The American Promise:

Printed Page 391

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 373

Chapter Chronology

The Lincoln-Douglas Debates

When Stephen Douglas learned that the Republican Abraham Lincoln would be his opponent for the Senate, he observed: “He is the strong man of the party—full of wit, facts, dates —and the best stump speaker, with his droll ways and dry jokes, in the West. He is as honest as he is shrewd, and if I beat him my victory will be hardly won.”

Not only did Douglas have to contend with a formidable foe, but the previous year, the nation’s economy had experienced a sharp downturn. Prices had plummeted, thousands of businesses had failed, and many were unemployed. As a Democrat, Douglas had to go before the voters as a member of the party whose policies stood accused of causing the panic of 1857.

Douglas’s response to another crisis in 1857, however, helped shore up his standing in Illinois. Proslavery forces in Kansas met in the town of Lecompton, drafted a proslavery constitution, and applied for statehood. Everyone knew that free-soilers outnumbered proslavery settlers, but President Buchanan instructed Congress to admit Kansas as the sixteenth slave state. Senator Douglas broke with the Democratic administration and denounced the Lecompton constitution; Congress killed the Lecompton bill. (When Kansans reconsidered the Lecompton constitution in an honest election, they rejected it six to one. Kansas entered the Union in 1861 as a free state.) By denouncing the fraudulent proslavery constitution, Douglas declared his independence from the South and, he hoped, made himself acceptable at home.

A relative unknown and a decided underdog in the Illinois election, Lincoln challenged Douglas to debate him face-to-face. The two met in seven communities for what would become a legendary series of debates. To the thousands who stood straining to see and hear, they must have seemed an odd pair. Douglas was five feet four inches tall, broad, and stocky; Lincoln was six feet four, angular, and lean. Douglas was in perpetual motion, darting across the platform, shouting, and jabbing the air; Lincoln stood still and spoke deliberately. Douglas wore the latest fashion and dazzled audiences with his flashy vests. Lincoln wore good suits but managed to look rumpled anyway.

