The American Promise:

Printed Page 327

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 310

Chapter Chronology

The Mexican Borderlands

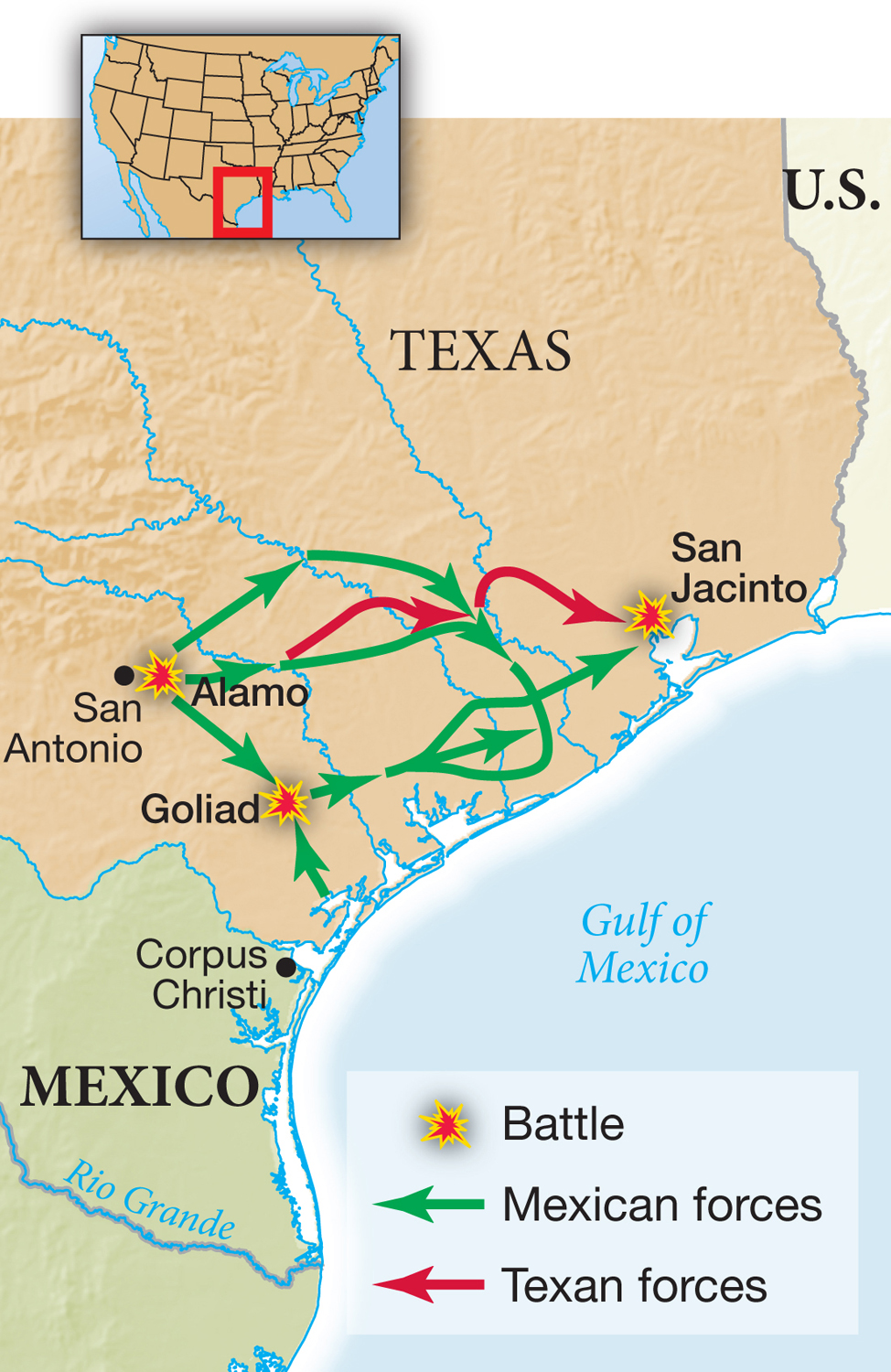

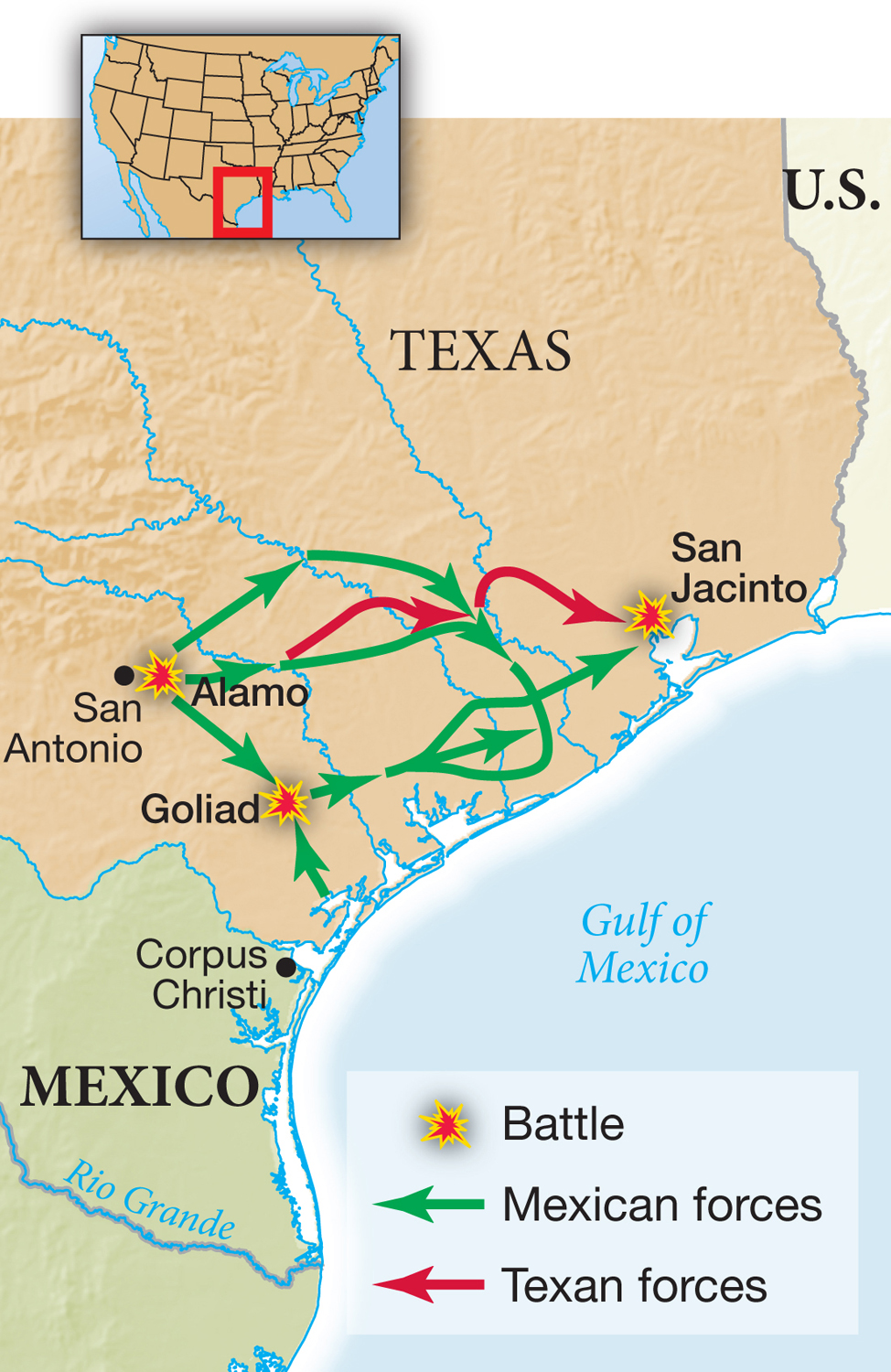

MAP 12.3 Texas and Mexico in the 1830s As Americans spilled into lightly populated and loosely governed northern Mexico, Texas and then other Mexican provinces became contested territory.

