The American Promise:

Printed Page 379

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 363

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

The spectacle of shackled African Americans being herded south seared the conscience of every Northerner who witnessed such a scene. But even more Northerners were turned against slavery by a novel. Harriet Beecher Stowe, a white Northerner who had never set foot on a plantation, made the South’s slaves into flesh-

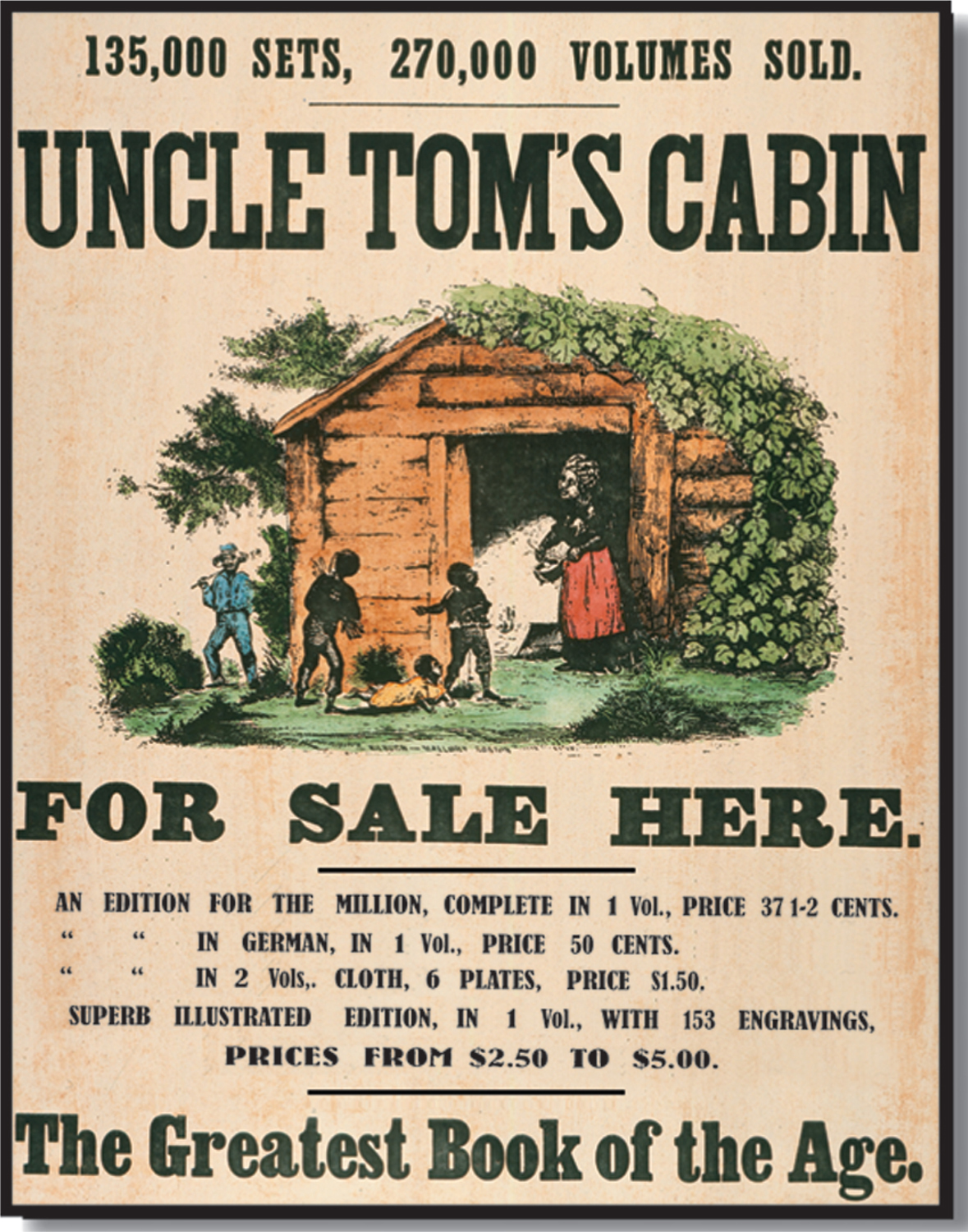

A member of a famous clan of preachers, teachers, and reformers, Stowe despised the slave catchers and wrote to expose the sin of slavery. Published as a book in 1852, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or Life among the Lowly, became a blockbuster hit, selling 300,000 copies in its first year and more than 2 million copies within ten years. Stowe’s characters leaped from the page. Here was the gentle slave Uncle Tom, a Christian saint who forgave those who beat him to death; the courageous slave Eliza, who fled with her child across the frozen Ohio River; and the fiendish overseer Simon Legree, whose Louisiana plantation was a nightmare of torture and death.

Stowe aimed her most powerful blows at slavery’s destructive impact on the family. Her character Eliza succeeds in keeping her son from being sold away, but other mothers are not so fortunate. When told that her infant has been sold, Lucy drowns herself. Driven half mad by the sale of a son and daughter, Cassy decides “never again [to] let a child live to grow up!” She gives her third child an opiate and watches as “he slept to death.” Northerners shed tears and sang praises to Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

What Northerners accepted as truth, Southerners denounced as slander. The Virginian George F. Holmes proclaimed Stowe a member of the “Woman’s Rights” and “Higher Law” schools and dismissed the novel as a work of “intense fanaticism.” The New Orleans Crescent called Stowe “part quack and part cutthroat,” a fake physician who came with arsenic in one hand and a pistol in the other to treat diseases she had “never witnessed.” Although it is impossible to measure precisely the impact of a novel on public opinion, Uncle Tom’s Cabin clearly helped to crystallize northern sentiment against slavery and to confirm white Southerners’ suspicion that they no longer received any sympathy in the free states.

Other writers—