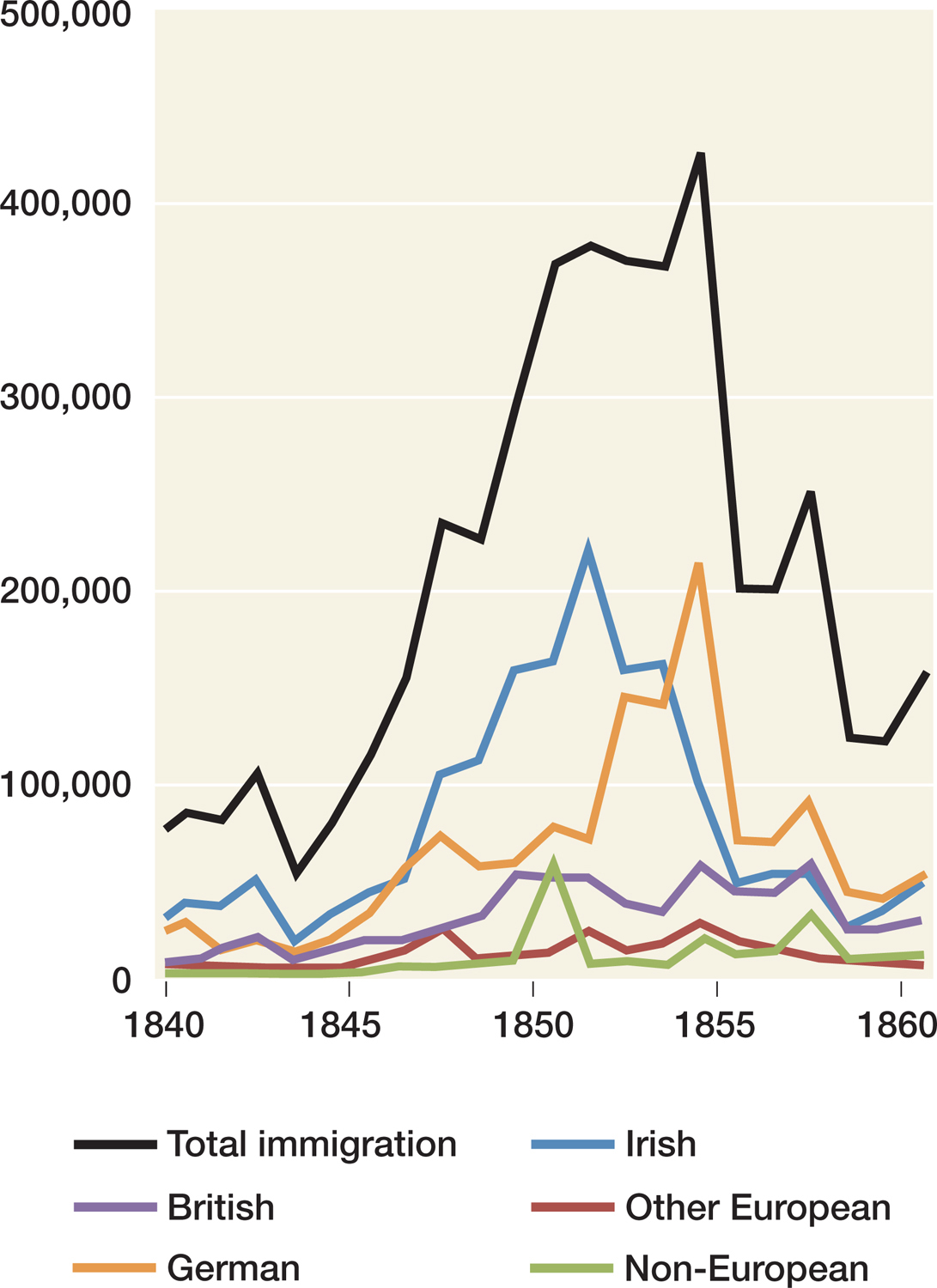

VISUAL ACTIVITY A German Immigrant in New York This 1855 painting depicts a German immigrant in New York City asking directions from an African American man cutting firewood. Like many other German immigrants, the man shown here appears relatively well off. Unlike most Irish immigrants, who arrived without family members, the German immigrant is accompanied by his daughter and son. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, purchased with funds from the State of North Carolina (52.9.2) READING THE IMAGE: How does the clothing of the German immigrant compare to that of the black man cutting wood and the white laborer on the right? What racial attitudes are illustrated by the painting? CONNECTIONS: How did mid-nineteenth century immigrants compare to native-born Americans?

