The American Promise:

Printed Page 376

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 360

Chapter Chronology

Debate and Compromise

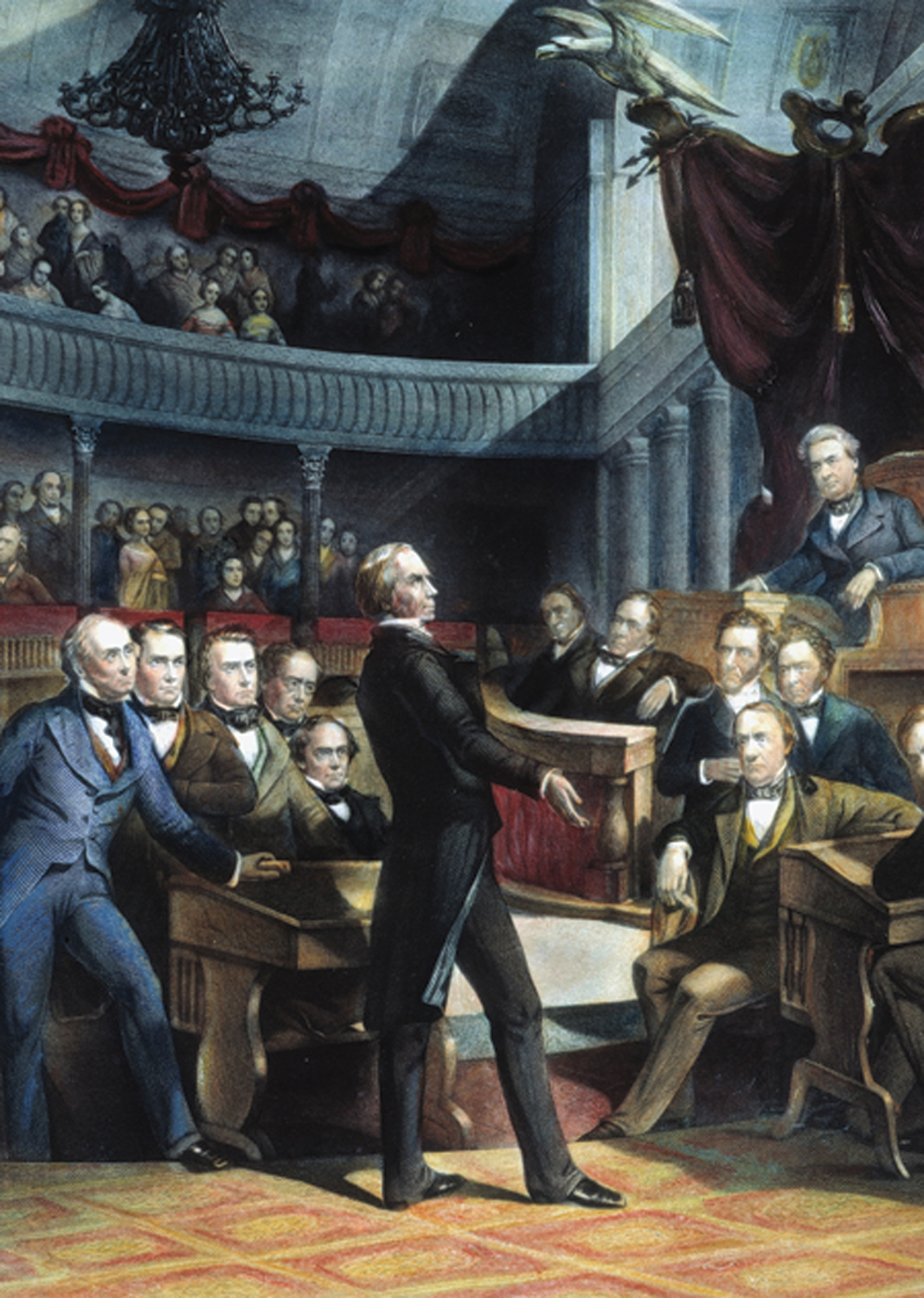

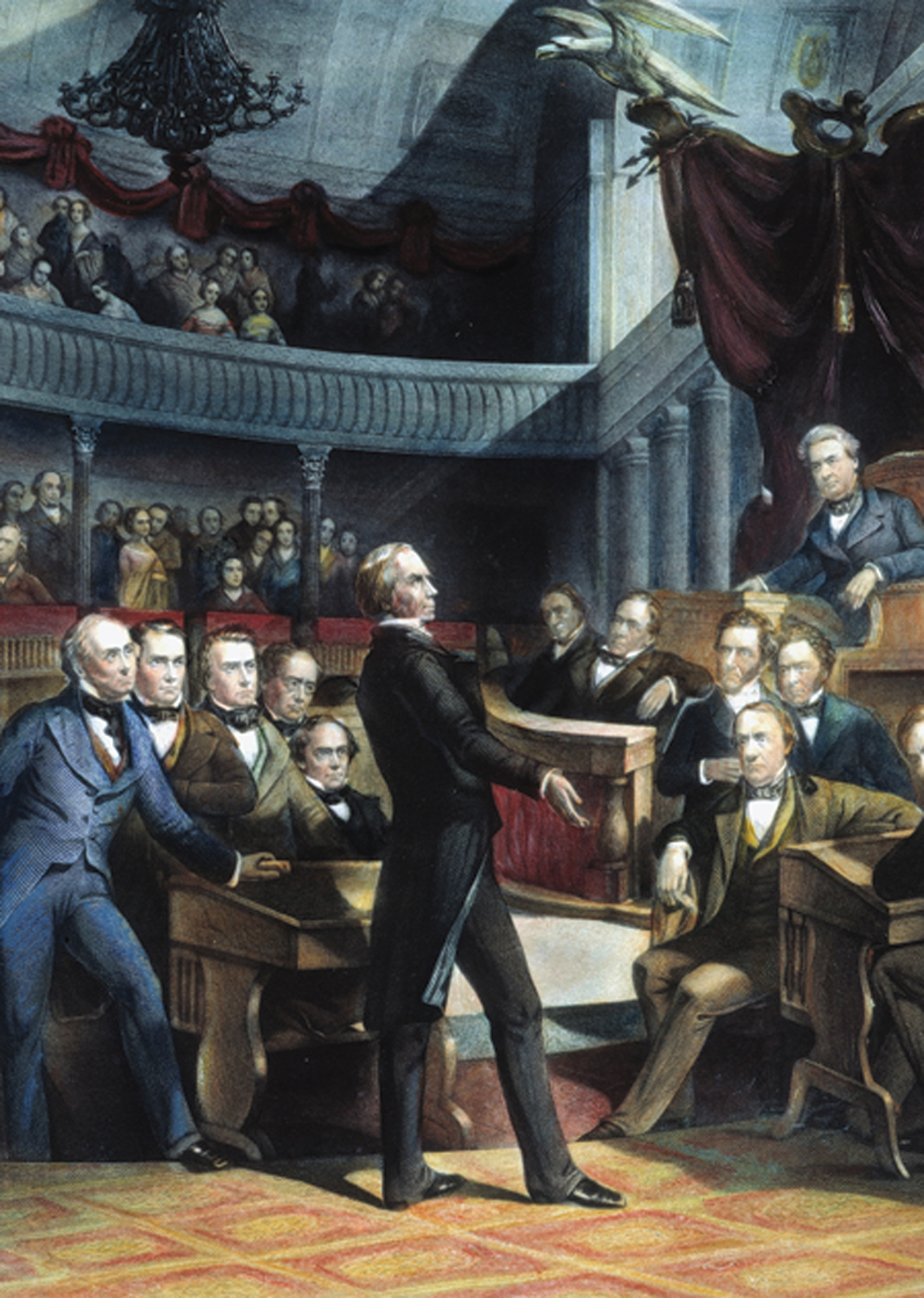

VISUAL ACTIVITY Henry Clay Offering His California Compromise to the Senate on 5 February 1850 Artist Peter F. Rothermel captures the high intensity of the seventy-three-year-old Kentuckian’s last significant political act. Citizens who packed the galleries of the U.S. Senate had come to hear the renowned orator explain that his package of compromises required mutual concessions from both North and South but no sacrifice of “great principle” from either. Friends called his performance the “crowning grace to his public life.” The Granger Collection, New York. READING THE IMAGE: What about the painting suggests either that the artist admired Clay and his effort for compromise or found his effort silly and wrongheaded? CONNECTIONS: How did Northerners and Southerners respond to Clay’s claim that his compromise required no sacrifice of “great principle”?