In the Mexican Southwest, westward-moving Anglo-American pioneers confronted northern-moving Spanish-speaking frontiersmen. On this frontier as elsewhere, national cultures, interests, and aspirations collided. Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821 (Map 12.3), but the young nation was plagued by civil wars, economic crises, quarrels with the Roman Catholic Church, and devastating raids by the Comanche, Apache, and Kiowa. Mexico found it increasingly difficult to defend its sparsely populated northern provinces, especially when faced with a neighbor convinced of its superiority and bent on territorial acquisition.

The American assault began quietly. In the 1820s, Anglo-American traders drifted into Santa Fe, a remote outpost in the northern province of New Mexico. The traders made the long trek southwest along the Santa Fe Trail (see Map 12.2) with wagons crammed with inexpensive American manufactured goods and returned home with Mexican silver, furs, and mules.

The Mexican province of Texas attracted a flood of Americans who had settlement, not long-distance trade, on their minds (see Map 12.3). Wanting to populate and develop its northern territory, the Mexican government granted the American Stephen F. Austin a huge tract of land along the Brazos River. In the 1820s, Austin offered land at only ten cents an acre, and thousands of Americans poured across the border. Most were Southerners who brought cotton and slaves with them.

By the 1830s, the settlers had established a thriving plantation economy in Texas. Americans numbered 35,000, while the Tejano (Spanish-speaking) population was less than 8,000. Few Anglo-American settlers were Roman Catholic, spoke Spanish, or cared about assimilating into Mexican culture. Afraid of losing Texas to the new arrivals, the Mexican government in 1830 banned further immigration to Texas from the United States and outlawed the introduction of additional slaves. The Anglo-Americans made it clear that they wanted to be rid of the “despotism of the sword and the priesthood” and to govern themselves.