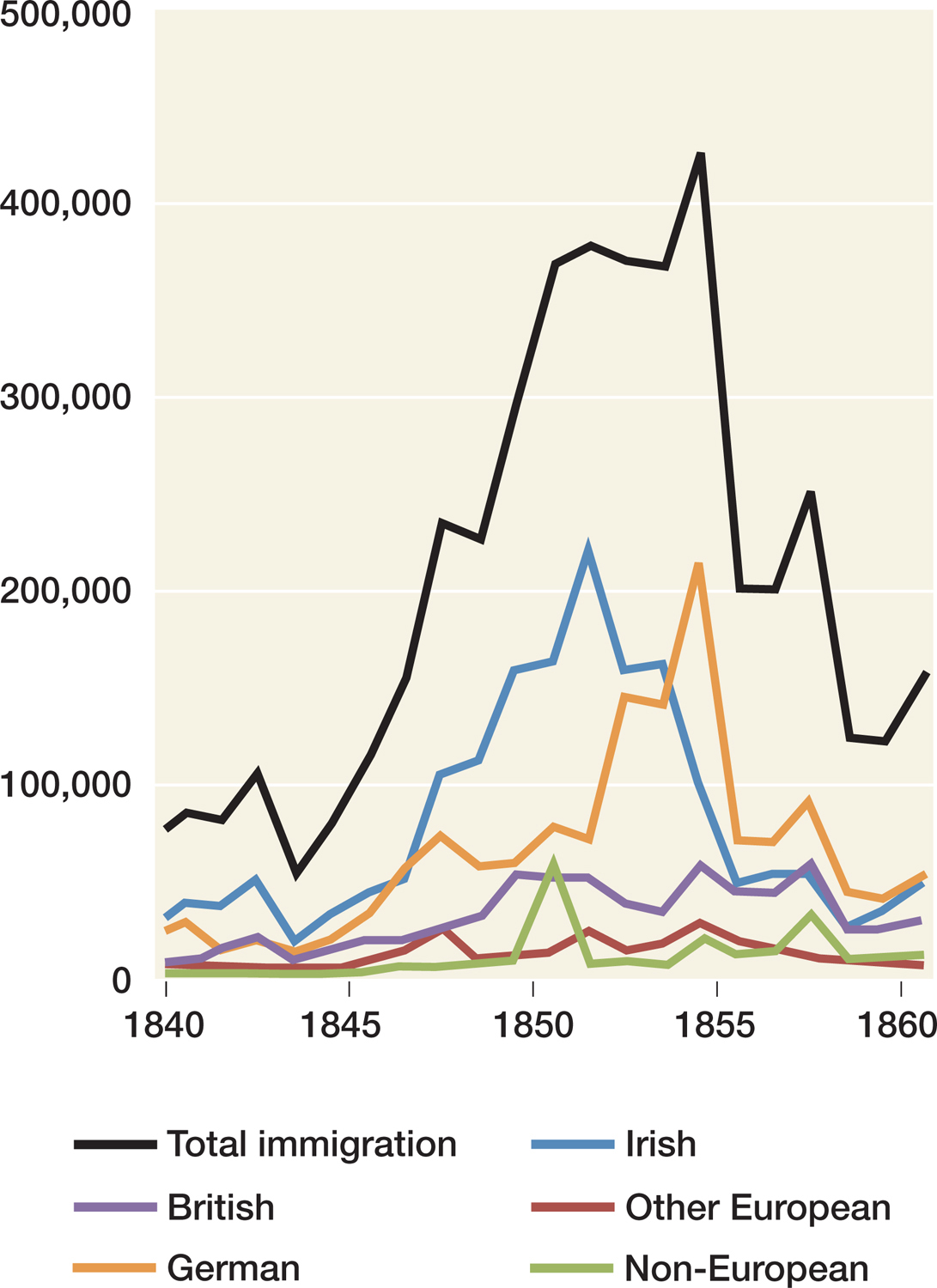

FIGURE 12.1 Antebellum Immigration, 1840–1860 Immigration shot up in the mid-1840s. Between 1848 and 1860, nearly 3.5 million immigrants entered the United States.

The risks and uncertainties of free labor did not deter millions of immigrants from entering the United States during the 1840s and 1850s. Almost 4.5 million immigrants arrived between 1840 and 1860, six times more than had come during the previous two decades (Figure 12.1).

Nearly three-fourths of the immigrants who arrived in the United States between 1840 and 1860 came from either Germany or Ireland. The majority of the 1.4 million Germans who entered during these years were skilled tradesmen and their families. Roughly a quarter were farmers, many of whom settled in Texas. German Americans were often Protestants and usually occupied the middle stratum of independent producers celebrated by free-labor spokesmen; relatively few worked as wage laborers or domestic servants.

Irish immigrants, in contrast, entered at the bottom of the free-labor ladder and struggled to climb up. Nearly 1.7 million Irish immigrants arrived between 1840 and 1860, nearly all of them desperately poor and often weakened by hunger and disease. Potato blight caused a catastrophic famine in Ireland in 1845 and returned repeatedly in subsequent years. Many Irish people crowded into ships and set out for America, where they congregated in northeastern cities. As one immigrant group declared, “All we want is to get out of Ireland; we must be better anywhere than here.”

Roughly three out of four Irish immigrants worked as laborers or domestic servants. Irish men dug canals, loaded ships, laid railroad track, and did odd jobs while Irish women worked in the homes of others—cooking, washing, ironing, minding children, and cleaning house. Almost all Irish immigrants were Catholic, which set them apart from the overwhelmingly Protestant native-born residents. Many natives regarded the Irish as hard-drinking, unruly, half-civilized folk. Job announcements commonly stated, “No Irish need apply.” One immigrant recalled that Irish laborers were thought of as “nothing . . . more than dogs . . . despised and kicked about.” Despite such prejudices, native residents hired Irish immigrants because they accepted low pay and worked hard.

In America’s labor-poor economy, Irish laborers could earn more in one day than in several weeks in Ireland. In America, one immigrant explained in 1853, there was “plenty of work and plenty of wages plenty to eat and no land lords thats enough what more does a man want.” But many immigrants also craved respect and decent working conditions.

Amidst the opportunities for some immigrants and native-born laborers, the free-labor system often did not live up to the optimistic vision outlined by Abraham Lincoln. Many wage laborers could not realistically aspire to become independent, self-sufficient property holders, despite the claims of free-labor proponents.

REVIEW How did the free-labor ideal account for economic inequality?