Zachary Taylor was very much a mystery when he entered the White House in March 1849. Almost immediately, the slaveholding president shocked the nation by championing a free-soil solution to the Mexican cession. Believing that he could avoid further sectional strife if California and New Mexico skipped the territorial stage, Taylor encouraged the settlers to apply for admission to the Union as states. Predominantly antislavery, the settlers began writing free-state constitutions. “For the first time,” Mississippian Jefferson Davis lamented, “we are about permanently to destroy the balance of power between the sections.”

Congress convened in December 1849, beginning one of the most contentious and most significant sessions in its history. President Taylor urged Congress to admit California as a free state immediately and to admit New Mexico, which lagged behind a few months, as soon as it applied. Southerners exploded. A North Carolinian declared that Southerners who would “consent to be thus degraded and enslaved, ought to be whipped through their fields by their own negroes.”

Into this rancorous scene stepped Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky, the architect of Union-saving compromises in the Missouri and nullification crises (see chapters 10 and 11). Clay offered a series of resolutions meant to answer and balance “all questions in controversy between the free and slave states, growing out of the subject of slavery.” Admit California as a free state, he proposed, but organize the rest of the Southwest without restrictions on slavery. Require Texas to abandon its claim to parts of New Mexico, but compensate it by assuming its preannexation debt. Abolish the domestic slave trade in Washington, D.C., but confirm slavery itself in the nation’s capital. Affirm Congress’s lack of authority to interfere with the interstate slave trade, and enact a more effective fugitive slave law.

Both antislavery advocates and “fire-eaters” (as radical Southerners who urged secession from the Union were called) savaged Clay’s plan. Senator Salmon P. Chase of Ohio ridiculed it as “sentiment for the North, substance for the South.” Senator Henry S. Foote of Mississippi denounced it as more offensive to the South than the speeches of abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, and Frederick Douglass combined. The most ominous response came from Calhoun, who argued that the fragile political unity of North and South depended on continued equal representation in the Senate, which Clay’s plan for a free California destroyed. “As things now stand,” he said in February 1850, the South “cannot with safety remain in the Union.”

Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster then addressed the Senate. Like Clay, Webster defended compromise. He told Northerners that the South had legitimate complaints, but he told Southerners that secession from the Union would mean civil war. He argued that the Wilmot Proviso’s ban on slavery in the territories was reckless and unnecessary because the harsh climate effectively prohibited the expansion of cotton and slaves into the new American Southwest. Why, then, “taunt” Southerners with the proviso? “I would not take pains uselessly to reaffirm an ordinance of nature, nor to reenact the will of God,” Webster declared.

Free-soil forces recoiled from what they saw as Webster’s desertion. Senator William H. Seward of New York responded that Webster’s and Clay’s compromise with slavery was “radically wrong and essentially vicious.” He rejected Calhoun’s argument that Congress lacked the constitutional authority to exclude slavery from the territories. In any case, Seward said, there was a “higher law than the Constitution”—the law of God—to ensure freedom in all the public domain. Claiming that God was a Free-Soiler did nothing to cool the superheated political atmosphere.

In May 1850, the Senate considered a bill that joined Clay’s resolutions into a single comprehensive package. Clay bet that a majority of Congress wanted compromise and that the members would vote for the package, even though it contained provisions they disliked. But the strategy backfired. Free-Soilers and proslavery Southerners voted down the comprehensive plan.

