The American Promise:

Printed Page 406

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 390

Chapter Chronology

Stalemate in the Eastern Theater

In the summer of 1861, Lincoln ordered the 35,000 Union troops assembling outside Washington to attack the 20,000 Confederates defending Manassas, a railroad junction in Virginia about thirty miles southwest of Washington. On July 21, the army forded Bull Run, a branch of the Potomac River, and engaged the southern forces (Map 15.2). But fast-moving southern reinforcements blunted the Union attack and then counterattacked. What began as an orderly Union retreat turned into a panicky stampede.

MAP ACTIVITY Map 15.2 The Civil War, 1861–1862 While most eyes were focused on the eastern theater, especially the ninety-mile stretch of land between Washington, D.C., and the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, Union troops were winning strategic victories in the West. READING THE MAP: In which states did the Confederacy and the Union each win the most battles during this period? Which side used or followed water routes most for troop movements and attacks? CONNECTIONS: Which major cities in the South and West fell to Union troops in 1862? Which strategic area did those Confederate losses place in Union hands? How did this outcome affect the later movement of troops and supplies?

By Civil War standards, the casualties (wounded and dead) at the battle of Bull Run (or Manassas, as Southerners called the battle) were light, about 2,000 Confederates and 1,600 Federals. The significance of the battle lay in the lessons Northerners and Southerners drew from it. For Southerners, it confirmed the superiority of rebel fighting men and the inevitability of Confederate nationhood. Manassas was “one of the decisive battles of the world,” a Georgian proclaimed. It “has secured our independence.” On the other hand, defeat sobered Northerners. It was a major setback, admitted the New York Tribune, but “let us go to work, then, with a will.” Within four days of the disaster, the president authorized the enlistment of 1 million men for three years.

Peninsula Campaign, 1862

Lincoln also found a new general, the young George B. McClellan, whom he appointed commander of the newly named Army of the Potomac. Having graduated from West Point second in his class, the thirty-four-year-old McClellan believed that he was a great soldier and that Lincoln was a dunce, the “original Gorilla.” A superb administrator and organizer, McClellan energetically whipped his dispirited soldiers into shape, but for all his energy, McClellan lacked decisiveness. Lincoln wanted a general who would advance, take risks, and fight, but McClellan went into winter quarters. “If General McClellan does not want to use the army I would like to borrow it,” Lincoln declared in frustration.

Finally, in May 1862, McClellan launched his long-awaited offensive. He transported his highly polished army, now 130,000 strong, to the mouth of the James River and began slowly moving up the Yorktown peninsula toward Richmond. When he was within six miles of the Confederate capital, General Joseph Johnston hit him like a hammer. In the assault, Johnston was wounded and was replaced by Robert E. Lee, who would become the South’s most celebrated general. Lee named his command the Army of Northern Virginia.

The contrast between Lee and McClellan could hardly have been greater. McClellan brimmed with conceit; Lee was courteous and reserved. On the battlefield, McClellan grew timid and irresolute, and Lee became audaciously, even recklessly, aggressive. And Lee had at his side in the peninsula campaign military men of real talent: Thomas J. Jackson, nicknamed “Stonewall” for holding the line at Manassas, and James E. B. (“Jeb”) Stuart, a dashing twenty-nine-year-old cavalry commander who rode circles around Yankee troops.

Lee’s assault initiated the Seven Days Battle (June 25–July 1) and began McClellan’s march back down the peninsula. By the time McClellan reached safety, 30,000 men from both sides had died or been wounded. Although Southerners suffered twice the casualties of Northerners, Lee had saved Richmond. Lincoln fired McClellan and replaced him with General John Pope.

In August, north of Richmond, at the second battle of Bull Run, Lee’s smaller army battered Pope’s forces and sent them scurrying back to Washington. Lincoln ordered Pope to Minnesota to pacify the Indians and restored McClellan to command. Lincoln had not changed his mind about McClellan’s capacity as a warrior, but he had concluded, “There is no man in the Army who can lick these troops of ours into shape half as well as he. . . . If he can’t fight himself, he excels in making others ready to fight.”

