The American Promise:

Printed Page 313

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 300

Chapter Chronology

Agriculture and Land Policy

The foundation of the United States’ economic growth lay in agriculture. A French traveler in the United States noted that Americans had “a general feeling of hatred against trees.” Although the traveler exaggerated, trees limited agricultural productivity because farmers had to spend much time and energy clearing trees to make fields suitable for cultivation. As farmers pushed westward in a quest for cheap land, they encountered the Midwest’s comparatively treeless prairie, where they could spend less time clearing land and more time with a plow and hoe. Rich prairie soils yielded bumper crops, enticing farmers to migrate to the Midwest by the tens of thousands between 1830 and 1860. The populations of Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Iowa exploded tenfold between 1830 and 1860, ten times faster than the growth of the nation as a whole.

Labor-saving improvements in farm implements also boosted agricultural productivity. Inventors tinkered to craft stronger, more efficient plows. In 1837, John Deere made a strong, smooth steel plow that sliced through prairie soil so cleanly that farmers called it the “singing plow.” Deere’s company produced more than ten thousand plows a year by the late 1850s. Human and animal muscles provided the energy for plowing, but Deere’s plows permitted farmers to break more ground and plant more crops.

Improvements in wheat harvesting also increased farmers’ productivity. In 1850, most farmers harvested wheat by hand, cutting two or three acres a day. In the 1840s, Cyrus McCormick and others experimented with designs for mechanical reapers, and by the 1850s a McCormick reaper that cost between $100 and $150 allowed a farmer to harvest twelve acres a day. Improved reapers and plows, usually powered by horses or oxen, allowed farmers to cultivate more land, doubling the corn and wheat harvests between 1840 and 1860.