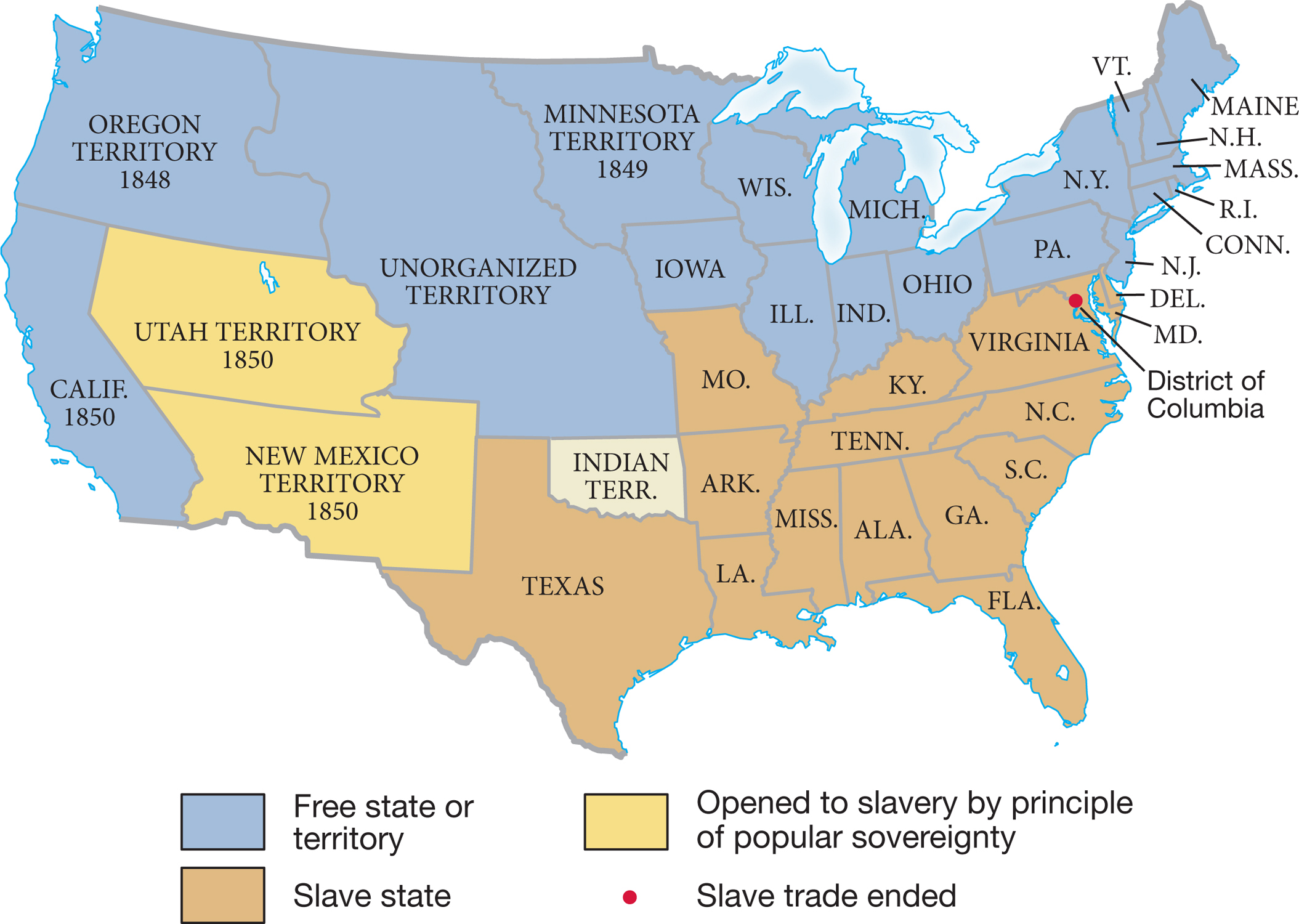

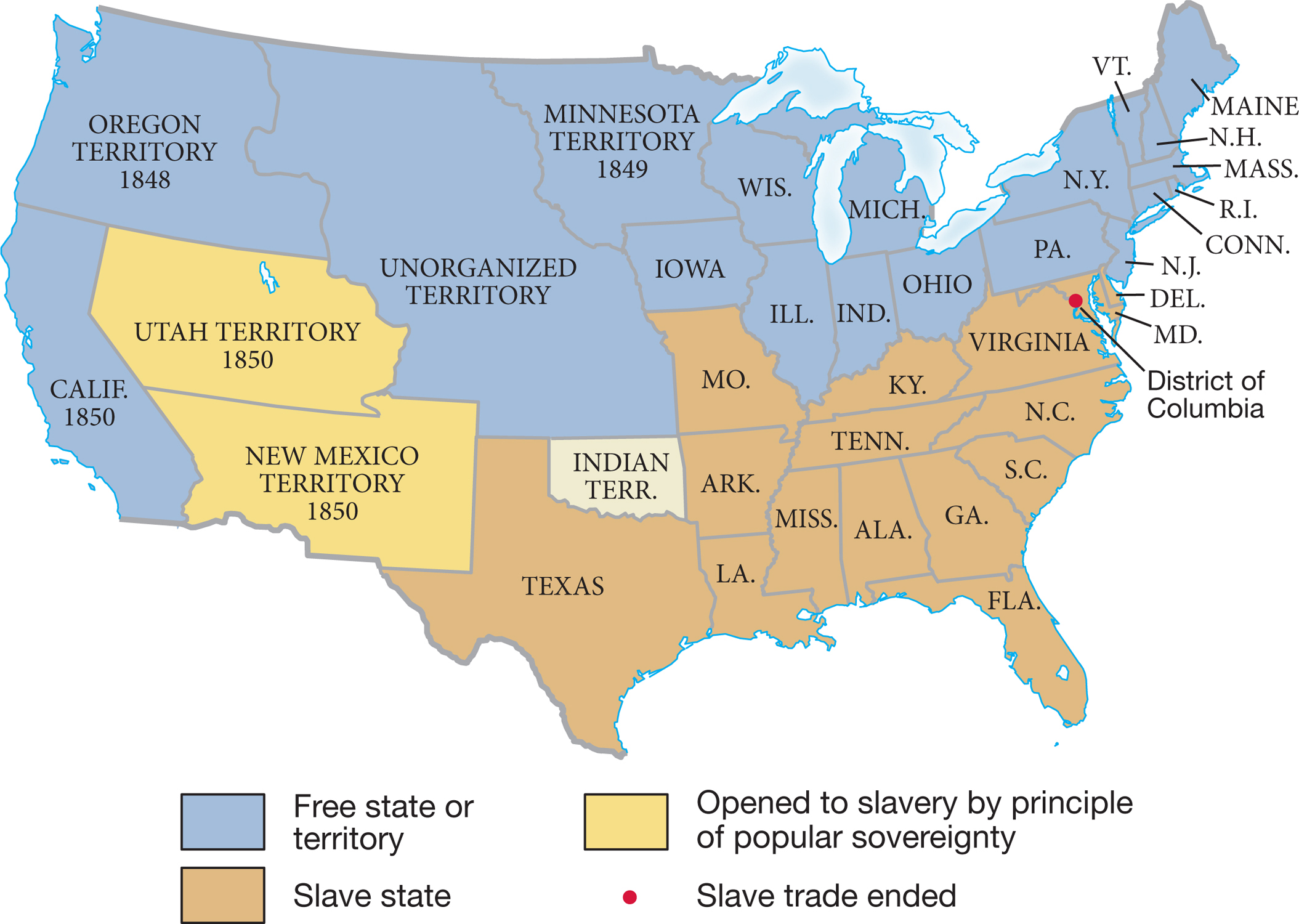

MAP 14.2 The Compromise Of 1850 The patched-together sectional agreement was both clumsy and unstable. Few Americans—in either North or South—supported all five parts of the Compromise.

Fortunately for those who favored a settlement, Senator Stephen A. Douglas, a rising Democratic star from Illinois, broke the bill into its parts and skillfully ushered each through Congress. The agreement Douglas won in September 1850 was very much the one Clay had proposed in January. California entered the Union as a free state. New Mexico and Utah became territories where slavery would be decided by popular sovereignty. Texas accepted its boundary with New Mexico and received $10 million from the federal government. Congress ended the slave trade in the District of Columbia but enacted a more stringent fugitive slave law. In September, Millard Fillmore, who had become president when Zachary Taylor died in July, signed into law each bill, collectively known as the Compromise of 1850 (Map 14.2).

The nation breathed a sigh of relief, for the Compromise preserved the Union and peace for the moment. But as some understood, the Compromise of 1850 was not a true compromise at all. Douglas’s parliamentary skill, not a spirit of conciliation, was responsible for the legislative success. The Compromise scarcely touched the deep conflict over slavery. Free-Soiler Salmon Chase observed, “The question of slavery in the territories has been avoided. It has not been settled.”

REVIEW How might the Compromise of 1850 have eased sectional tensions?