The American Promise:

Printed Page 637

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 598

The Red Scare

Suppression of labor strikes was one response to the widespread fear of internal subversion that swept the nation in 1919. The Red scare (“Red” referred to the color of the Bolshevik flag) exceeded even the assault on civil liberties during the war. It had homegrown causes: the postwar recession, labor unrest, terrorist acts, and the difficulties of reintegrating millions of returning veterans. But unsettling events abroad also added to Americans’ anxieties.

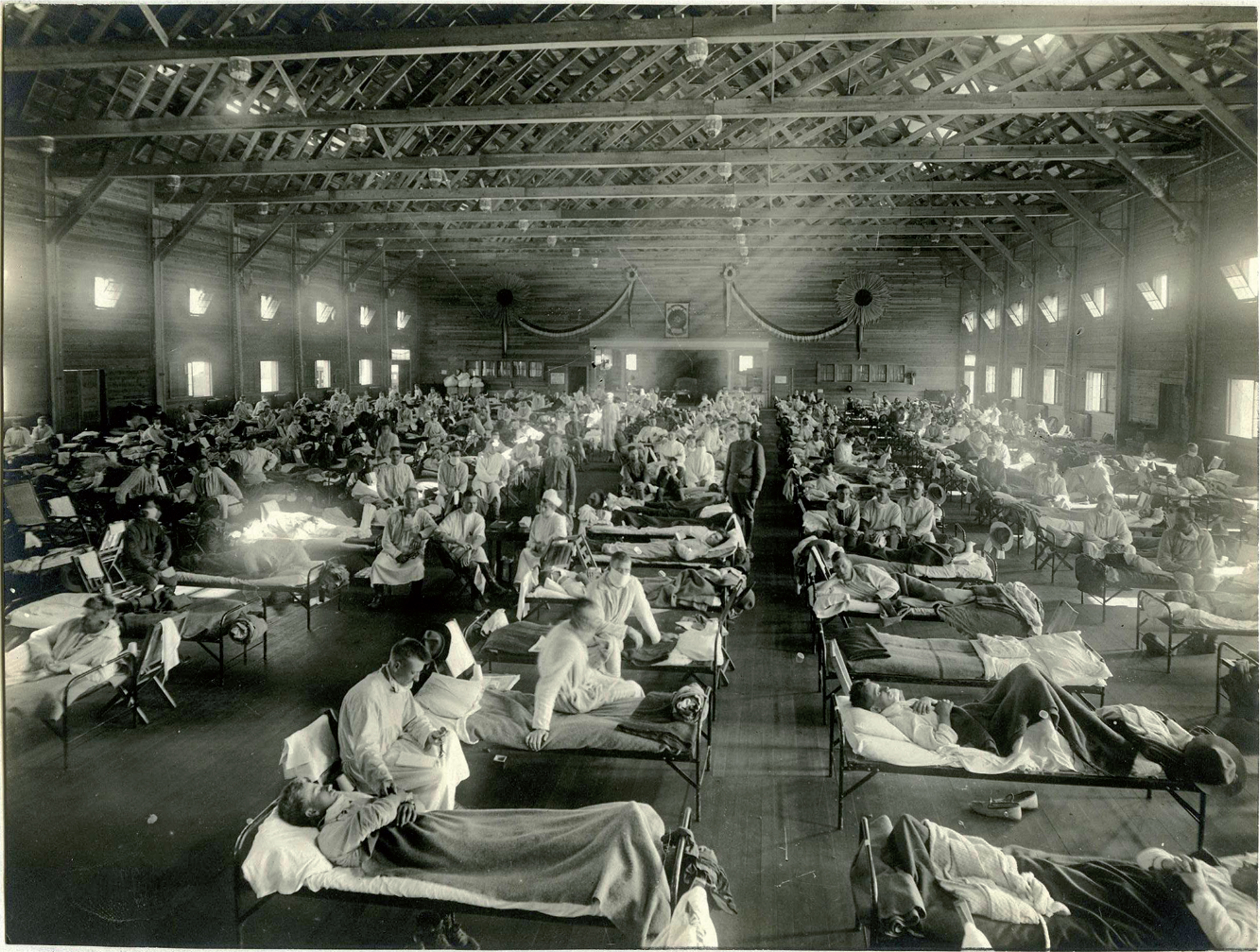

Two epidemics swept the globe in 1918. One was Spanish influenza, which brought on a lethal accumulation of fluid in the lungs. A nurse near the front lines in France observed that victims “run a high temperature, so high that we can’t believe it’s true. . . .

The other epidemic was Russian bolshevism, which seemed to most Americans equally contagious and deadly. Bolshevism became even more menacing in March 1919, when the new Soviet leaders created the Comintern, a world-

Even before the Wall Street bombing, the government had initiated a hunt for domestic revolutionaries. Led by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, who believed that “there could be no nice distinctions drawn between the theoretical ideals of the radicals and their actual violations of our national laws,” the campaign targeted men and women for their ideas, not their illegal acts. In January 1920, Palmer ordered a series of raids that netted 6,000 alleged subversives. Finding no revolutionary conspiracies, Palmer nevertheless ordered 500 noncitizen suspects deported.

His action came in the wake of a campaign against the most notorious radical alien, Russian-

The effort to rid the country of alien radicals was matched by efforts to crush troublesome citizens. Law enforcement officials and vigilante groups joined hands against so-

Public institutions joined the attack on civil liberties. Local libraries removed dissenting books. Schools fired unorthodox teachers. Police shut down radical newspapers. State legisla-

That same year, the Supreme Court provided a formula for restricting free speech. In upholding the conviction of socialist Charles Schenck for publishing a pamphlet urging resistance to the draft during wartime (Schenck v. United States), the Court established a “clear and present danger” test. Such utterances as Schenck’s during a time of national peril, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote, were equivalent to shouting “Fire!” in a crowded theater.

In 1920, the assault on civil liberties provoked the creation of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which was dedicated to defending an individual’s constitutional rights. One of the ACLU’s founders, Roger Baldwin, declared, “So long as we have enough people in this country willing to fight for their rights, we’ll be called a democracy.” The ACLU championed the targets of Attorney General Palmer’s campaign—

The Red scare eventually collapsed because of its excesses. In particular, the antiradical campaign lost credibility after Palmer warned that radicals were planning to celebrate the Bolshevik Revolution with a nationwide wave of violence on May 1, 1920. Officials called out state militias, mobilized bomb squads, and even placed machine-