The American Promise:

Printed Page 411

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 395

Chapter Chronology

International Diplomacy

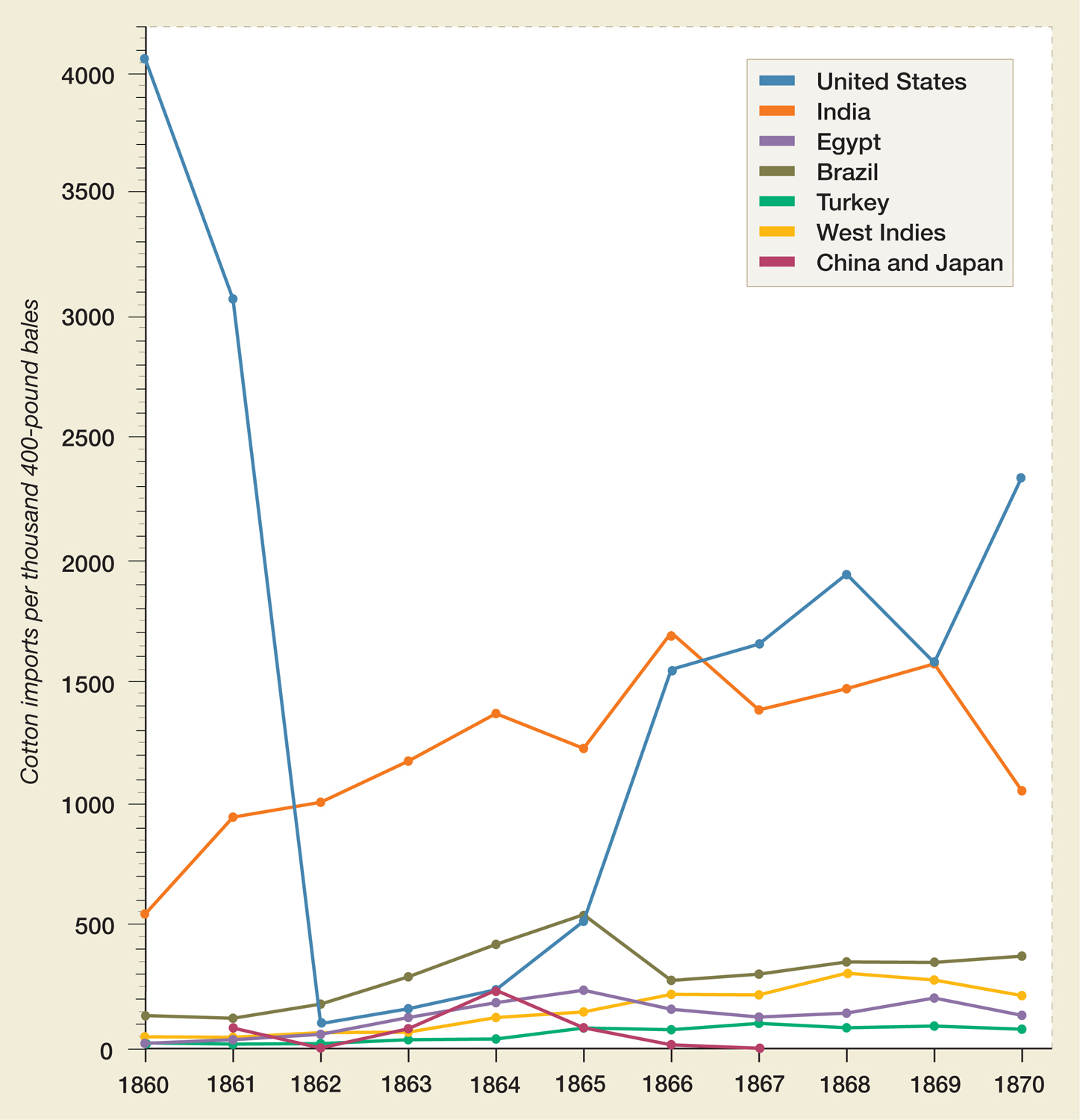

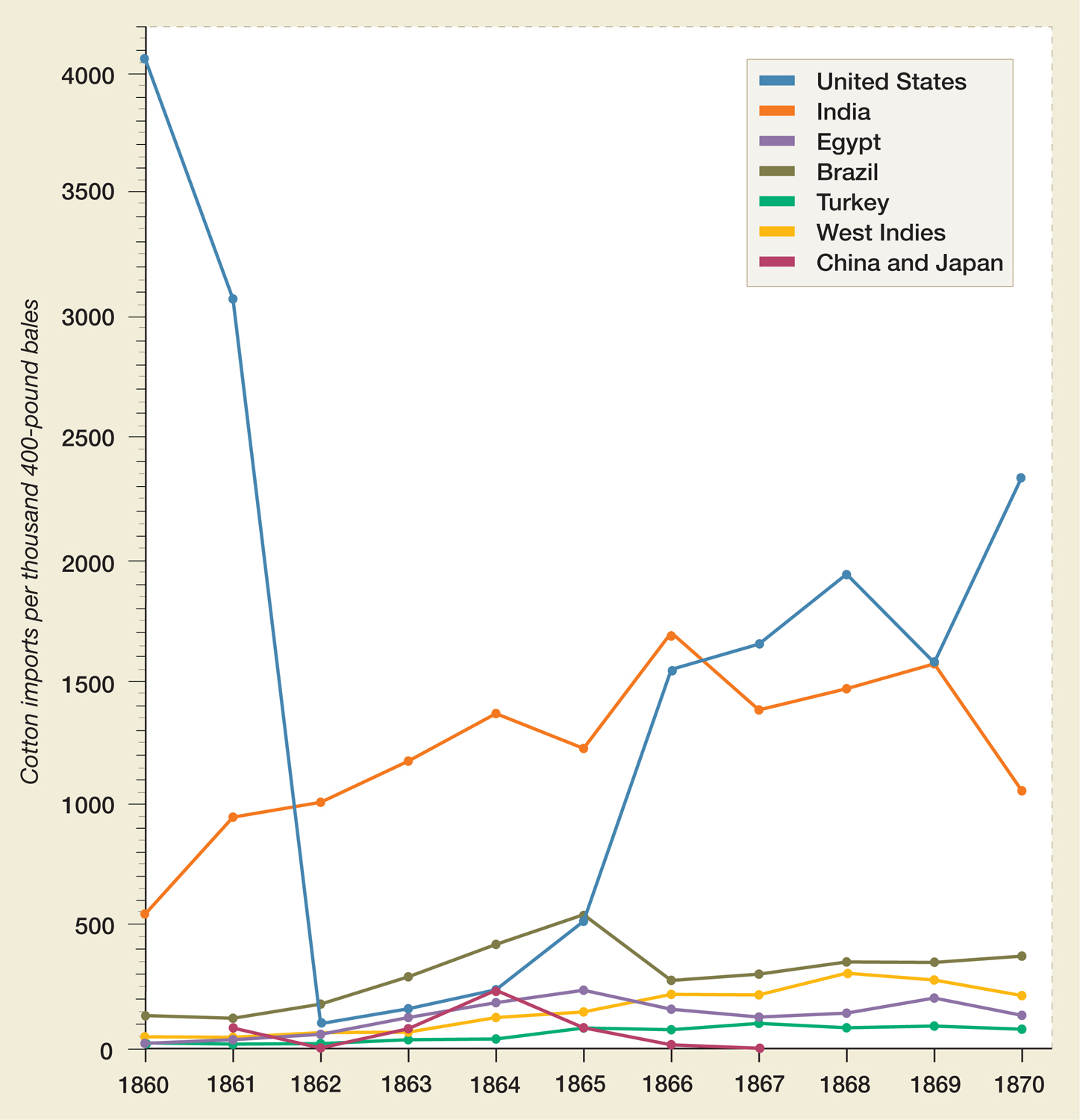

FIGURE 15.2 Global Comparison: European Cotton Imports, 1860–1870 In 1860, the South enjoyed a near monopoly in supplying cotton to Europe’s textile mills, but the Civil War almost entirely halted its exports. Figures for Europe’s importation of cotton for 1861 to 1865 reveal one of the reasons the Confederacy’s King Cotton diplomacy failed: Europeans found other sources of cotton. Which countries were most important in filling the void? When the war ended in 1865, cotton production resumed in the South, and exports to Europe again soared. Did the South regain its near monopoly? How would you characterize the United States’ competitive position five years after the war?

What the Confederates could not achieve on the seas, they sought to achieve through international diplomacy. They based their hope for European intervention on King Cotton. In theory, cotton-starved European nations would have no choice but to break the Union blockade and recognize the Confederacy. Southern hopes were not unreasonable, for at the height of the “cotton famine” in 1862, when 2 million British workers were unemployed, Britain tilted toward recognition. Along with several other European nations, Britain granted the Confederacy “belligerent” status, which enabled it to buy goods and build ships in European ports. But no country challenged the Union blockade or recognized the Confederate States of America as a nation, a bold act that probably would have drawn that country into war.

King Cotton diplomacy failed for several reasons. A bumper cotton crop in 1860 meant that the warehouses of British textile manufacturers bulged with surplus cotton throughout 1861. In 1862, when a cotton shortage did occur, European manufacturers found new sources in India, Egypt, and elsewhere (Figure 15.2). In addition, the development of a brisk trade between the Union and Britain—British war material for American grain and flour—helped offset the decline in textiles and encouraged Britain to remain neutral.

Europe’s temptation to intervene disappeared for good in 1862. Union military successes in the West made Britain and France think twice about linking their fates to the struggling Confederacy. Moreover, in September 1862, Lincoln announced a new policy that made an alliance with the Confederacy an alliance with slavery—a commitment the French and British, who had outlawed slavery in their empires and looked forward to its eradication worldwide, were not willing to make. After 1862, the South’s cause was linked irrevocably with slavery and reaction, and the Union’s cause was linked with freedom and democracy. The Union, not the Confederacy, had won the diplomatic stakes.

REVIEW Why did the Confederacy’s bid for international support fail?