The American Promise:

Printed Page 356

HISTORICAL QUESTION

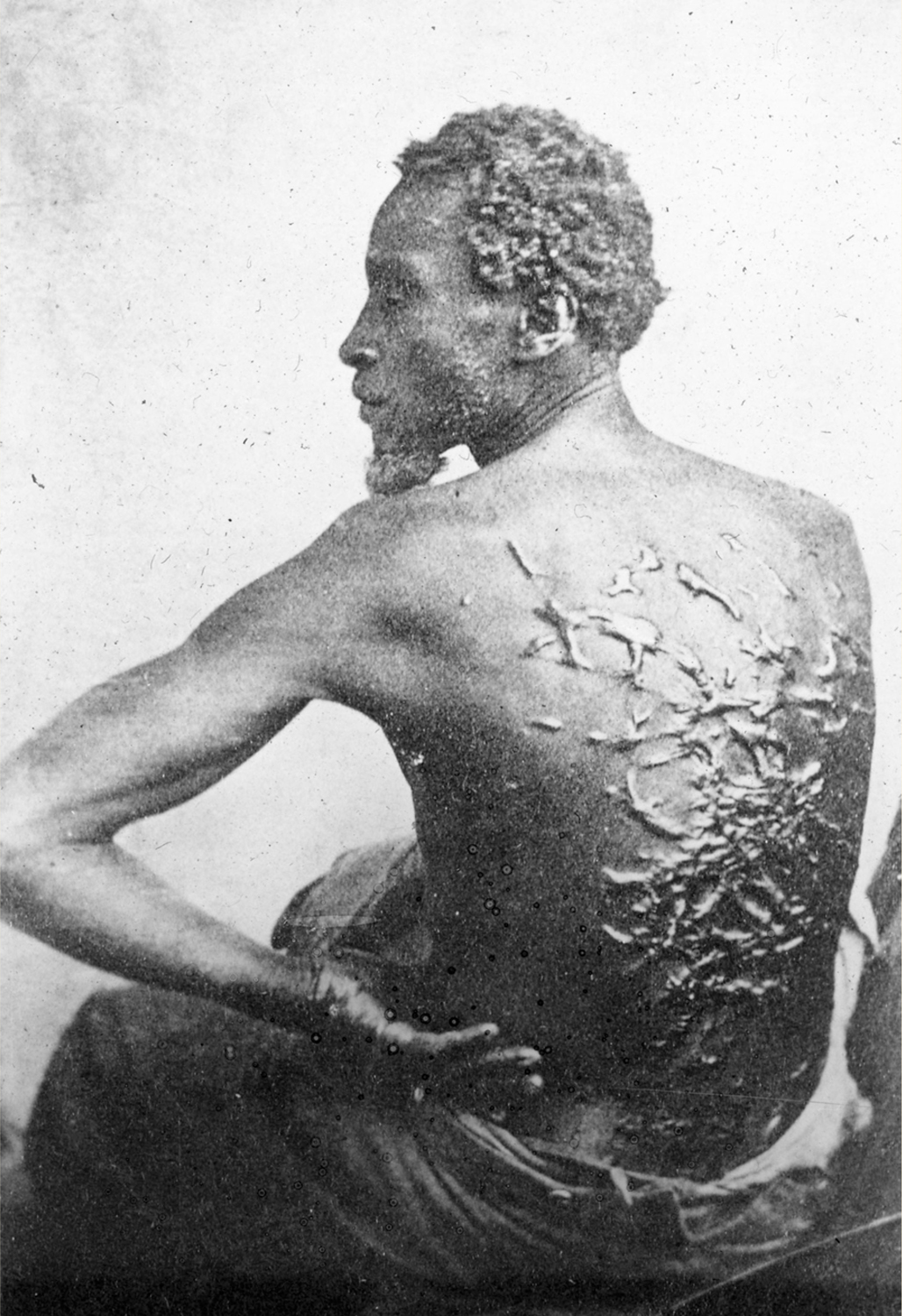

How Often Were Slaves Whipped?