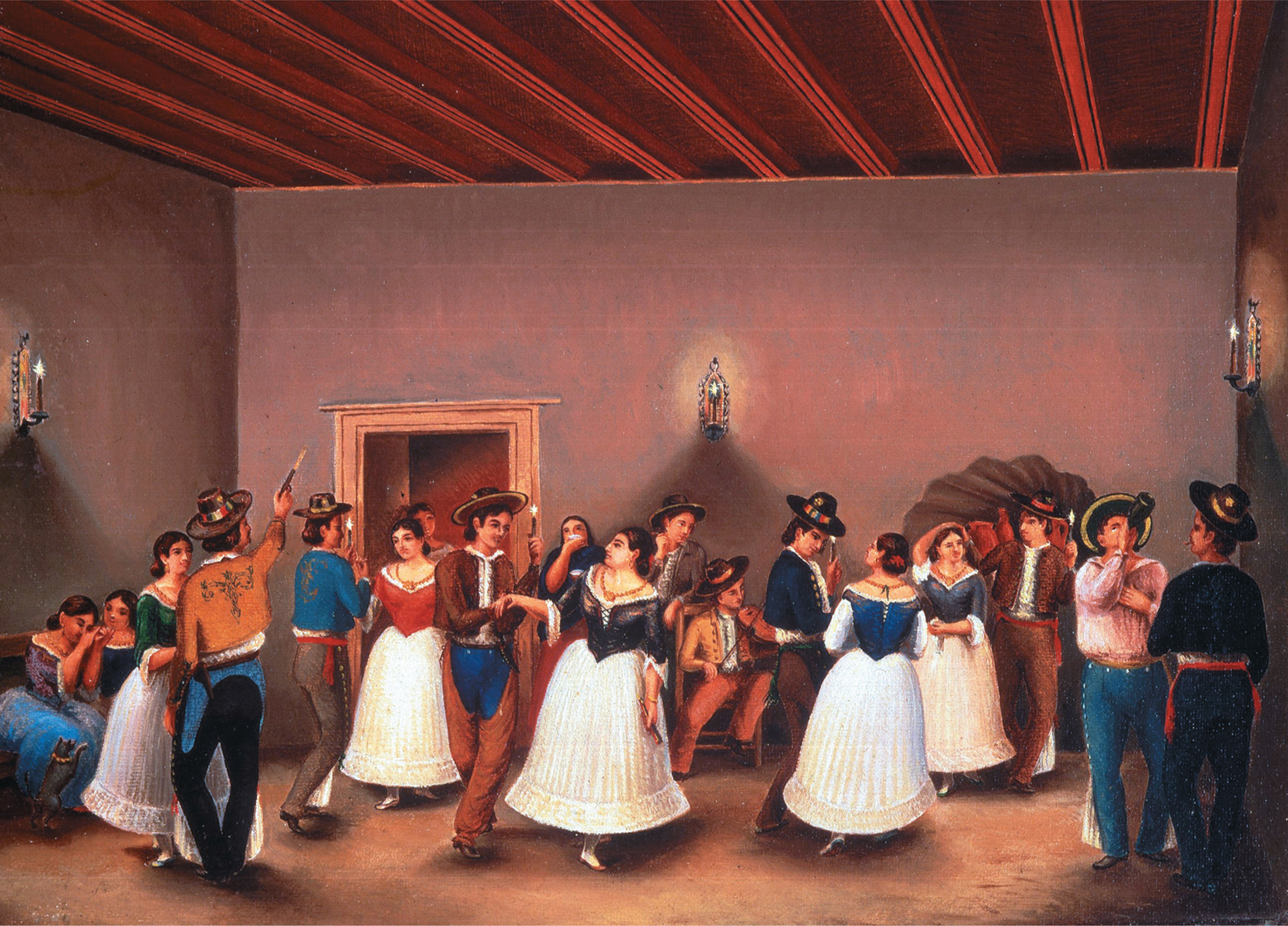

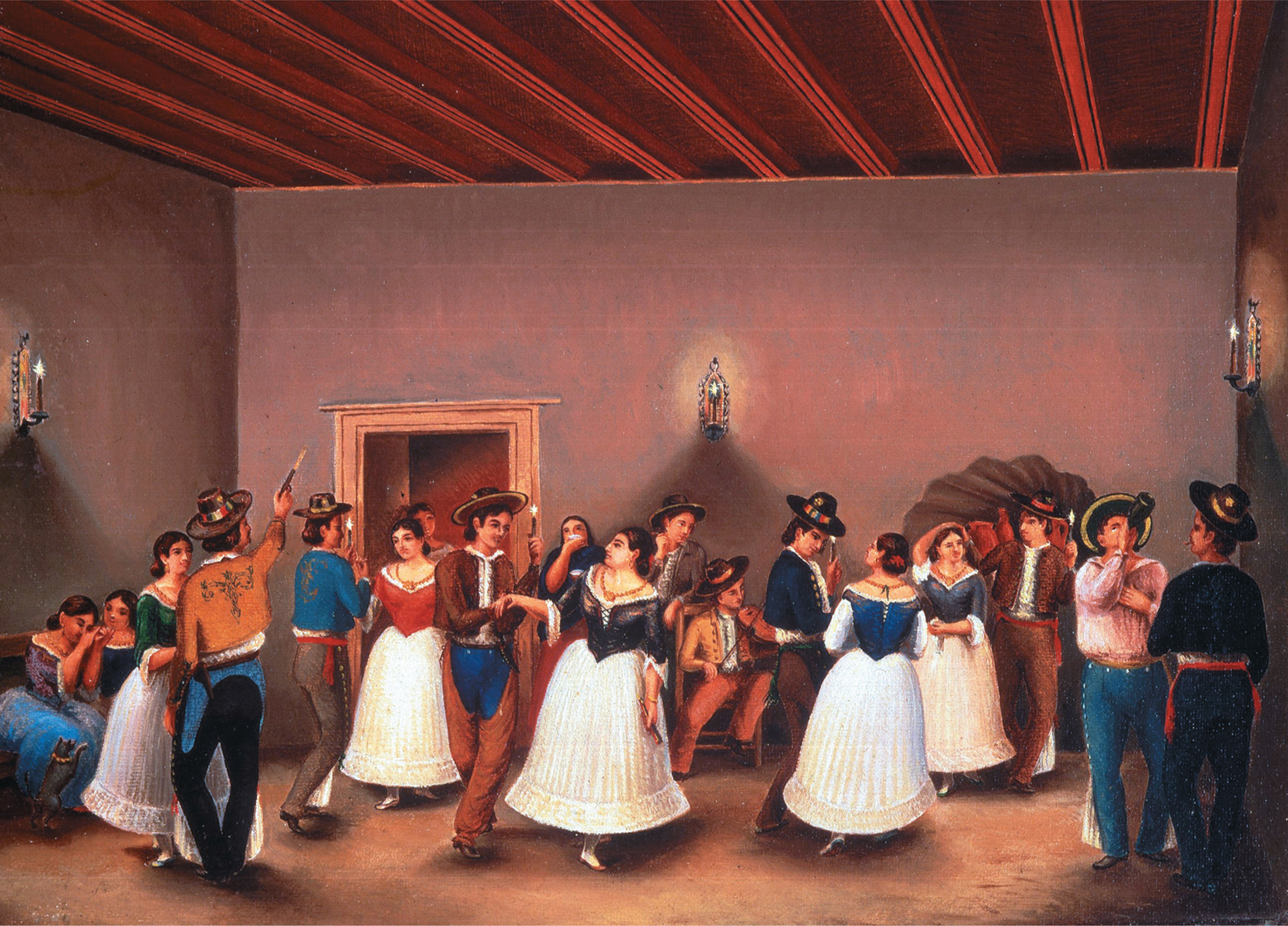

Fandango, by Theodore Gentilz, 1844 A small and resourceful Tejano community managed to develop a ranching economy in the harsh frontier conditions of Texas. The largest Hispanic population concentrated in San Antonio, where settlers reproduced as best they could the cultural traditions they carried with them. Here, well-dressed men and women perform a Spanish dance called the fandango. Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library at the Alamo.

When the Texan settlers rebelled, General Antonio López de Santa Anna ordered the Mexican army northward. In February 1836, the army arrived at the outskirts of San Antonio. Commanded by Colonel William B. Travis from Alabama, the rebels included the Tennessee frontiersman Davy Crockett and the Louisiana adventurer James Bowie, as well as a handful of Tejanos. They took refuge in a former Franciscan mission known as the Alamo. Santa Anna sent wave after wave of his 2,000-man army crashing against the walls until the attackers finally broke through and killed all 187 rebels. A few weeks later, outside the small town of Goliad, Mexican forces captured and executed almost 400 Texans as “pirates and outlaws.” In April 1836, at San Jacinto, General Sam Houston’s army adopted the massacre of Goliad as a battle cry and crushed Santa Anna’s troops in a surprise attack. The Texans had succeeded in establishing the Lone Star Republic, and the following year the United States recognized the independence of Texas from Mexico.

Texas War for Independence, 1836

