The American Promise:

Printed Page 414

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 399

The War of Black Liberation

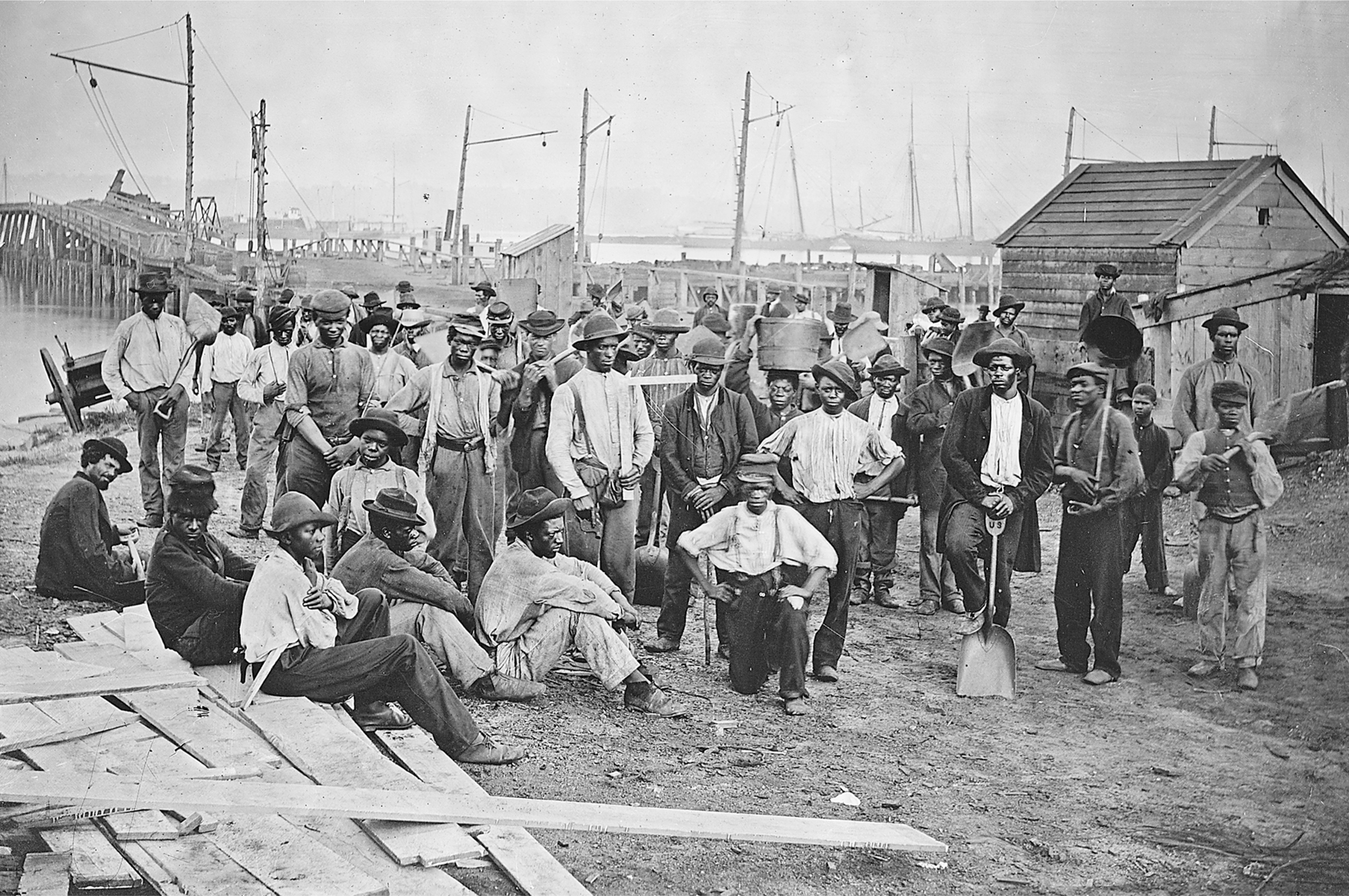

Even before Lincoln proclaimed emancipation a Union war aim, African Americans in the North had volunteered to fight. Military service, one black volunteer declared, would mean “the elevation of a downtrodden and despised race.” But the War Department, doubtful of blacks’ abilities and fearful of white reaction to serving side by side with them, refused to make black men soldiers. Instead, the army employed black men as manual laborers; black women sometimes found employment as laundresses and cooks. The navy, however, accepted blacks from the outset, including runaway slaves such as William Gould (see the introduction to this chapter).

As Union casualty lists lengthened, Northerners gradually and reluctantly turned to African Americans to fill the army’s blue uniforms. With the Militia Act of July 1862, Congress authorized enrolling blacks in “any military or naval service for which they may be found competent.” After the Emancipation Proclamation, whites—

The military was far from color-

In time, whites allowed blacks to put down their shovels and to shoulder rifles. At the battles of Port Hudson and Milliken’s Bend on the Mississippi River and at Fort Wagner in Charleston harbor, black courage under fire finally dispelled notions that African Americans could not fight. More than 38,000 black soldiers died in the Civil War, a mortality rate that was higher than that of white troops. Blacks played a crucial role in the triumph of the Union and the destruction of slavery in the South. (See “Seeking the American Promise.”)

From the beginning, African Americans viewed the Civil War as a revolutionary struggle to overthrow slavery and to gain equality for their entire race. “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S.; let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket,” Frederick Douglass predicted, “and there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship.” When black men became soldiers, they and their families gained new confidence and self-

REVIEW How did the war for union become a war for black freedom?