There is little doubt that the whipping of slaves was widespread and acceptable in the South. We know from white sources that whipping was the prescribed method of physical punishment on most antebellum plantations. Masters’ instructions to overseers authorized whippings and often established the number of strokes an overseer could administer. Some planters allowed fifteen lashes, some fifty, and some one hundred. But slave owners’ instructions, as revealing as they are, tell us more about the severity of beating than about their frequency.

Remembrances of former slaves confirm that whipping was widespread and frequent. In the 1930s, a government program gathered testimony from more than 2,300 elderly African Americans about their experiences as slaves. Their accounts offer grisly evidence of the cruelty of slavery. “You say how did our Master treat his slaves?” asked one woman. “Scandalous, they treated them just like dogs.” She was herself whipped “till the blood dripped to the ground.” Bert Strong never personally felt the sting of the lash, but he recalled hearing slaves on other farms “hollering when they get beat.” He said, “They beat them till it a pity.” Beatings occurred often, but how often?

The diary of Bennet H. Barrow, the master of Highland plantation in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana, provides a rare picture of a master’s punishment of his slaves. For a twenty-

In most instances, Barrow recorded not only the fact of a whipping but also his reasons for administering it. All sorts of “rascallity” made Barrow reach for his whip. The provocations included family quarrels in the slave quarter, impudence, running away, and failure to keep curfew. But nearly 80 percent of the reasons were related to poor work. Barrow gave beatings for picking “very trashy cotton,” for “not picking as well as he can,” and for failing to pick the prescribed weight of cotton. One slave claimed to have lost his eyesight and for months refused to work, until Barrow “gave him 25 cuts yesterday morning & ordered him to work Blind or not.” Some planters used whips that raised welts, caused blisters, and bruised. Others resorted to rawhide and cowhide whips that broke the skin, caused scarring, and sometimes permanently maimed. Occasionally, slaves were beaten to death.

Whipping was not Barrow’s only means of inflicting pain. His diary mentions confining slaves to a plantation jail, putting them in chains, shooting them, breaking a “sword cane” over one slave’s head, having slaves mauled by dogs, placing them in stocks, “staking down” slaves for hours, holding their heads under water, and a variety of punishments intended to ridicule and to shame, including making men wear women’s clothing and do “women’s work,” such as the laundry. Still, Barrow’s preferred instrument of punishment was the whip.

On the Barrow plantation, as on many others, whipping was public. Victims were often tied to a stake in the quarter, and the other slaves were made to watch. In a real sense, the entire slave population on the plantation experienced a whipping every four and a half days, and all were familiar with its terror and agony.

Was whipping effective? Did it produce a hardworking, efficient, and conscientious labor force? Not according to Barrow’s own record. No evidence indicates that whipping changed the slaves’ behavior. What Barrow considered bad work continued. Unabated whipping is itself evidence of the failure of punishment to achieve the master’s will. Slaves knew the rules, yet they continued to act “badly.” And they continued to suffer.

Did Barrow whip as often as other planters whipped? We simply do not know. Still, the Barrow evidence allows us to speculate profitably on the frequency of whipping by large planters. We do know that Barrow did not consider himself a cruel man. He bitterly denounced his neighbor as “the most cruel Master i ever knew of” for castrating three of his slaves. Like most whites, he believed that the lash was essential to get the work done, and he used it no more than he believed absolutely necessary. Still, Barrow’s whip fell on someone’s back every few days.

Questions for Consideration

- How could slaveholders, who increasingly saw themselves as “Christian guardians” to their slaves, have justified whipping them?

- Why do you suppose masters relied on whipping as the preferred form of punishment?

- Why do you suppose Barrow gave the overwhelming majority of whippings because of poor work?

Connect to the Big Idea

How did paternalism affect the quality of slaves’ living and working conditions?