Earlier, in 1824, in an effort to increase Mexican migration to the province of California, the Mexican government granted ranchos—huge estates devoted to cattle raising—to new settlers. Rancheros ruled over near-feudal empires worked by Indians whose condition sometimes approached that of slaves. In 1834, rancheros persuaded the Mexican government to confiscate the Franciscan missions and make their vast lands available to new settlement, a development that accelerated the decline of the California Indians. Devastated by disease, the Indians, who had numbered approximately 300,000 when the Spanish arrived in 1769, had declined to half that number by 1846.

Despite the efforts of the Mexican government, California in 1840 had a population of only 7,000 Mexican settlers. Non-Mexican settlers numbered only 380, but among them were Americans who championed manifest destiny. They sought to convince American emigrants who were traveling the Oregon Trail to head southwest on the California Trail (see Map 12.2). As a New York newspaper observed in 1845, “Let the tide of emigration flow toward California and the American population will soon be sufficiently numerous to play the Texas game.” Few Americans in California wanted a war, but many dreamed of living again under the U.S. flag.

In 1846, American settlers in the Sacramento Valley took matters into their own hands. Prodded by John C. Frémont, a former army captain and explorer who had arrived with a party of sixty buckskin-clad frontiersmen spoiling for a fight, the Californians raised an independence movement known as the Bear Flag Revolt. By then, James K. Polk, a champion of aggressive expansion, sat in the White House.

REVIEW Why did westward migration expand dramatically in the mid-nineteenth century?