The American Promise:

Printed Page 455

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 433

Chapter Chronology

Grant’s Troubled Presidency

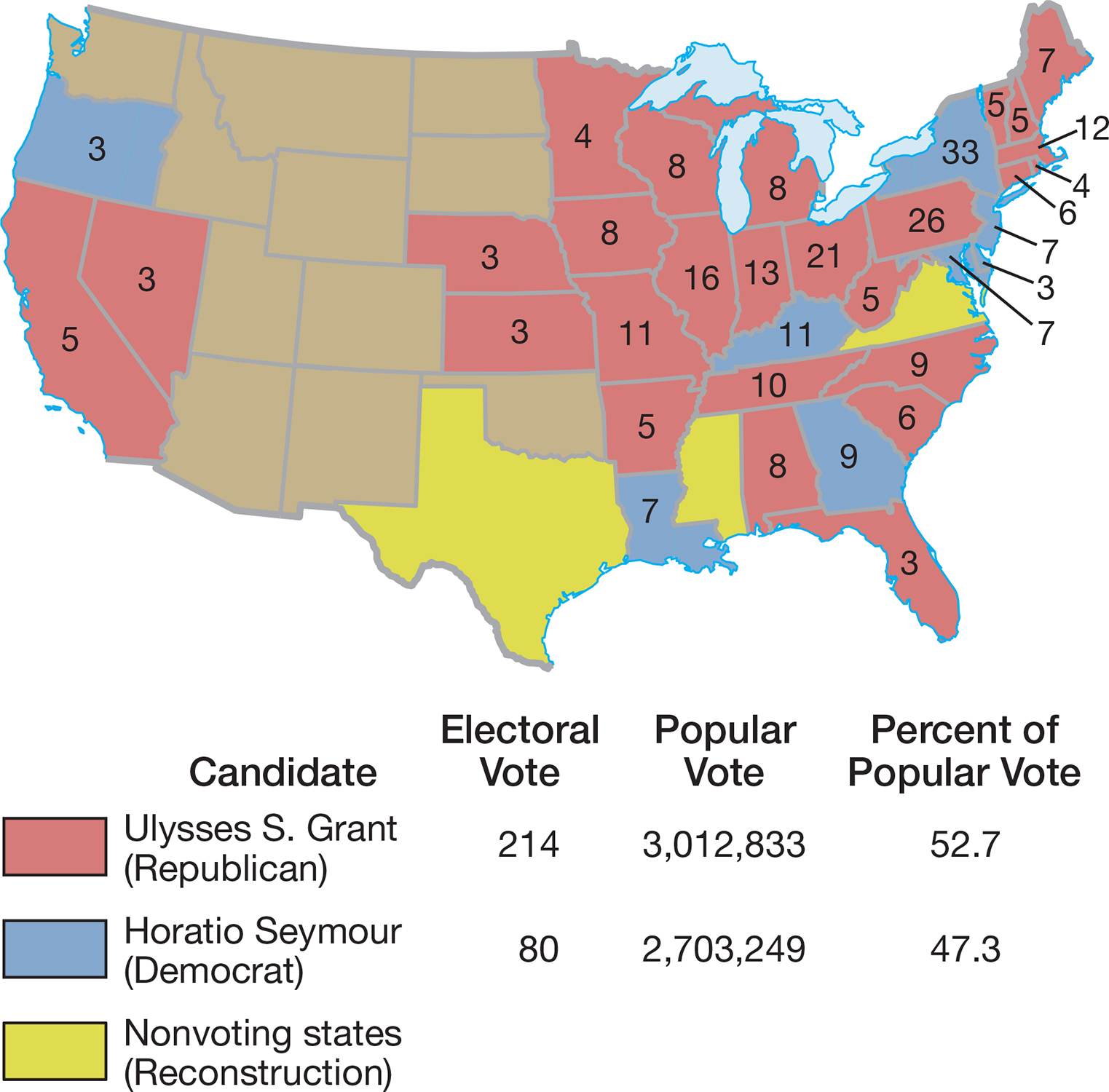

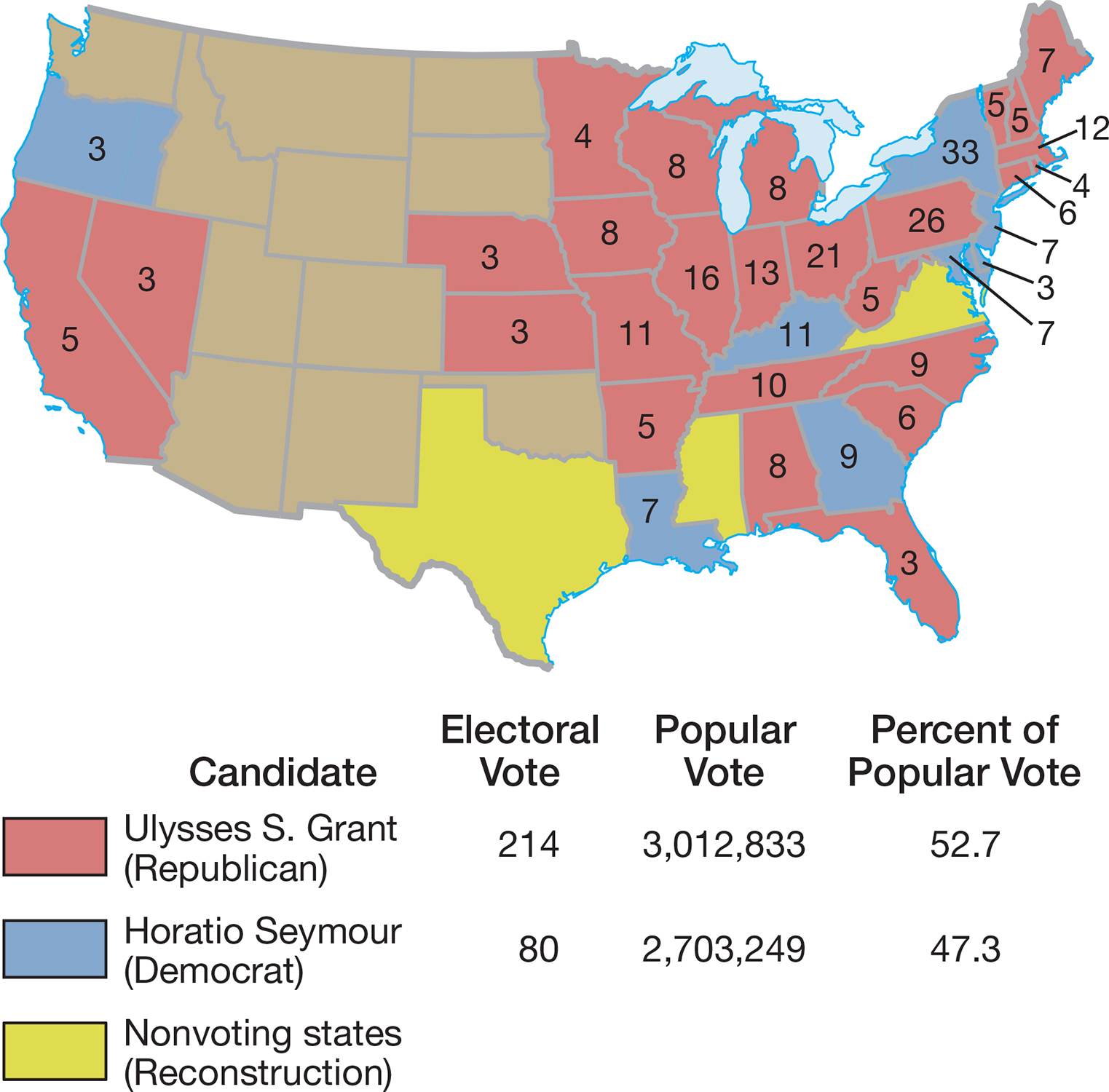

MAP 16.2 The Election of 1868

In 1868, the Republican Party’s presidential nomination went to Ulysses S. Grant, the North’s favorite general. His Democratic opponent, Horatio Seymour of New York, ran on a platform that blasted reconstruction as “a flagrant usurpation of power . . . unconstitutional, revolutionary, and void.” The Republicans answered by “waving the bloody shirt”—that is, they reminded voters that the Democrats were “the party of rebellion.” Despite a reign of terror in the South, costing hundreds of Republicans their lives, Grant gained a narrow 309,000-vote margin in the popular vote and a substantial victory (214 votes to 80) in the electoral college (Map 16.2).

