The American Promise:

Printed Page 463

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 442

Introduction for Chapter 17

17

The Contested West

1865–1900

CONTENT LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain federal policies toward Native Americans during the last decades of the nineteenth century. Describe how Native Americans resisted these policies and how the government quashed these acts of resistance.

- Recount how the late-

nineteenth- century frenzy for gold and silver in the West transformed the region and explain how the development of the western mining industry mirrored the processes of industrialization in other parts of the country. - Identify who worked and settled in the West and why they were drawn there.

- Describe the ways in which farming became increasingly commercialized and ranching became increasingly industrialized.

TO CELEBRATE THE 400TH ANNIVERSARY OF COLUMBUS’S VOYAGE to the New World, Chicago hosted the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, creating a magical White City on the shores of Lake Michigan. Among the organizations vying to hold meetings at the fair was the American Historical Association, whose members gathered on a warm July evening to hear Frederick Jackson Turner deliver his landmark essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” Turner began by noting that the 1890 census no longer discerned a clear frontier line. His tone was elegiac: “The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of settlement westward,” he observed, “explained American development.”

Of course, west has always been a comparative term in American history. Until the gold rush focused attention on California, the West for settlers lay beyond the Appalachians. But by the second half of the nineteenth century, the West stretched from Canada to Mexico, from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean.

Turner, who originally studied the old frontier east of the Mississippi, viewed the West as a process as much as a place. The availability of land provided a “safety valve,” releasing social tensions and providing opportunities for social mobility that worked to Americanize Americans. Turner’s West demanded strength and nerve, fostered invention and adaptation, and produced self-

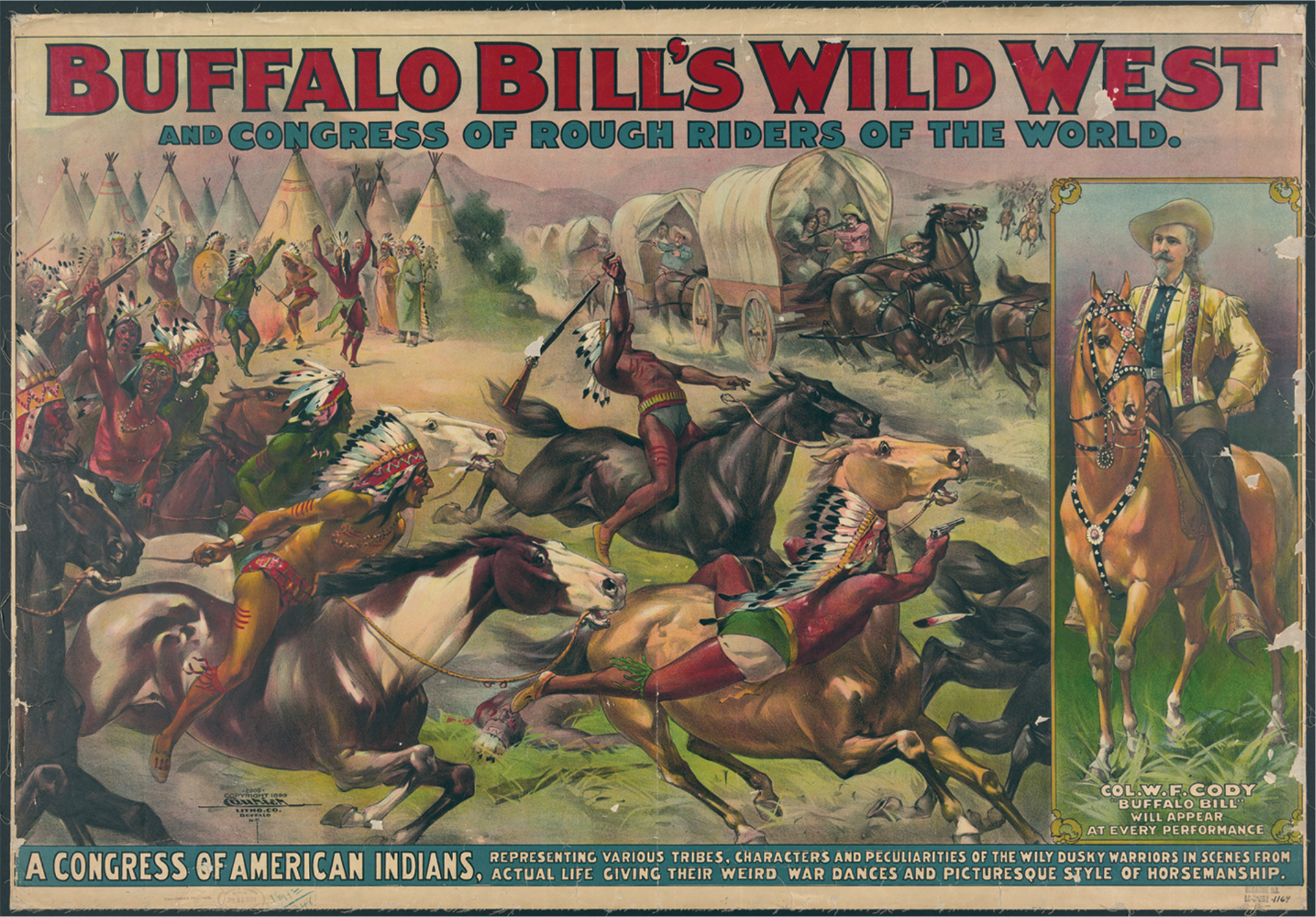

Yet the historians who applauded Turner in Chicago had short memories. That afternoon, many had crossed the midway to attend Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West extravaganza—

In the decades following the Civil War, the United States pursued empire in the American West in Indian wars that lasted until 1890. Pushed off their land and onto reservations, Native Americans resisted as they faced waves of miners and settlers as well as the degradation of the environment by railroads, mines, barbed wire, and mechanized agriculture. The pastoral agrarianism Turner celebrated in his frontier thesis clashed with the urban, industrial West emerging on the Comstock Lode in Nevada and in the commercial farms of California.

Buffalo Bill’s mythic West, with its heroic cowboys and noble savages, also obscured the complex reality of the West as a fiercely contested terrain. Competing groups of Anglos, Hispanics, former slaves, Chinese, and a host of others arrived seeking the promise of land and riches, while the Indians struggled to preserve their cultural identities. Turner’s rugged white “frontierman” masked racial diversity and failed to acknowledge the role of women in community building.

Yet in the waning decade of the nineteenth century, as history blurred with nostalgia, Turner’s evocation of the frontier as a crucible for American identity hit a nerve in a population facing rapid changes. A major depression started even before the Columbian Exposition opened its doors. Americans worried about the economy, immigration, and urban industrialism found in Turner’s message a new cause for concern. Would America continue to be America now that the frontier was closed? Were the problems confronting the United States at the turn of the twentieth century—

CHRONOLOGY

| 1851 |

|

| 1862 |

|

| 1864 |

|

| 1867 |

|

| 1868 |

|

| 1869 |

|

| 1870s |

|

| 1873 |

|

| 1874 |

|

| 1876 |

|

| 1877 |

|

| 1879 |

|

| 1881 |

|

| 1882 |

|

| 1886 |

|

| 1886– |

|

| 1887 |

|

| 1889 |

|

| 1890 |

|

| 1893 |

|