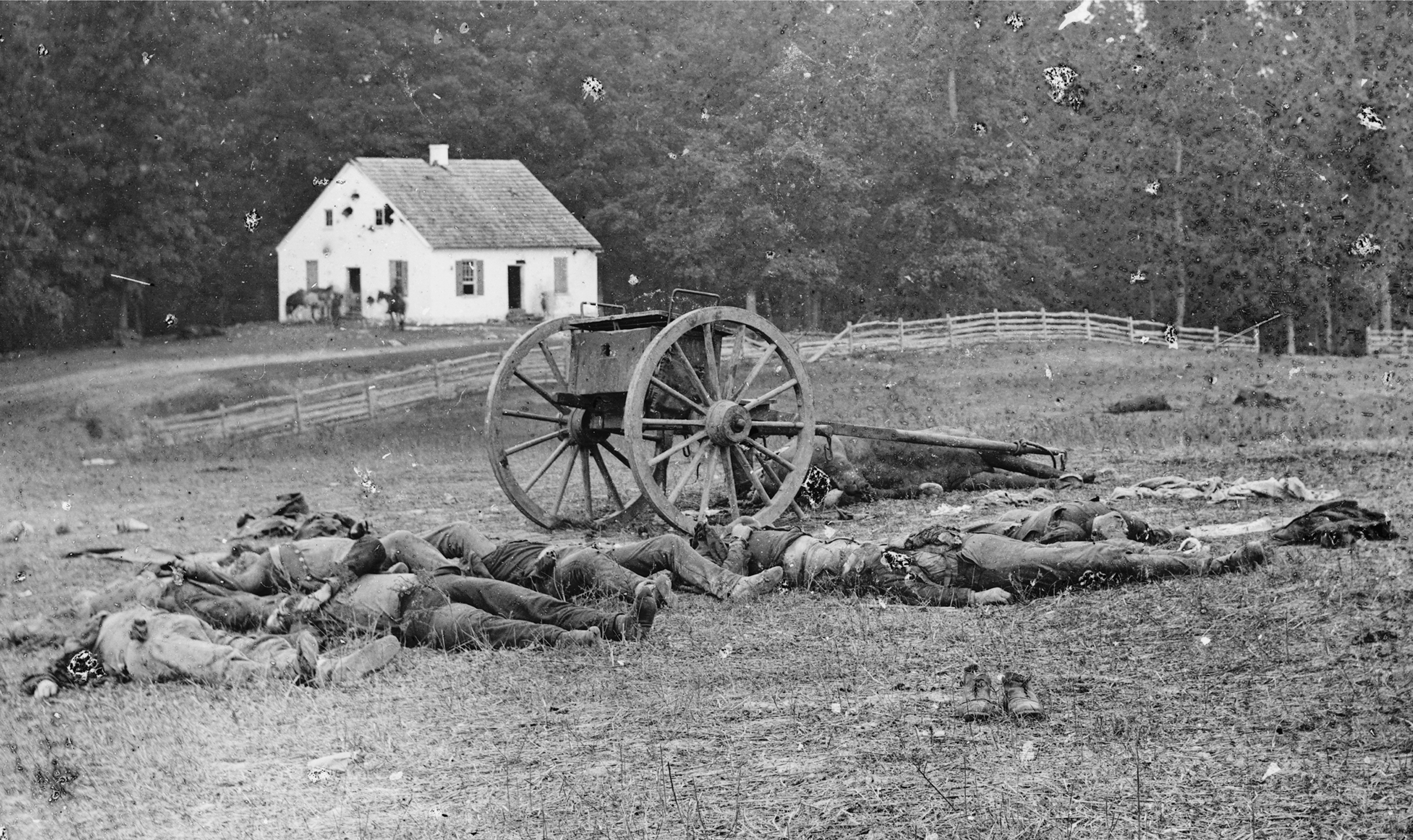

Believing that he had the enemy on the run, Lee pushed his army across the Potomac and invaded Maryland. A victory on northern soil would dislodge Maryland from the Union, Lee reasoned, and might even cause Lincoln to sue for peace. On September 17, 1862, McClellan’s forces engaged Lee’s army at Antietam Creek (see Map 15.2). With “solid shot . . . cracking skulls like eggshells,” according to one observer, the armies went after each other. At Miller’s Cornfield, the firing was so intense that “every stalk of corn in the . . . field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife.” By nightfall, 6,000 men lay dead or dying on the battlefield, and 17,000 more had been wounded. The battle of Antietam would be the bloodiest day of the war and sent the battered Army of Northern Virginia limping back home. McClellan claimed to have saved the North, but Lincoln again removed him from command of the Army of the Potomac and appointed General Ambrose Burnside.

The Dead of Antietam In October 1862, photographer Mathew Brady opened an exhibition that presented the battle of Antietam as the soldiers saw it. A New York Times reporter observed, “Mr. Brady has done something to bring to us the terrible reality and earnestness of the war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along [our] streets, he had done something very like it.” Library of Congress.

