The American Promise:

Printed Page 393

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 375

Republican Victory in 1860

When the Democrats converged on Charleston for their convention in April 1860, fire-

When bolting southern Democrats reconvened, they approved a platform with a federal slave code and nominated Vice President John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky. Southern moderates, however, refused to support Breckinridge. They formed the Constitutional Union Party to provide voters with a Unionist choice. Instead of adopting a platform and confronting the slavery question, the Constitutional Union Party merely approved a vague resolution pledging “to recognize no political principle other than the Constitution . . .

The Republicans smelled victory, but they needed to carry nearly all the free states to win. To make their party more appealing, they expanded their platform beyond antislavery. They hoped that free homesteads, a protective tariff, a transcontinental railroad, and a guarantee of immigrant political rights would provide an agenda broad enough to unify the North. While reasserting their commitment to stop the spread of slavery, they also denounced John Brown’s raid as “among the gravest of crimes” and confirmed the security of slavery in the South.

The foremost Republican, William H. Seward, had made enemies with his radical “higher law” doctrine, which claimed that there was a higher moral law than the Constitution, and with his “irrepressible conflict” speech, in which he declared that North and South were fated to collide. Lincoln, however, since bursting onto the national scene in 1858 had demonstrated his clear purpose, good judgment, and solid Republican credentials. That, and his residence in Illinois, a crucial state, made him attractive to the party. On the third ballot, the delegates chose Lincoln. Defeated by Douglas in a state contest less than two years earlier, Lincoln now stood ready to take him on for the presidency.

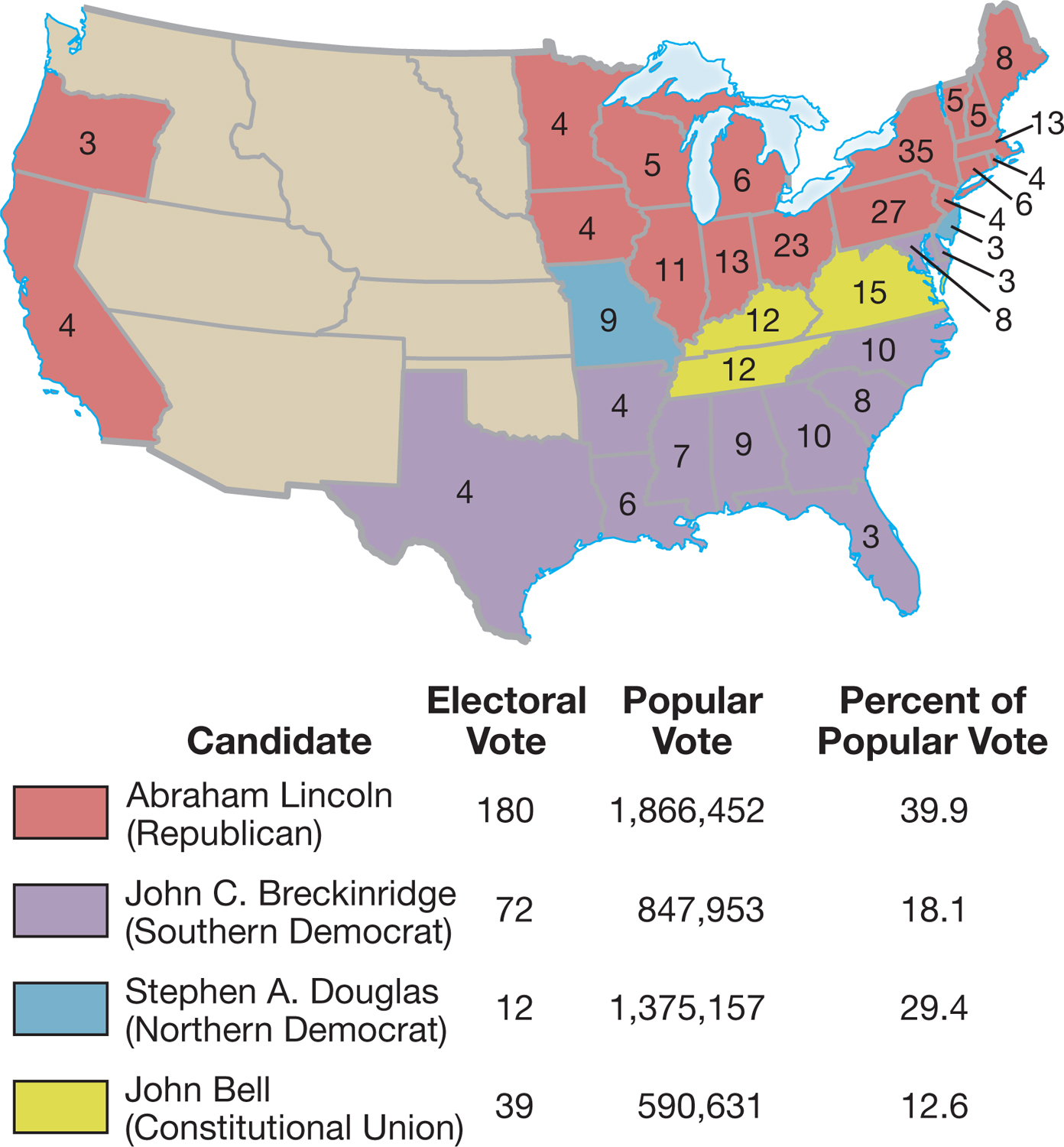

The election of 1860 was like none other in American politics. It took place in the midst of the nation’s severest crisis. Four major candidates crowded the presidential field. Rather than a four-

On November 6, 1860, Lincoln swept all of the eighteen free states except New Jersey, which split its electoral votes between him and Douglas. Although Lincoln received only 39 percent of the popular vote, he won easily in the electoral college with 180 votes, 28 more than he needed for victory (Map 14.5). Lincoln did not win because his opposition was splintered. Even if the votes of his three opponents had been combined, Lincoln still would have won. He won because his votes were concentrated in the free states, which contained a majority of electoral votes. Ominously, however, Breckinridge, running on a southern-