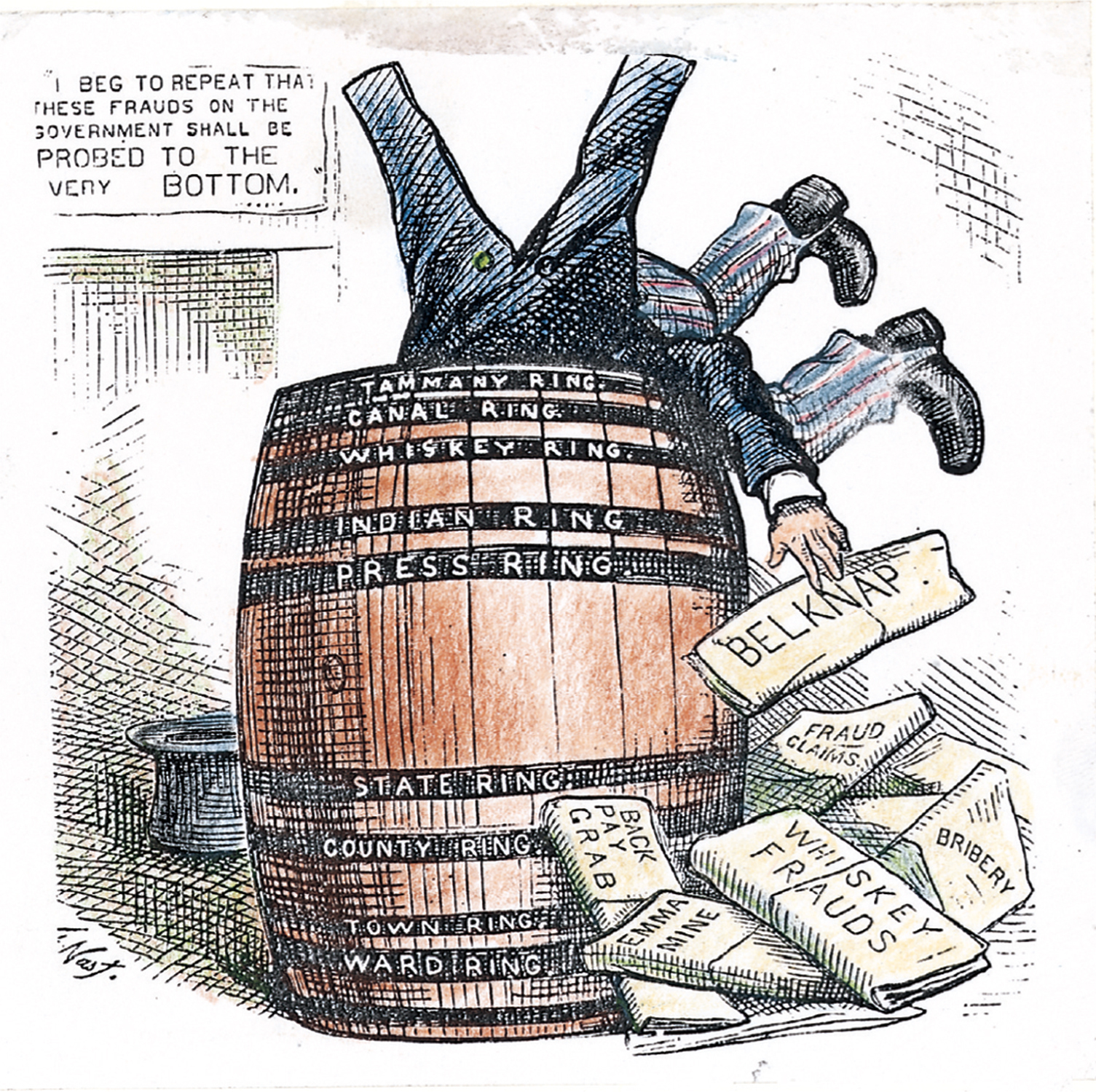

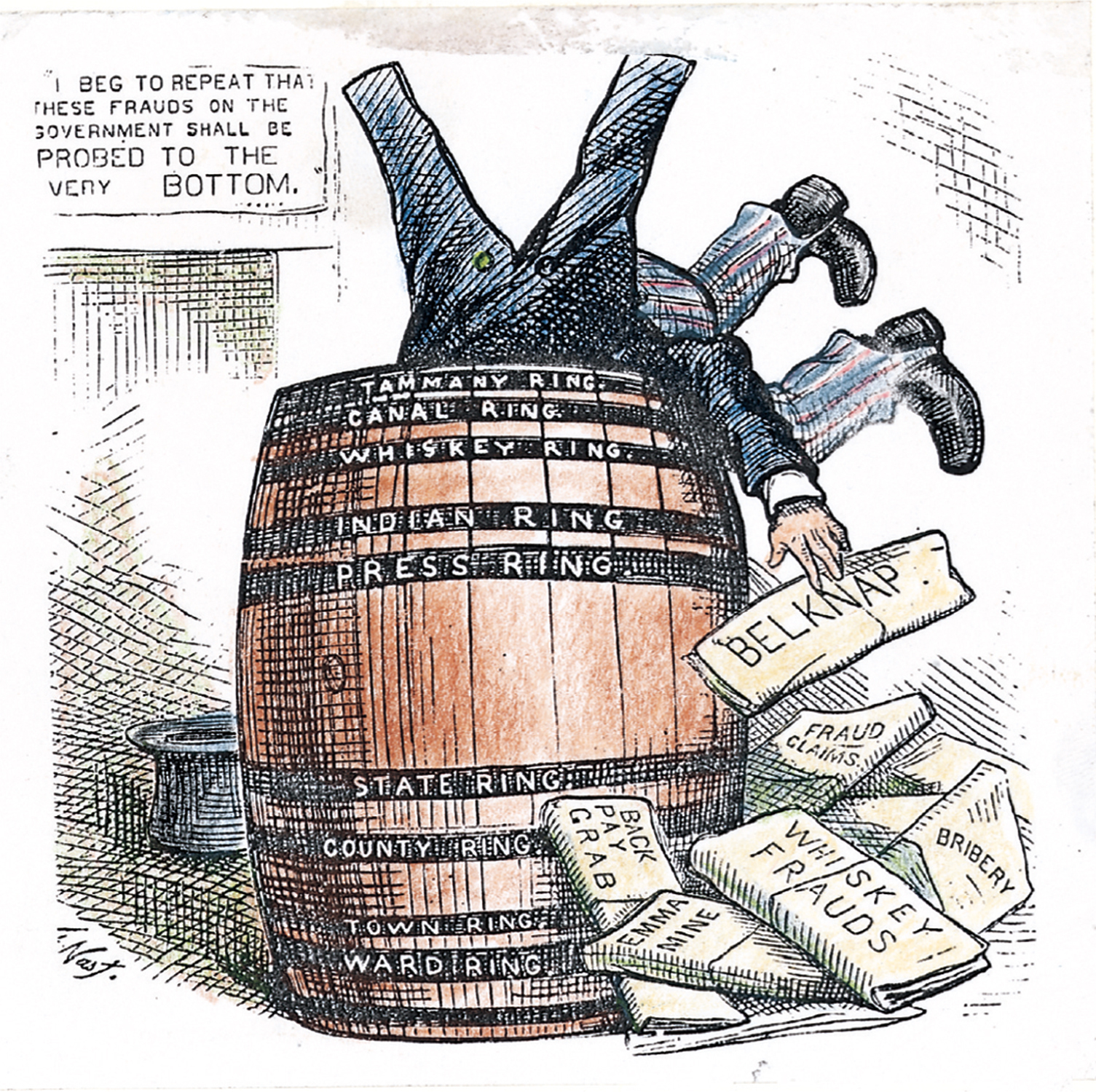

VISUAL ACTIVITY Grant and Scandal This anti-Grant cartoon by Thomas Nast, the nation’s most celebrated political cartoonist, shows the president falling headfirst into the barrel of fraud and corruption that tainted his administration. During Grant’s eight years in the White House, many members of his administration failed him. Sometimes duped, sometimes merely loyal, Grant stubbornly defended wrongdoers, even to the point of perjuring himself to keep an aide out of jail. Picture Research Consultants & Archives. READING THE IMAGE: How does Thomas Nast portray President Grant’s role in corruption? According to this cartoon, what caused the problems? CONNECTIONS: How responsible was President Grant for the corruption that plagued his administration?

Grant was not as good a president as he was a general. The talents he had demonstrated on the battlefield—decisiveness, clarity, and resolution—were less obvious in the White House. Grant sought both justice for blacks and sectional reconciliation. But he surrounded himself with fumbling kinfolk and old friends from his army days and made a string of dubious appointments that led to a series of damaging scandals. Charges of corruption tainted his vice president, Schuyler Colfax, and brought down two of his cabinet officers. Though never personally implicated in any scandal, Grant was aggravatingly naive and blind to the rot that filled his administration. Republican congressman James A. Garfield declared: “His imperturbability is amazing. I am in doubt whether to call it greatness or stupidity.”

In 1872, anti-Grant Republicans bolted and launched the Liberal Party. To clean up the graft and corruption, Liberals proposed ending the spoils system, by which victorious parties rewarded loyal workers with public office, and replacing it with a nonpartisan civil service commission that would oversee competitive examinations for appointment to office (as discussed in chapter 18). Liberals also demanded that the federal government remove its troops from the South and restore “home rule” (southern white control). Democrats liked the Liberals’ southern policy and endorsed the Liberal presidential candidate, Horace Greeley, the longtime editor of the New York Tribune. The nation, however, still felt enormous affection for the man who had saved the Union and reelected Grant with 56 percent of the popular vote.