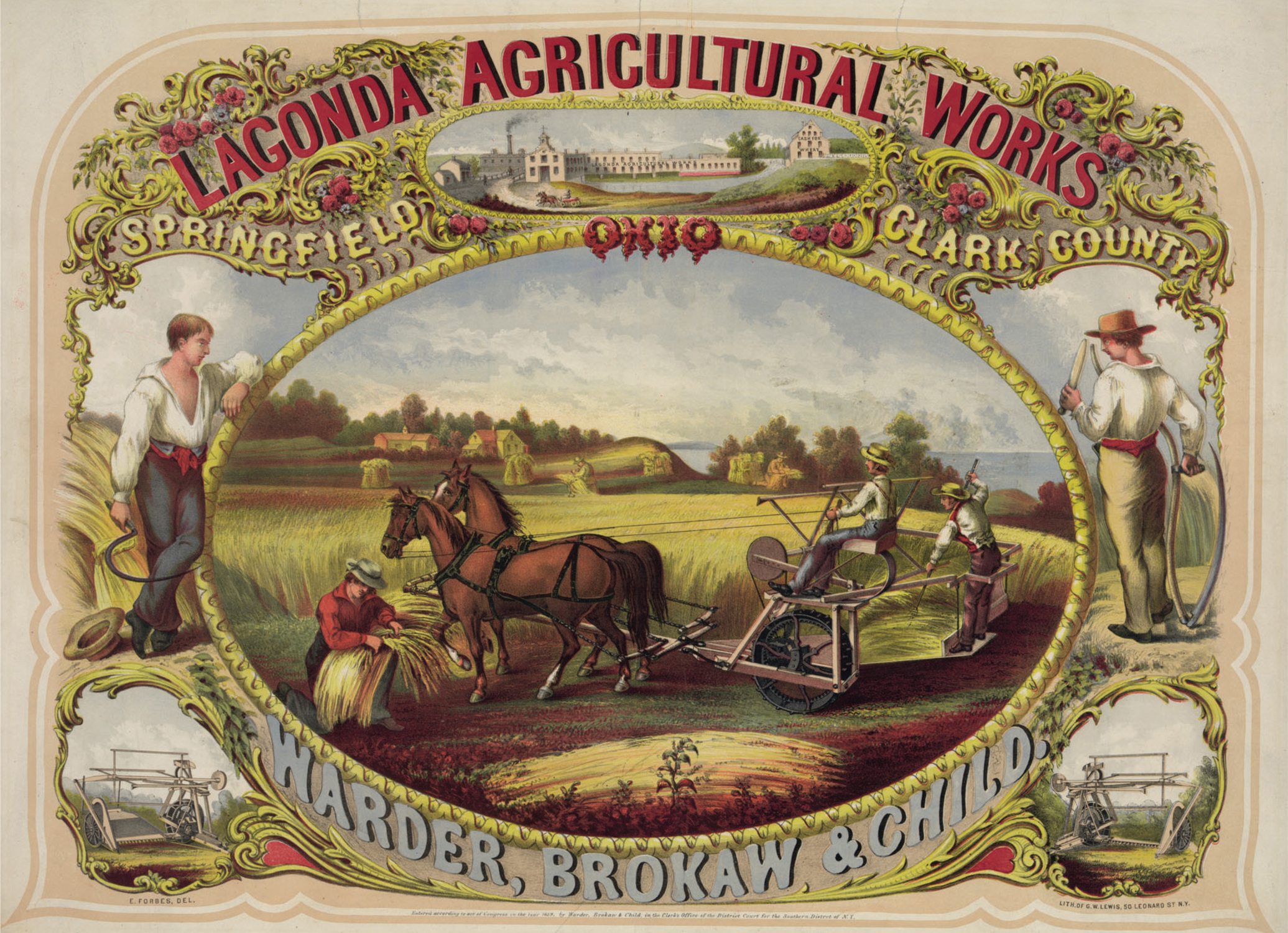

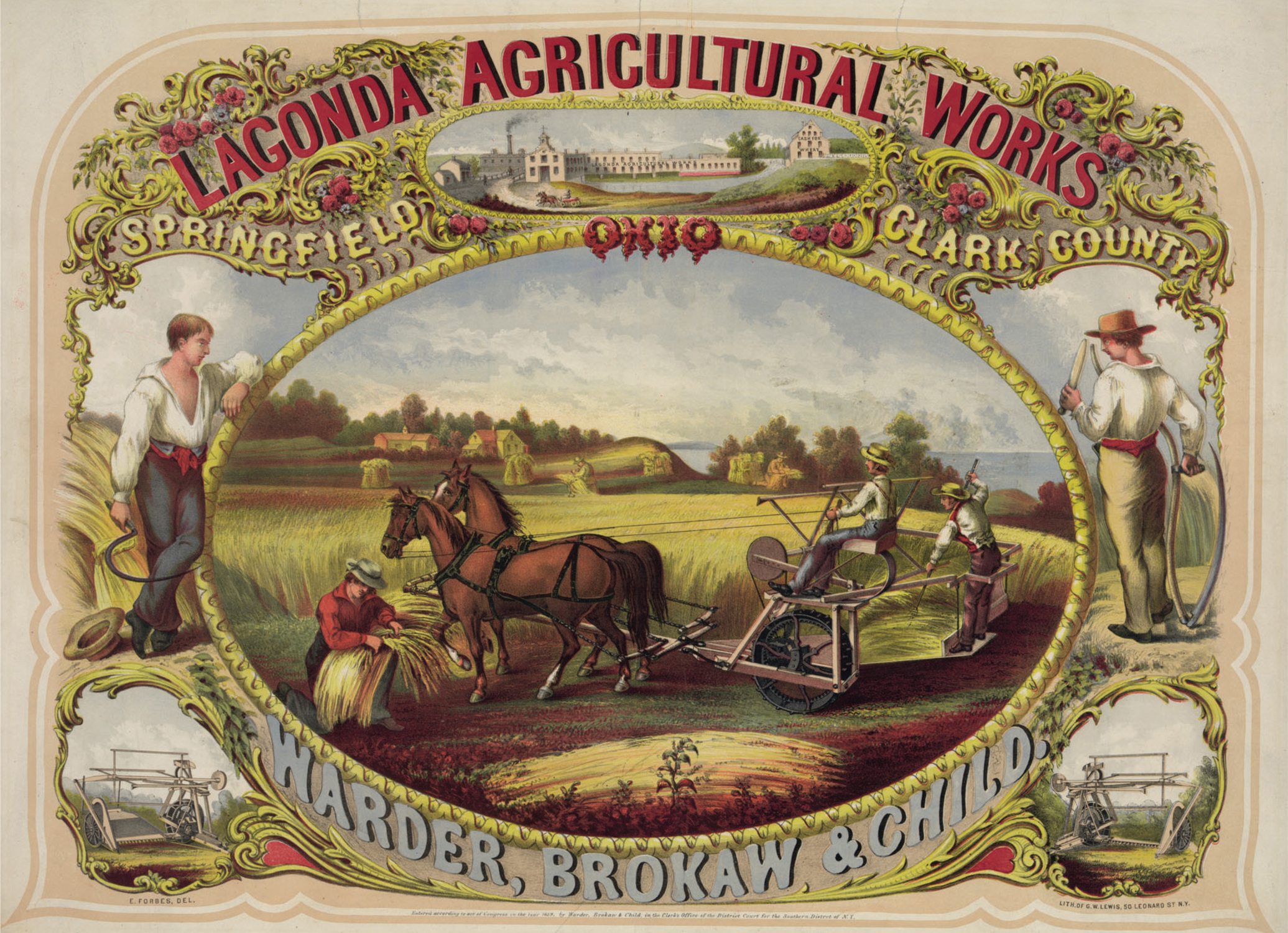

VISUAL ACTIVITY Mechanical Reaper Advertisement This advertisement for the mechanical reaper manufactured by the Lagonda Agricultural Works in Ohio illustrates the labor saved—and the labor still required—to harvest wheat. The revolving reel pulled the stalks of wheat toward a cutter and piled the cut grain on a platform. One man pushed the cut wheat onto the ground where another man bound into sheaves. Library of Congress. READING THE IMAGE: What kinds of labor are represented by the two men standing on each side of the oval picture of the reaper? What kinds of labor were saved by the mechanical reaper and what kinds were required? CONNECTIONS: How did reapers and other improvements increase agricultural productivity?

Federal land policy made possible the leap in agricultural productivity. Up to 1860, the United States continued to be land-rich and labor-poor. Territorial acquisitions made the nation a great deal richer in land, adding more than a billion acres with the Louisiana Purchase (see “The Louisiana Purchase” in chapter 10) and vast territories following the Mexican-American War. The federal government made most of this land available for purchase to attract settlers and to generate revenue. Millions of ordinary farmers bought federal land for just $1.25 an acre, or $50 for a forty-acre farm that could support a family. Millions of other farmers squatted on unclaimed federal land, and carved out farms. By making land available on relatively easy terms, federal land policy boosted the increase in agricultural productivity that fueled the nation’s impressive economic growth.