The American Promise:

Printed Page 444

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 423

The Fourteenth Amendment and Escalating Violence

In June 1866, Congress passed the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, and two years later the states ratified it. The most important provisions of this complex amendment made all native-

The Fourteenth Amendment also dealt with voting rights. It gave Congress the right to reduce the congressional representation of states that withheld suffrage from some of its adult male population. In other words, white Southerners could either allow black men to vote or see their representation in Washington slashed. Whatever happened, Republicans stood to benefit from the Fourteenth Amendment. If southern whites granted voting rights to freedmen, Republicans would gain valuable black votes. If whites refused, the representatives of southern Democrats would plunge.

The Fourteenth Amendment’s suffrage provisions ignored the small band of women who had emerged from the war demanding “the ballot for the two disenfranchised classes, negroes and women.” Founding the American Equal Rights Association in 1866, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton lobbied for “a government by the people, and the whole people; for the people and the whole people.” They felt betrayed when their old antislavery allies refused to work for their goals. “It was the Negro’s hour,” Frederick Douglass explained. Senator Charles Sumner suggested that woman suffrage could be “the great question of the future.”

The Fourteenth Amendment provided for punishment of any state that excluded voters on the basis of race but not on the basis of sex. The amendment also introduced the word male into the Constitution when it referred to a citizen’s right to vote. Stanton predicted that “if that word ‘male’ be inserted, it will take us a century at least to get it out.”

Tennessee approved the Fourteenth Amendment in July, and Congress promptly welcomed the state’s representatives and senators back. Had President Johnson counseled other southern states to ratify this relatively mild amendment, they might have listened. Instead, Johnson advised Southerners to reject the Fourteenth Amendment and to rely on him to trounce the Republicans in the fall congressional elections.

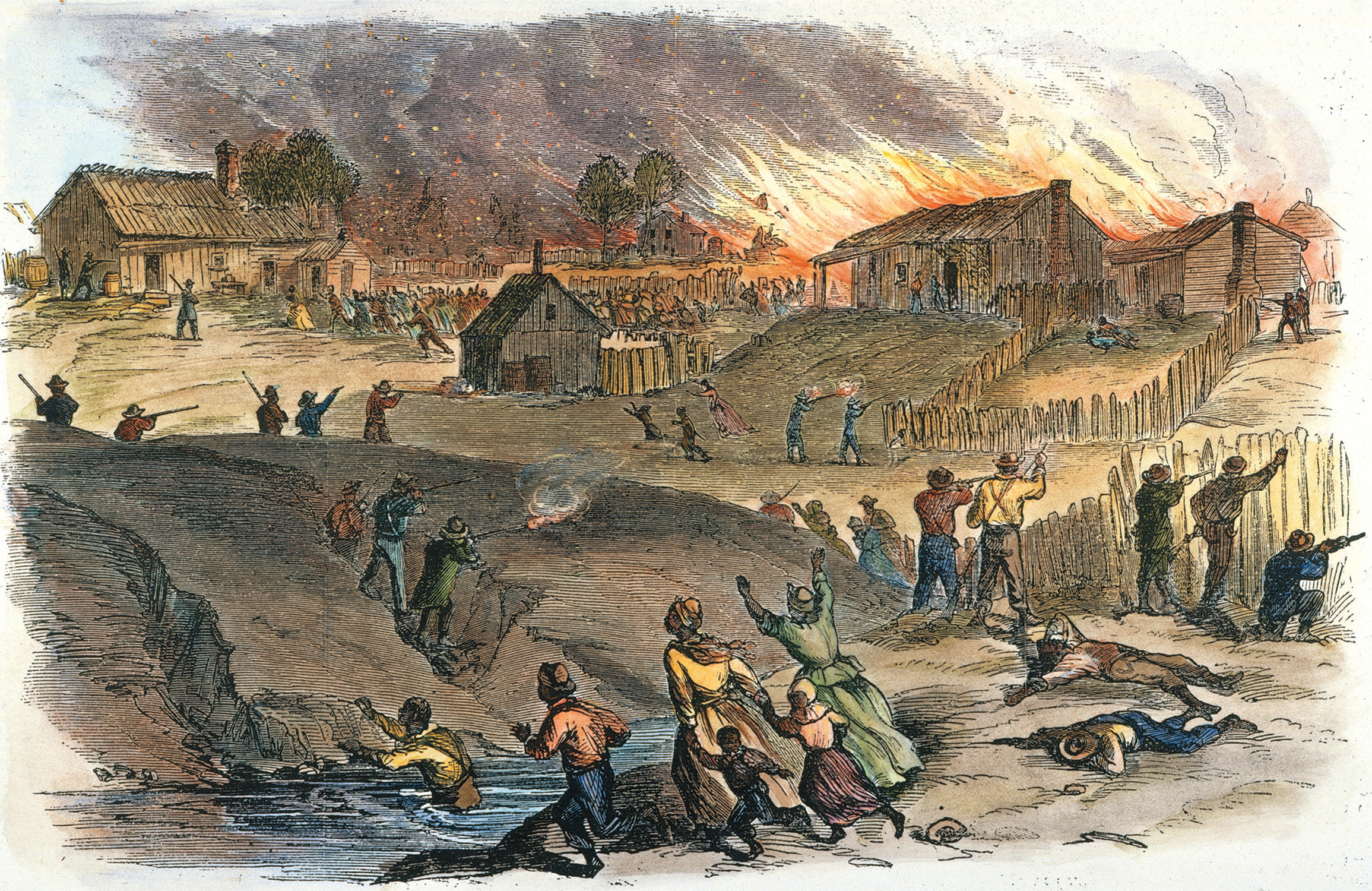

Johnson had decided to make the Fourteenth Amendment the overriding issue of the 1866 elections and to gather its white opponents into a new conservative party, the National Union Party. The president’s strategy suffered a setback when whites in several southern cities went on rampages against blacks. Mobs killed thirty-

The 1866 elections resulted in an overwhelming Republican victory. Johnson had bet that Northerners would not support federal protection of black rights and that a racist backlash would blast the Republican Party. But the war was still fresh in northern minds, and as one Republican explained, southern whites “with all their intelligence were traitors, the blacks with all their ignorance were loyal.”