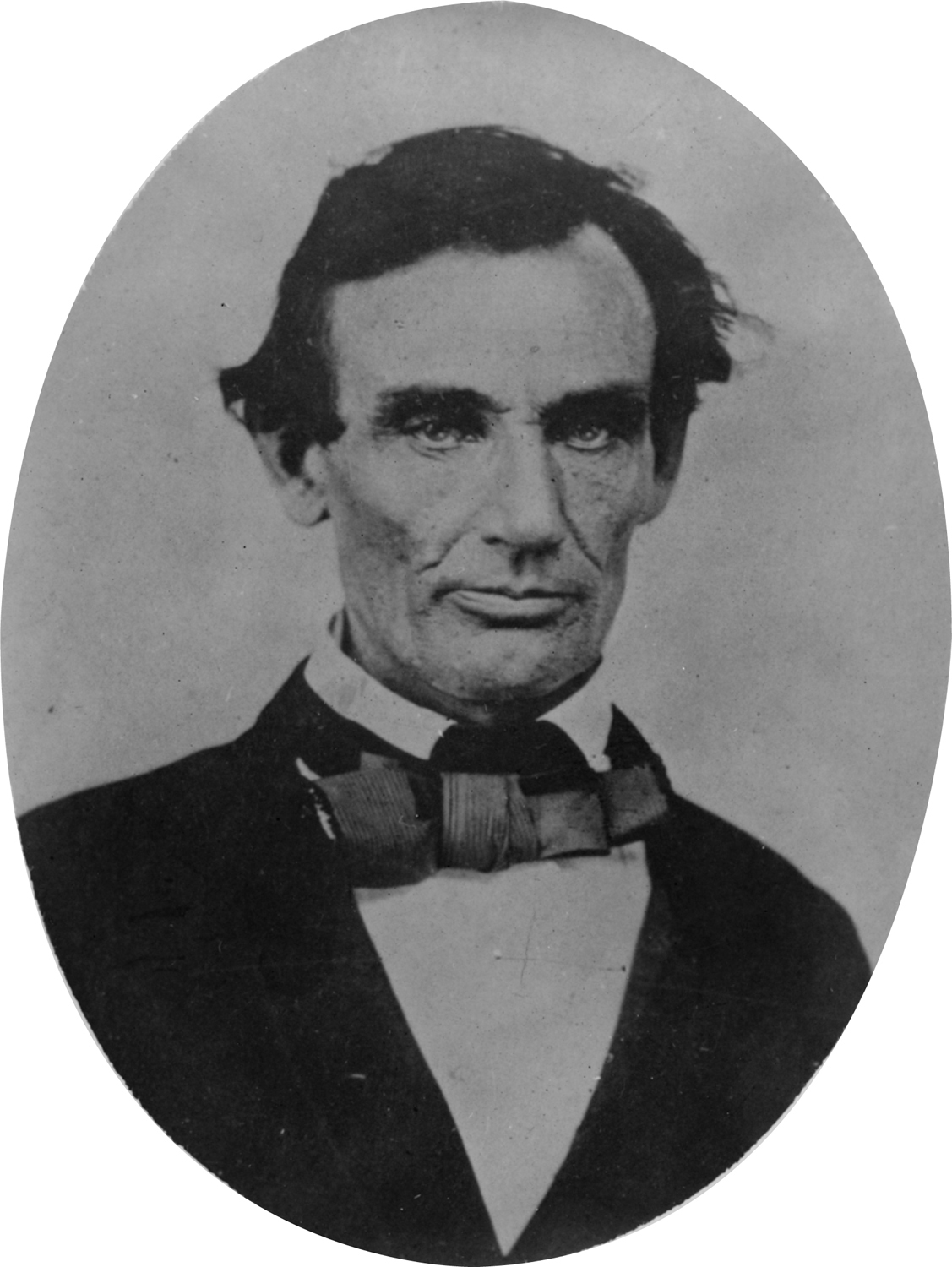

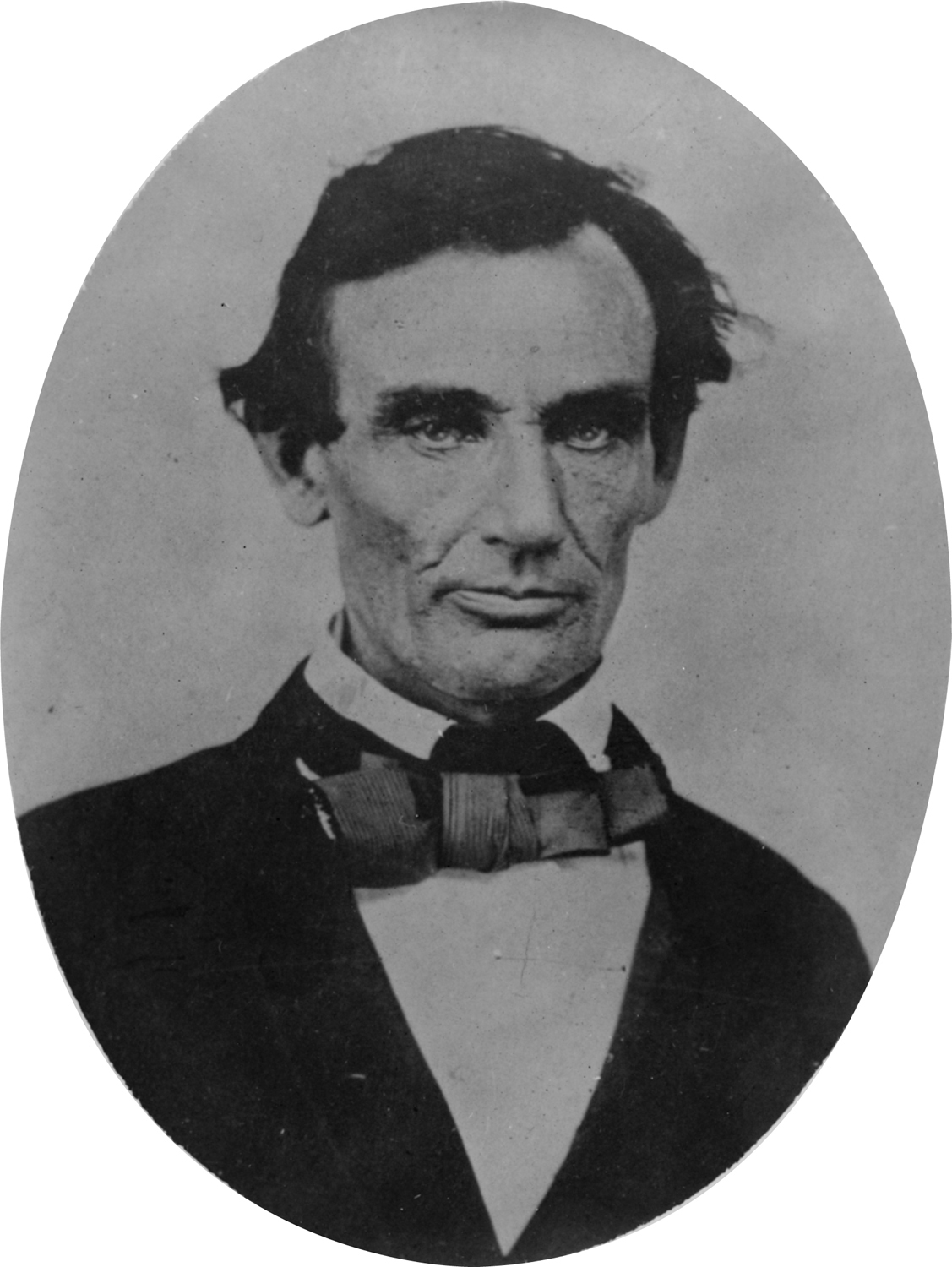

Abraham Lincoln (1858) This photograph was taken in Pittsfield, Illinois, two weeks before the final Lincoln-Douglas debate. It portrays Lincoln as an intense and focused campaigner, a man intent on forcing Douglas to debate the central issue—the morality of slavery. Library of Congress.

The two men debated the crucial issues of the age—slavery and freedom. Lincoln badgered Douglas with the question of whether he favored the spread of slavery. He tried to force Douglas into the damaging admission that the Supreme Court had repudiated Douglas’s own territorial solution, popular sovereignty. At Freeport, Illinois, Douglas admitted that settlers could not now pass legislation barring slavery, but he argued that they could ban slavery just as effectively by not passing protective laws, such as those found in slave states. Southerners condemned Douglas’s “Freeport Doctrine” and charged him with trying to steal the victory they had gained with the Dred Scott decision. Lincoln chastised his opponent for his “don’t care” attitude about slavery, for “blowing out the moral lights around us.”

Douglas worked the racial issue. He called Lincoln an abolitionist and an egalitarian enamored of “our colored brethren.” Put on the defensive, Lincoln reaffirmed his faith in white rule: “I will say, then, that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black race.” But unlike Douglas, who told racist jokes, Lincoln was no negrophobe. He tried to steer the debate back to what he considered the true issue: the morality and future of slavery. “Slavery is wrong,” Lincoln repeated, because “a man has the right to the fruits of his own labor.”

As Douglas predicted, the election was hard-fought and closely contested. Until the adoption of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1911, citizens voted for state legislators, who in turn selected U.S. senators. Since Democrats won a slight majority in the Illinois legislature, the members returned Douglas to the Senate. But the Lincoln-Douglas debates thrust Lincoln, the prairie Republican, into the national spotlight.

REVIEW Why did the Dred Scott decision strengthen northern suspicions of a “Slave Power” conspiracy?