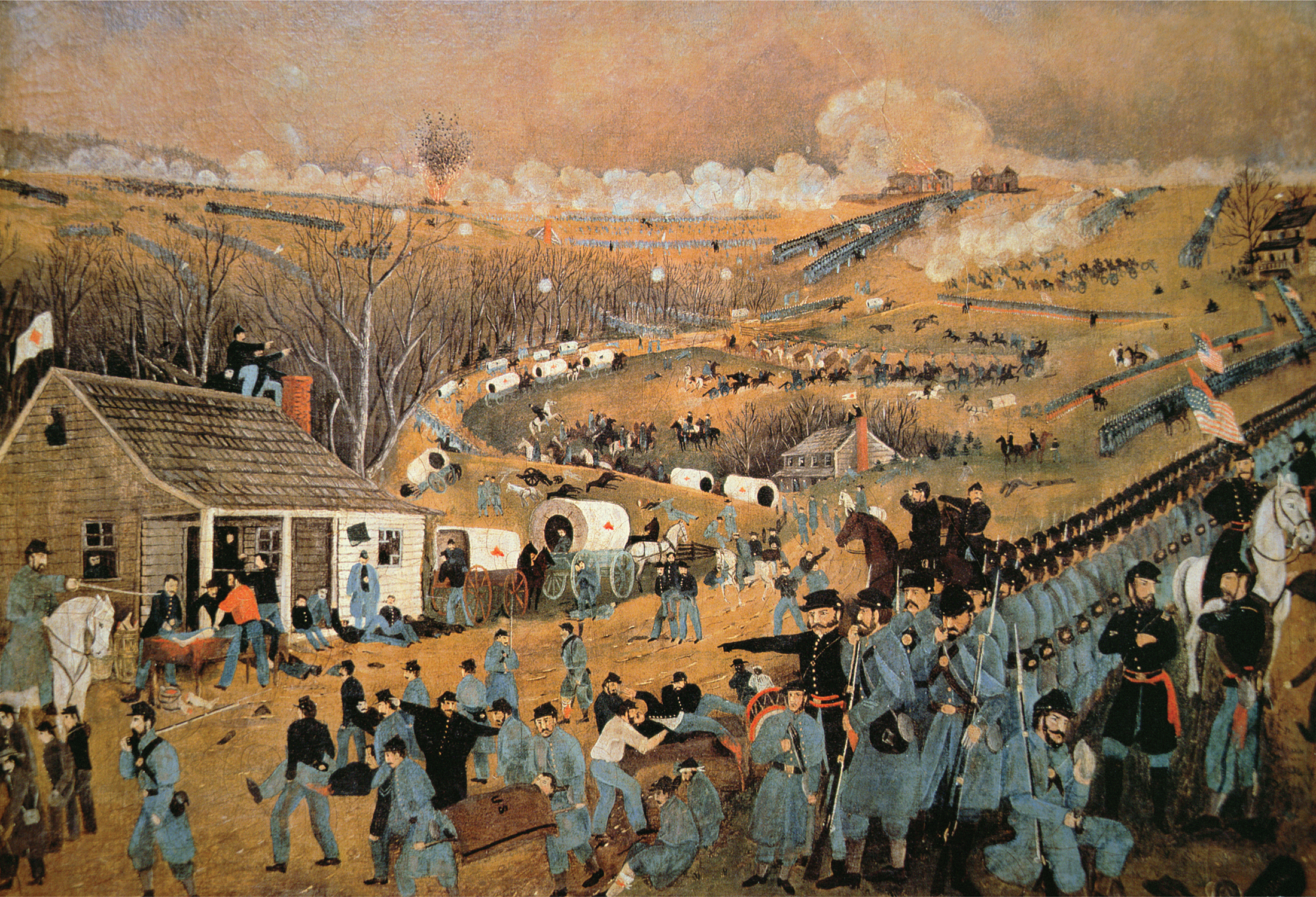

Though bloodied, Lee found an opportunity in December to punish the enemy at Fredericksburg, Virginia, where Burnside’s 122,000 Union troops faced 78,500 Confederates dug in behind a stone wall on the heights above the Rappahannock River. Half a mile of open ground separated the armies. “A chicken could not live on that field when we open on it,” a Confederate artillery officer predicted. Yet Burnside ordered a frontal assault. When the shooting ceased, the Federals counted nearly 13,000 casualties, the Confederates fewer than 5,000. The battle of Fredericksburg was one of the Union’s worst defeats. As 1862 ended, the North seemed no nearer to ending the rebellion than it had been when the war began. Rather than checkmate, military struggle in the East had reached stalemate.

VISUAL ACTIVITY Battle of Fredericksburg, 1862 This painting by Private John Richards (1831–1889) of the New York Volunteers captures the behind-the-lines Union activity at the battle of Fredericksburg. Long rows of fresh troops await orders to march up the hill to join the fighting underway in the distance. Barely visible, the cavalry charges off into one of the Union’s greatest failures. These foot soldiers will follow the cavalry soon. Private Collection/Peter Newark Military Pictures / The Bridgeman Art Library. READING THE IMAGE: What does the artist portray in the lower left of the painting? What are the lines of wagons hauling? CONNECTIONS: At Fredericksburg, General Ambrose Burnside joined the list of failed Union generals. What other Union defeats can be attributed, at least in part, to failed Union leadership?